Bank Failure and Predictors of Performance

The Federal Reserve Bank of New York published three articles on why banks fail (the first one here). While the aim of the research was to identify the cause of approximately 5,000 US bank failures over the course of 160 years, the research also infers what factors bank executes can influence to not only avoid failure but to improve performance. In summary, the research finds that bank failure is caused primarily by rapid asset growth, that then causes rising asset losses, deteriorating solvency, and an increasing reliance on expensive non-core funding. The immediate and visible cause of bank failure is one of two reasons: bank runs (rapid deposit withdrawals) or poor fundamentals (credit risk, interest rate risk, or fraud). We will focus on how this research can help community bankers make decisions today to avoid business mistakes and achieve higher performance for their institution.

Dynamics of Bank Failure and Performance

Credit Risk: While the study spans 160 years, it divides the analysis between pre- and post-FDIC periods (the latter between 1959 and 2023). We will consider post-FDIC failures only. The study shows that bank failure can be predicted by a rise in non-performing loans/loans (NPL), which leads to loan loss provisions, decreasing income and decreasing equity ratio. However, net interest margins (NIM) are stable. The graph below shows capitalization, net income, NIM and NPL for failing banks in quarters before failure.

The key lesson for community bank executives is to use risk-adjusted, return-on-asset (RAROC) pricing tools to compensate community banks for credit and interest rate risk. While any measurable risk can be compensated with higher yield, the practical outcome of applying RAROC tools for community banks is that banks lose higher risk loans to banks that do not use RAROC tools – a positive outcome for a bank. Credit ratings or buckets are not sufficient risk measuring tools for community banks, and managers must migrate to predictive (especially AI-aided) probability of defaults, loss-given defaults, and exposure at default RAROC tools. It is worth noting that NIM remains stable to failure. We believe this reflects management decision to increase asset yield as cost of funding increases.

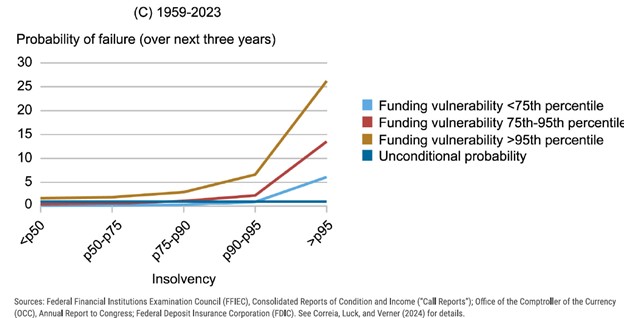

Funding Risk: Failing banks increasingly rely on noncore funding. This includes large, uninsured time deposits and wholesale funding. These deposits are more expensive than core funding and are more sensitive to movements in interest rates (creating more interest rate risk). The graph below shows probability of bank failure over the next three years as measured by bank insolvency and funding vulnerability. It shows that reliance on more expensive and risk-sensitive noncore funding increases the risk of bank failure. The top 5 percentile of funding vulnerable banks (the line in gold) are especially more likely to fail.

The key lesson for community bank executives is to use shareholder value added analysis that measures a bank’s return over its cost of capital to assess if scale is helping maximize long-term shareholder return versus just adding size and scale. Adding size and scale on assets that earn below a banks cost of capital (approximately 12.5% hurdle), hurts a bank’s long-term performance. Further, community bank executives should incorporate fund funds transfer pricing tools to measure profitability where duration and liquidity mismatches exist between assets and liabilities. As identified in the study, NIM is not predictive of failure, and it is not the right sole measure to gauge long-term profitability. We believe that targeting asset yield to maximize NIM, is a factor in community bank underperformance.

Conclusion For Community Banks

The ultimate cause of bank failures and bank crises is most often deterioration of bank solvency. The cause of deteriorating bank solvency is typically gradual, taking place over several years or even decades. During those years, banks accumulate unaccounted and unmeasured credit risk that erodes capital buffers. The banks that fail take more risk during boom periods than their peers – most often without the tools required to measure that risk/return tradeoff. Depositors and regulators tend to be slow to react to this change in bank fundamentals. Intervention by bank executives, in the form of more sophisticated risk/return tools, is a requisite for better long-term bank performance.