Use This 5S Framework for Solving Strategic Challenges in Banking – Part I

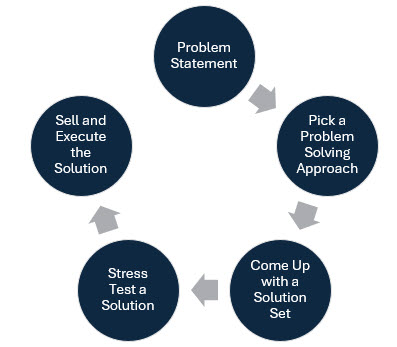

Banks face a big set of challenges ahead. To gain a competitive advantage, having an effective and efficient systematic approach that is repeatable and can be part of your bank’s culture would be helpful. In this article, we provide a five-step AI-enabled process that will help your bank with solving strategic challenges.

5S Framework Overview for Solving Strategic Challenges

The “4S” problem-solving framework is largely attributed to authors Garrette, Phelps, and Sibony in the top-selling book Cracked It (worth a read in itself) and then made famous by McKinsey & Company. We have adapted it for banking and the modern AI era and present the framework in the following steps: State, Structure, Solve, Stress Test, and Sell.

Step 1: State — Understanding Your Problem Statement to the CORE

It is common for bankers to solve a half-articulated problem. “Improve earnings” is a frequent problem statement that is unclear and not precise. Vague problem statements show that you don’t understand or care enough to explain the problem. Either is an issue when it comes to solving strategic challenges in banking.

Bankers are problem solvers, so when presented with a half-thought-out problem, they will quickly jump to a possible solution that may or may not solve the true problem. For bankers, ask them to “improve earnings,” and many will jump to “increase loan growth” without realizing that the solution might be the last thing a bank needs. Generating profitable loans, increasing fee income, lowering deposit costs, or reducing operating costs might all be better alternatives to growing loan originations.

“If I had an hour to solve a problem, I’d spend 55 minutes thinking about the problem and 5 minutes thinking about solutions.” — Albert Einstein.

Bankers can use the “CORE” framework to help understand a problem. CORE represents the fundamental elements of decision-making and problem-solving. By answering these questions, bankers can get to the “core” of an issue.

Cause: What are the underlying root causes of this problem?

Owners: Who owns or should own this problem? Who is going to be concerned with how this problem is solved (i.e., what other departments or units need to be part of the solution)?

Results: How will you know when the problem is solved? What are the best metrics to use?

Edges: What are the boundaries of the problem now and in the future? What inputs do we have to consider when solving the problem? What are our constraints as to the risk, cost, talent, time, data, technology, regulation, and preexisting commitments? Here, we highlight that it is important to understand the edges of the problem now but also how these constraints will change in the future. Will capital, for instance, become more expensive or cheaper? Are there available technologies that could help solve this problem by implementing them? Too often, bankers try to solve problems based on their past experience, which may or may not be valid to solve this problem going forward.

Once the above data is collected, a more effective problem statement can be formed. This helps better execute when going about solving strategic challenges. For example, the problem of “improving earnings” becomes:

Rank the most effective way for the bank to increase profit by 20% within the next 2 years while increasing risk by only 10% and holding capital constant.

Note that the way this question is posed forces bankers to think of multiple options and present them in ranked order. It considers both reward and risk, underlining the fact that there is no free lunch. For the sake of brevity, we have simplified this question. Still, banks can enhance this problem statement by focusing on other dimensions such as departments (deposits, loans, fee income, etc.), products (treasury management, commercial loans, etc.), or geography.

Step 2: Structure — Choosing a Problem-Solving Approach When Solving Strategic Challenges

Different problems lend themselves to various forms of solutions. It may be too soon in the process to even come up with a problem statement, or the problem may not have a knowable solution yet. For example, you might be looking for a completely new branch model – one that has not been invented yet. This would lend itself to more of an issue-driven or, more likely, a design-thinking approach.

Getting the structure of the approach right not only enhances the quality of the solution but can save days of work.

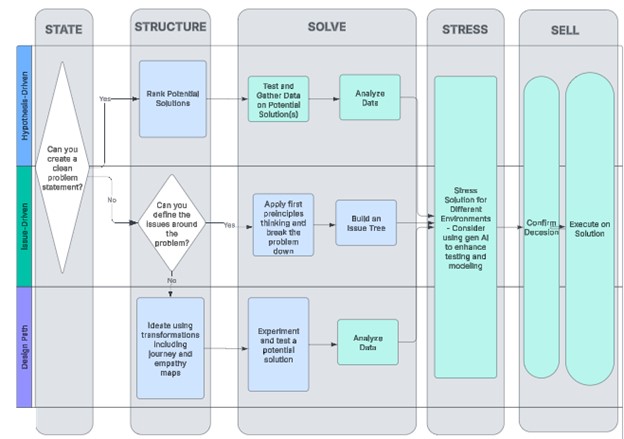

Banks generally use one of three problem-solving approaches.

