Here is The Math Behind the High-Yield Account

There have been many a banker who has said they want to offer a high-yield account because the “higher interest expense is just like paying marketing costs.” This banker may even be thinking of starting a completely new digital bank using a high-yield account as its flagship product. The logic that “rate sells itself” is true. It is also true that the tactic is self-reinforcing as this banker will undoubtedly have success and be lauded for the balances they can build. However, is this the best move? In this article, we explore the tactic of a high-yield deposit account.

The Cost of New Customers

The reality is that opening a new account is expensive. Customers rarely walk into your branch or through digital doors, ready to move the business to you. Occasionally, due to geographic location, that happens. If you bank in a fast-growing state such as Nevada, Utah, Idaho, Arizona, Texas, Florida, or South Carolina, population and business formation growth result in lower acquisition costs.

However, the majority of customers require a referral, a marketing effort and a sales effort to bring them in the door. For a quality commercial customer, this acquisition, sales and marketing costs is around $14,000 spread over a 32-month sales cycle. If you have a unique brand, product, service or offering, this cost, and time, can be dramatically reduced.

A High-Yield Account Sells Itself

The old banking adage that the right rate sells itself is true. Offer a loan rate that is low enough or a deposit rate that is high enough, and your demand will go parabolic. Not everyone needs rewards points, instant payments, or weekend service, but everyone needs cheap capital and more income. If you were to offer a 6% CD promotion in the current market, like a handful of credit unions and fintechs currently do (HERE), marketing becomes close to free, sales costs drop to near-zero, and the sales cycle can be measured in hours, not years. This feels like a win, but it is most likely not. Like eating that extra dessert, it feels good going down, but the problem is you now have to live with baggage that comes with that dessert.

Looking at the Math of an Average Business Savings Account – Case Study

Let’s take one of the most underutilized products in banking: the business savings account. This account is rarely pushed by banks and often not even appropriately understood. While a topic for another time, many banks offer a business savings account, but then offer a higher rate money market account while also offering short-term CDs at a similar rate. The combination of competing products ends up driving up costs for the bank, while robbing the bank of product options all the while confusing the customer. If properly designed, your business savings account should have a duration and estimated life comperable to your transaction account offering, and larger than your money market offering.

Setting aside the product line up, let’s look at a case study. We will take a mature business in wholesale distribution that would be a target corporate customer of almost any bank. The business doesn’t have real estate to finance, and your branch and corporate team court them over from another bank with the lure of better service and a better relationship. They open a $60,000 transaction account and a debit and credit card but don’t need treasury services. Your banker smartly cross-sells them a savings account and pays them the current national average of 59 basis points. They put $40,000, which is the national average for this type of account, on deposit to save for an emergency capital expense, such as if they must replace a forklift or cargo van.

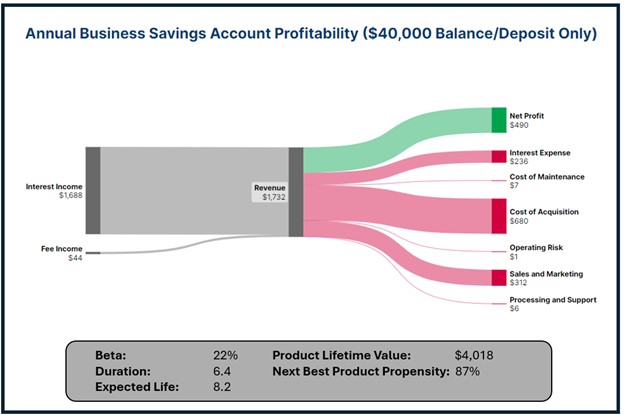

The economics look something like the below.

The attribution to interest income is impressive, but it is eaten up by the cost of acquisition, sales, and marketing expenses. Still, this account throws off approximately $490 of net profit. Not bad, but not great.

The Math of a High-Yield Business Savings Account

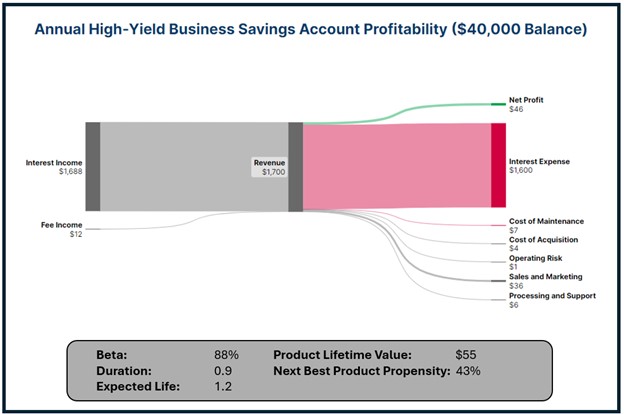

In contrast, a bank down the street wants to quickly raise deposits and acquire customers so they offer a 4% business savings account (currently offered by several banks in the market today). This bank’s average exception pricing is in the 5% area, so this seems like a good deal for the bank. They offer this high-yield savings account as a hook when you open a transaction account. Sure enough, money comes flooding in. The economics and performance metrics are below.

Now, if you are not tracking product or customer profitability, you are likely happy with the inflow of new accounts that you are getting by offering this high-yield account. It is also likely that you have some vague plan to reduce the rate on the account in the future and cross-sell this customer into other products.

Unfortunately, this is rarely the case.

