You Need to Understand These Reasons for Bank Consolidation

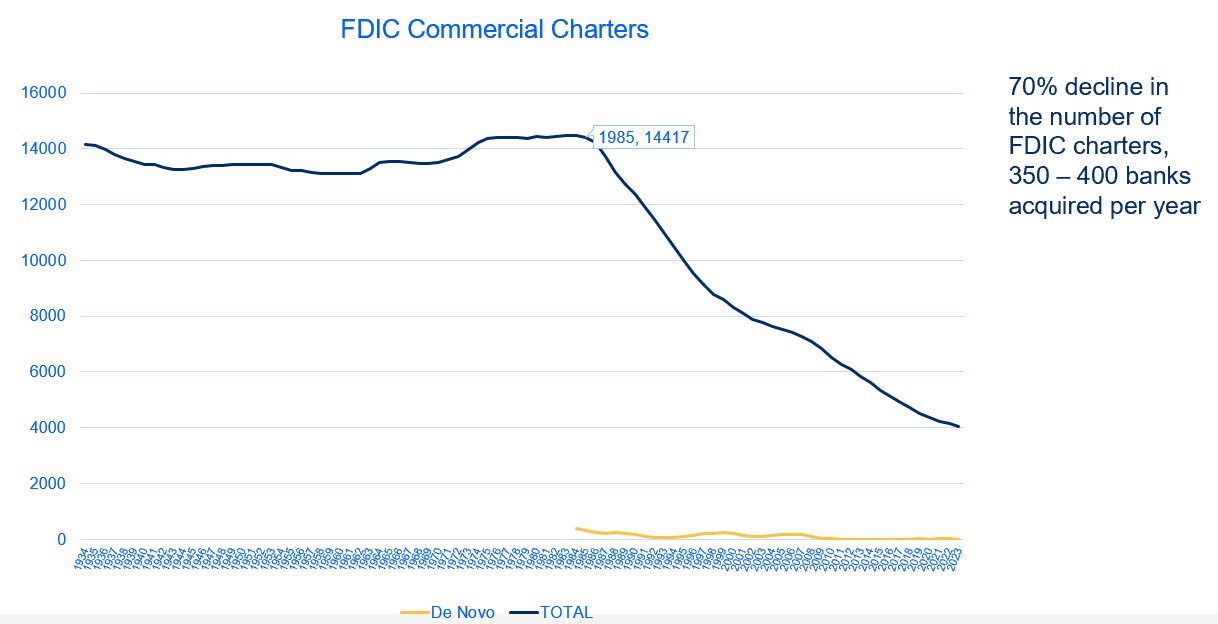

By 1985, the banking industry had radically changed. Consolidation among financial institutions started to occur at a pace never seen before, a pace that continues to this day. Understanding the drivers of banking consolidation is imperative when managing bank performance. In this article, we break down the lessons from this long-term trend.

In 1985, there were 14,417 FDIC banking charters. Today, in 2025, we are down to 4,496. The question is, what changed in 1985 that precipitated this downward trend?

Deregulation, economic conditions, and competitive pressures drove the wave of bank consolidation that began in 1985. Let’s break it down and relate these trends to today’s environment.

The Impact of Regulatory Changes on Bank Consolidation

The largest impacts during the eighties were the two major regulatory acts creating more deposit competition.

- The Depository Institutions Deregulation and Monetary Control Act of 1980 phased out interest rate caps on deposits, making competition more intense.

- The Garn-St. Germain Depository Institutions Act of 1982 enabled thrifts to offer money market accounts and expand lending powers, fostering competition with banks. The Act also allowed bank holding companies to acquire failed banks across state lines.

These two acts took the governors off around how banks managed deposits. These acts created a competitive vortex marking a paradigm shift around the concept of bank management. Prior to 1980, financial stability was paramount. With deregulation in 1980, innovation and efficiency were now held in the highest regard.

Unfortunately, many banks were not equipped to manage deposit volatility as they got in a rate war for money market accounts and Super Now accounts. Banks struggled to control their cost of funds because they did not understand their business model.

For the 39 years between 1940 and 1979, there were only 246 bank failures and $134mm in deposit insurance losses. For the 9 years from 1980 to 1989, there were 1,086 bank failures and $23B in deposit insurance losses.

The two acts above also contributed to the rise of interstate branch banking. Banking across state lines and the Douglas amendment to the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 forbid holding companies from acquiring banks outside the state where the holding company was headquartered unless the state of the bank being acquired explicitly allowed for these types of acquisitions. No state allowed this until 1978. Many states restricted geographical branch expansion within the state.

