Fair Value Accounting for Loans

Fair value accounting measures assets and liabilities at current market value instead of historical or amortized value. Most agree that attempt to fair value certain financial instruments would still not approximate the settlement of that instrument between a motivated buyer and seller – for example, there are many unpredictable or unknown factors to be able to value instruments like loans and deposits. Nonetheless, with the recent collapse of sizeable regional banks, regulators, investors, analysts, accountants, and bankers are now scrutinizing the fair value of banks’ securities and loan portfolios. This development should strongly motivate community banks to consider the benefits of loan-level hedging.

Fair Value of Loans

The fair value of securities has made recent headlines with a focus on regulators, legislators, and bankers. Silicon Valley Bank’s failure was spawned by the decrease in the fair value of securities caused by an increase in interest rates. But many banks have more significant fluctuations in fair value in their loan portfolios (because of the same rise in interest rates.)

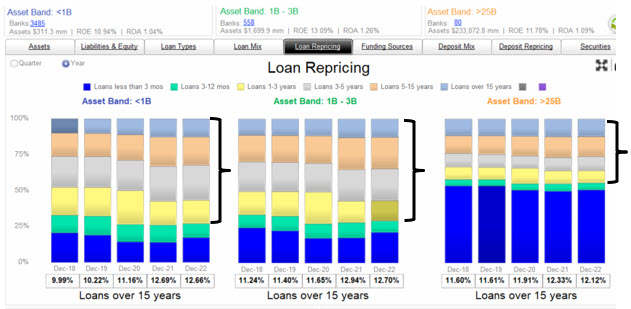

Most banks’ fair value sensitivity is greater in the loan portfolio because, for the average bank, loans comprise a larger percentage of the balance sheet. Further, many consumer and commercial borrowers have recently demanded fixed-rate loans to protect their cash flow. The graph below shows loan repricing buckets for three asset-sized groups of banks: under $1B, $1B to $3B, and over $25B in assets. Smaller banks have a higher percentage of fixed-rate loans than larger ones, as the black-colored brackets note. The proportion of fixed-rate loans has increased for community banks over the past four years. In contrast, larger banks have more loans in the variable bucket, and their fixed-rate loan portfolio has held relatively steady in the past four years.

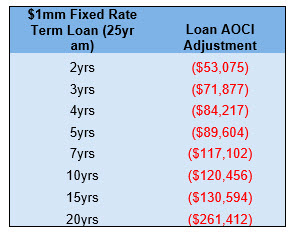

Each basis point increase in rates decreases the lifetime value of a fixed-rate loan to a bank. This is similar to the effect higher rates have on “accumulated other comprehensive income” (AOCI) for fixed-rate securities. The longer the fixed rate, the more sensitive the loan is to negative economic adjustment. The table below shows fair value adjustment on various term fixed-rate loans based on interest rate movement over the last year. The table below shows the negative AOCI of various fixed-rate loans with different contractual terms given interest rate movements over the past year.

A $1mm in principal, 25-year amortizing loan, with now a five-year maturity, in the last year, recognized a negative AOCI of approximately $90k, and the economic value of that loan is $910k (a 9% reduction in economic value). A $1mm in principal 20-year maturity loan in the last year had a negative AOCI of $261k (a 26% reduction in economic value).

Empirical Evidence

We reviewed the fair value footnotes at year-end for First Republic Bank, Western Alliance Bank, and Citizens Business Bank because those banks’ fair value adjustments have been in the news recently. First Republic’s fair value adjustment (decrease) for all loans at year-end was $22B, greater than the bank’s total Tier 1 capital of $17.5B. Western Alliance’s market adjustment (decrease) for all loans at year-end was $3.9B, compared to $5.5B in Tier 1 capital. Citizens Business demonstrated an adjustment (decrease) for all loans at year-end of $920mm, compared to $1.52B in Tier 1 capital.

The Wall Street Journal recently reported that 100 public banks had fair value adjustments on loans and securities that equaled 50% or more of those banks’ equity. While community banks have a smaller percentage of uninsured deposits (compared to First Republic, an example, at 68%), community banks face another issue. Depositors view the largest national banks as safer because they are perceived as too big to fail and implicitly backed by the government.

Recommendations

Some bankers and analysts dismiss fair value adjustment as not reflecting economic value. They may argue that as rates fluctuate, valuation is just as likely to go up as go down. We have seen that in a rising interest rate environment, fixed-rate loans extend duration and fair value is adjusted down, but in a declining interest rate environment, borrowers prepay their obligations eliminating the positive fair value adjustment for the bank. This is the classic case of negative convexity created with free options for borrowers. Other bankers argue that the horse is out of the barn, all the negative value has been realized, and interest rates are poised to decline. We believe that prudent risk management is not predicated on trying to predict interest rates relative to the forward curve. Interest rates will fluctuate many times throughout the average life of a loan, and bankers should eliminate interest rate risk that can hurt the fair value adjustment on their loan portfolio.

Community banks should seek a loan hedging program that will work for their business based on their market, products, competition, and sophistication of the lending team. A loan hedging tool can generate additional fee income, increase net interest income (NIM) with the current inverted yield curve, and help keep regulators and analysts satisfied that the loan portfolio is not subject to fair value risk with changing interest rates.