For starters, and no surprise, paying a 4% rate eats up most of the bank’s profit here. While it is true that acquisition, sales, and marketing costs drop dramatically, there is a glaring problem in the analytics. This customer is highly rate sensitive (numerically a sensitivity or beta of 88%), which is why they were attracted to the offer in the first place. Because of this sensitivity, they will likely leave your bank when the next best offer comes around or you drop rates. The combination of the high interest rate offering and the high sensitivity means their expected life is short and their duration low.

Because of the high beta and short expected life, you need to amortize the acquisition, sales, and marketing costs quickly and have little time to cross-sell other products. Not only is product lifetime value clipped, but customer lifetime value is even more truncated.

This customer values your rate and not your service or relationship. This is ironic, as you likely marketed this product by telling your prospects how you are offering 8x the national average on rate because you value the relationship.

If you try to market the next best product to this customer (which is a retirement account for the owners and then an HSA account for the business), you will find that you will spend more money than average in acquisition costs and/or have to offer the lowest loan rate and the highest deposit rates to open that next account.

The lower expected life and rate sensitivity likely results in a greater customer churn rate. The high-yield bank must keep acquiring new customers to offset the churn. New acquisition, sales, marketing, support and management costs drive up the operating cost overtime further hurting profit.

Monte Carlo Simulation Comparison

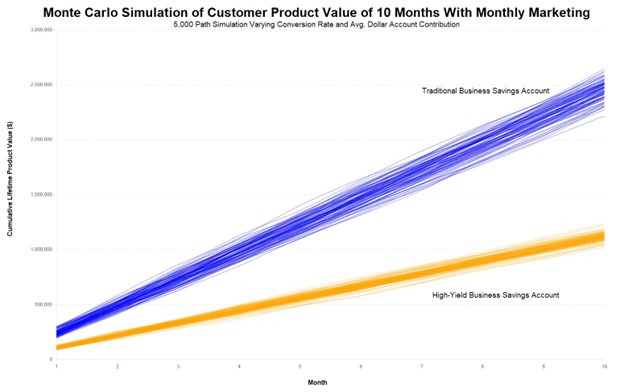

The advantage of the high-yield account is that it can quickly and efficiently (other than the interest expense) gather deposit balances. We set up a Monte Carlo model to simulate marketing both the traditional and high-yield business savings account. We used actual conversion data and had the model create 5,000 different “paths” of various conversion rates and account deposits. The marketing was based on either new account opening or reminders to existing customers to contribute to the respective accounts.

At the end of ten months, the high-yield account had an impressive $40 million in balances opening 6,400 new accounts. This blew the traditional savings account away that only had $8.7 million in balances and 1,550 new accounts. In short, marketing a high-yield account was almost five times more effective in meeting a balance objective.

However, if your goal is to build value, then marketing the traditional business savings account was superior. While balance building is 5x slower, value building is 15x greater. As such, profit and cumulative lifetime value is greater at every sale. This compounds and despite greater variability in sales, the product accretes significantly more value that compounds to make a more profitable bank in both up and down rate cycles. The higher rates go, the more effective a traditional business savings account is.

And Then There is the Employee

The worst part of the high-yield deposit strategy is what it does to your employees. Employees quickly learn that it is OK to pay a high rate to attract a customer. They then learn that you have to keep paying a high rate to keep the customer. This training gets ingrained, and after several years, your bank loses the art of growing and managing deposits.

When banks stop paying a high rate, they often take it out on the employee thereby hurting morale. Moreover, lower profitability also means lower compensation to the employee. The combination of all these factors means employee churn increases, driving up operating costs.

Doing Better Than a High-Yield Account

Leading with credit is a traditional tactic that is sometimes overlooked. It is far better to give up 25 basis points on a reduced rate for a loan and get both a transaction and business savings account in the process than paying an extra 3% in deposit balances. Even if economically more expensive to start (depending on the size of the loan and deposit balances), it gets you a better-performing customer over time. Lock in a long-term loan and requiring deposit balances is one easy tactic to reduce acquisition costs and improve deposit performance.

Another key to separating your bank from the competition is using anything BUT rate to market and build product features around it. Instituting savings alerts, and gamification, allowing for subaccounts, prize-linked savings, savings round-ups, smart automated transfers, sweep accounts, and other innovative features can drive acquisition cost down and engagement up. For that matter, we are still shocked at the fact that a large number of banks still do not have the ability to allow prospects to open business savings digitally.

Banks that want to drive deposits should start with paying compensation to increase the opening of business savings. This is another often overlooked tactic and can serve banks well to drive deposit balances.

Targeting specific industries such as high-tech manufacturing, insurance, payment companies, law firms, hospitality, and many others has more of a need for business savings, which results in a shorter sales cycle and lower acquisition costs. Better still, these firms tend to have average balances above $60,000, thereby helping the economics of the product.

Putting This Into Action

While using rate as an offensive weapon is always tempting, it is lazy banking. Strategically, paying rate often prevents the development of the products, culture, marketing, and relationship management that is needed to build long-term franchise value through any rate cycle.

High-yield accounts result in a quick hit of balances but sap a bank of needed capital and profitability to invest in the long run. It is better to slow growth and build profitable products and customers for the long run than sacrifice the quality of the balance sheet and income statement.

While you can rationalize paying a rate in place of marketing and acquisition costs, paying a high rate for deposits gets you more rate-sensitive customers that cost you more in the long run. Credit card companies and specialty banks such as Capital One, Bank, and Ally can afford it because of their margins, but most banks cannot.