By 1982, several states in the South started to allow branch banking within their state. In 1984, the OCC allowed federally chartered banks to expand within a state if the state allowed it. During the mid-1980s, “unit banking,” or having a single bank location, was no longer a restriction in some states, and banking flourished. By 1994, the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act repealed unit banking restrictions at the Federal level.

Banks were now allowed to operate across state lines, increasing competition. Interestingly, many bank management teams failed to adapt to competition, not taking advantage of profitable geographies or products. These banks were further driven into the hands of competitors.

The Role of Economic Pressures

The late 1970’s was marked by a period of high inflation. As the caps came off deposit rates, banks increased their rates offered to retail and commercial customers. In 1980, the ceiling rate on savings deposits was 5.50%. Treasury bills in comparison, were approximately 11.5% and money market mutual funds were 13% or greater. Money poured into these accounts, hurting banks.

With deregulation and against a backdrop of increasing bank failures, the FDIC deposit insurance was raised from $40,000 to $100,000, and the ceiling savings rate was phased out. In response, banks routinely paid 8% for savings accounts, stemming the outflow of funds.

At the same time, starting in 1984, regulators started recording the CD rates at banks for public consumption. This tipped off additional competition, as banks now knew the rates at their fellow banks and could post above them. Banks started to compete for term deposits, not understanding that they were cannibalizing their own checking and savings rates.

In 1980, savings, money market accounts, and non-jumbo CDs comprised 41% of a bank’s deposits. By 1985, this number jumped to 51%.

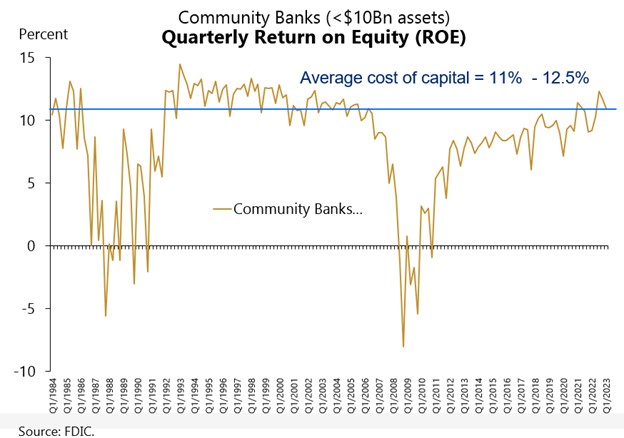

As seen below, many banks and thrifts failed to manage their asset-liability and credit positions and chronically produced under their cost of capital. The Savings and Loan Crisis ensued, prompting mergers and acquisitions as healthier banks absorbed struggling ones.

The Role of Technological Advances in Bank Consolidation

A third major influence that drove bank consolidation starting in the 1980s was a change in bank technology. Automated teller machines started to take hold, and the Electronic Funds Act of 1978 phased in a set of protocols that made ACH, point-of-sale systems, ATMs, electronic withdrawals, and debit card transactions more feasible.

Remote banking programs, telephone banking and greater ATM usage were a result. At the same time, the rise of the personal computer started to allow for dial-up banking. As the Internet became popular in the 1990’s, large banks rolled out online banking in the late 90’s continuing to fuel competition. This trend continued through the late 2000s with the gain in popularity of mobile banking.

The Role of Business Model in Bank Consolidation

As banks consolidated, in times of low credit risk, large banks outperformed smaller banks due to their economies of scale, which improved efficiency, driving profitability.

The 1980s saw increased competition from non-banks, such as mutual funds and brokerage firms that have since given way to fintechs and neobanks. The 1980s also saw an influx of foreign banks entering the US market, targeting commercial customers. In the 1980’s, Japanese banks, with offices in the US, accounted for 2.7% of C&I lending. By 1988, this share increased to 8.5%. In addition to the Japanese, German, Swiss, and Canadian banks created greater competition that remains today. In 1980, all foreign-controlled banks composed about 13% of commercial lending. By 1988, the amount rose to 28%, and almost every major U.S. corporation had one or more foreign banks in their bank group.

Consolidation of Banking in the Future

Starting in the 1980s, deregulation ushered in the current wave of bank consolidation that we continue to experience. Banks have gotten better at managing interest rates and credit risk, hopefully dampening some of the consolidation effects in the future. However, in this current age of deregulation, the rise of crypto assets competing for deposits, and major technology shifts in data and artificial intelligence, look for consolidation to increase.

To stay competitive, banks must find ways to consistently produce a risk-adjusted return above their cost of capital. Focusing the organization on producing between 12% and 15% is a way to ensure your bank doesn’t get consolidated and has the option of being the consolidator.