The Hypothesis-Driven Path

If the problem is understood, data can be collected and the solution can be tested with some agreed upon metrics for success, then the hypothesis-driven path is likely the most applicable. This path is also the most common and straightforward.

When coming up with various solutions, each solution needs to be mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. That means the solutions are distinct and discernible and the solution solves the entire problem and not part of the problem. If you cannot derive a single solution that is distinct and exhaustive, then a different approach is needed.

Luckily, most banking problems can be stated, and a variety of solutions that are exclusive and exhaustive can be derived.

The next step is to figure out how to test the solutions. Bankers usually debate the solutions and then rank the ones they most believe in. At this point, attempting to test a solution is most helpful. This might involve going hands-on with a piece of technology, conducting a customer survey, using a test market, or gathering other opinions within and external to the bank.

The data is analyzed on the test market, and a path is decided on. Either the tested solution meets the problem’s criteria, or a restructuring of the solution is needed. If a solution meets the success criteria, it is finally stressed and tested by either “red teaming,” modeling, or further examination.

Stress testing allows a cross-functional assessment to confirm whether the solution fits within the risk envelope, is a feasible solution at scale and solves the problem for both the short and long term. Stress testing is where interdependencies are explored to better understand how the solution fits into a long-term strategy and tactical plan.

For example, a particular vendor may provide a digital account opening solution for retail and commercial customers. The bank would then test the solution by going hands-on and talking to other banks that use the product. If the product seems to pass the test, then it is within stress testing that the team understands whether the platform can be used for loan origination, account maintenance, and whether the platform can adapt to new products in the future. Stress testing forces the bank to take a broader and longer-term view of the solution.

Issue-Driven Solutioning

If there is no clear solution, bankers often build an “issue tree.” In cases where a clear problem statement cannot be articulated, the next choice is to approach a problem from an issue-driven methodology. Issue-driven solutioning is like a hypothesis-driven path but the solution space is larger to include challenging the underlying assumptions of the problem. This approach is also suited for when you don’t like any of the apparent solutions and need to think deeper about the problem.

An issue tree breaks the problem down into smaller, first-principles pieces so you get to the most fundamental truths about a problem. Here, you start asking questions about the issue.

- What are our core assumptions about the problem?

- Are those assumptions valid going forward (given digital, AI, changing demographics, etc.)

- What data do we need to arrive at a solution?

- If we had no constraints, what would be our solution?

For example, for the problem – Rank the most effective way for the bank to increase profit by 20% within the next 2 years while increasing risk by only 10% and holding capital constant – we might build the following issue tree:

While the hypothesis path often produces multiple solutions, the Issue-driven approach often just produces a limited number of solutions, if not just one.

For true open-ended problems where there is nothing close to a clear solution, we turn to “design thinking.”

Design Thinking Methodology

When solving strategic challenges, design thinking is best used when you don’t fully understand the problem. Design thinking gained popularity with Apple when they used it to reinvent the cell phone.

Design thinking is an iterative approach aimed at understanding users, challenging assumptions, redefining problems, and creating innovative solutions for prototyping and testing. The primary objective is to uncover novel solutions that may not be immediately obvious. Design thinking goes beyond just a process; it fosters a new way of thinking and offers practical methods to apply this mindset effectively.

Design thinking starts with “empathizing” with the end user, whether an employee or a customer. This is a radically different methodology than the previous two problem-solving methodologies. This makes design thinking especially suited for solving problems with a user interface, workflow, or bank-to-client interaction.

Empathizing with the user means not just asking what the user really wants to accomplish. To the adage – Do they need a 1 5/8ths drill bit, a 1 5/8ths hole, or do they need a door lock installed? The clarity here is that you want to make sure you are solving the right problem.

The classic Harvard case study of the slower elevator problem is an iconic example of design thinking. The problem statement started out as “the office elevators are too slow.” The hypothesis-driven and issue tree path came up with the solution set – install an additional elevator, upgrade the elevator motors, and improve the algorithm of where the elevators wait. With design thinking, it was uncovered that the real problem was “annoying wait times.” This led to a different solution, which included putting up mirrors, playing music/videos, and installing hand sanitizer to occupy the time. Instead of the cost of a faster elevator, the solution set was an inexpensive “make the wait feel shorter” outcome.

Often, it is helpful to brainstorm the problem and transform it into graphics, mind maps, or storyboards to turn it around and look at it from different perspectives.

Next, you Build, Measure, Learn, and test potential solutions. This is where banks can experiment with pilot programs and prototype solutions that solve part or all of the problem.

Next Up – Part II in Solving Strategic Challenges

Solving strategic challenges using the 5s methodology belongs at every level of banking, from the teller down to the CEO. We tackled the importance of understanding the problem and presented three different methodologies for solving the problem. Next week, we will finish off the series and cover the remaining three “S” s – solving, stressing and selling the solution.