Getting Paid for Fixed Rate Loan Risk

Bankers agree that reward (revenue) is a prerequisite for accepting risk. It would make no sense to risk the bank’s capital without adequate compensation. However, to avoid commercial fixed rate loan risk, the first crucial step is to measure that risk. We will show how banks that start to accurately measure interest rate risk embedded in a loan immediately seek compensation for that risk.

Fixed Rate Loan Example

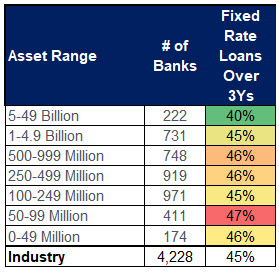

Almost half a bank’s loan portfolio is fixed at three years or more (below). We work with hundreds of community banks across the country who use loan hedging programs to eliminate interest rate risk and reduce credit risk. These hedged loans are priced at a predetermined credit spread over 1-month term SOFR, where the fixed rate to the borrower is determined at the time of the loan closing by adding that credit spread to the base rate (or hedge rate). The borrower is provided with indicative rates leading to closing, and a forward rate lock is available, but most borrowers lock the fixed rate at the closing table based on the prevailing hedge rate. That hedge rate may be lower or higher than the indicative rates provided depending on market conditions and treasury/hedge rates at the time of closing. We call this type of hedged loan transaction “fixed at closing.”

There is another form of hedged loan, called “fixed in advance.” Some borrowers ask the bank to fix the rate a few days in advance of closing (without using a forward rate lock agreement). This type of fixing arrangement would subject the bank to a few days of interest rate risk, where the fixed loan rate to the borrower is established in advance, and the bank’s credit spread is solved by subtracting the prevailing base rate from the fixed loan rate. We have closed thousands of hedged loans, and we can count on one hand the number of times that community banks have agreed to use this “fixed in advance” closing. Why? Community banks do not want their credit spread to be subject to interest rate movements (even for a few days of exposure), and if the bank seeks a specific margin, it wants to be certain that it will obtain that margin.

But ironically, that same community bank will not hesitate to make an on-balance sheet fixed rate loan (without a hedge), for the entire term of that loan – some community banks will take up to five years of interest rate risk exposure without concern that their margin will be unknown and will vary widely as interest rates and cost of funds moves over the loan term. We think that the explanation for this irrational behavior is simple – the on-balance sheet loan interest rate risk is not measured and becomes part of the noise of asset liability management. In other words, if you do not, or cannot, measure the risk, you are less likely to manage it. The “fixed in advance” hedged loan clearly demonstrates the impact of interest rate movement on the value of the loan, but the fixed rate on balance sheet loan hides this interest rate risk.

How Community Banks Can Manage This Risk

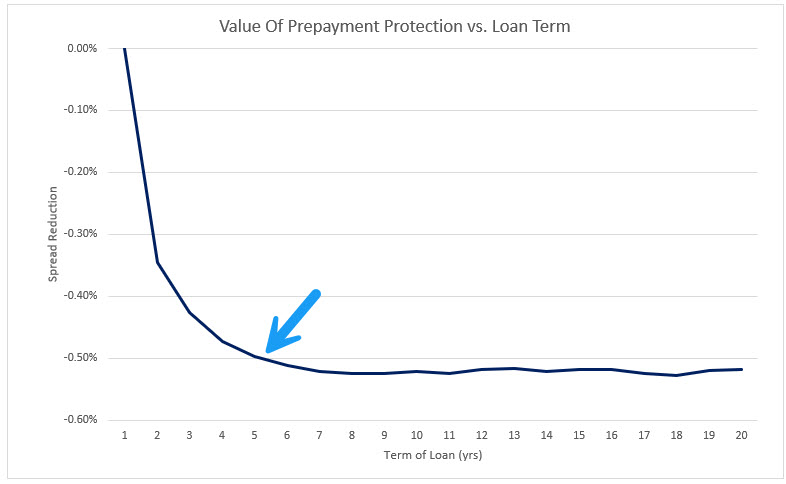

There are two steps to mitigate this on-balance sheet interest rate risk in commercial loans. First, a credit risk premium must be charged for these loans to compensate the bank for the possibility that interest rates will rise in the future, causing NIM contraction. We have written about this concept before and most notably here. In summary, and depending on volatility, type of borrower, and term of the loan, the on-balance sheet commercial term loan must be priced between 50 and 60bps higher than the same hedged loan. Second, is that these loans must include a strong prepayment provision so that if rates fall, that the bank does not lose the earning asset without compensation, and we have also written about this in various articles and most recently here. In summary, and depending on volatility and term, the prepayment provision must be firm and start at an equal percentage of the contractual number of years of the loan, declining one percent each year.

Below is a graph showing the value of the optionality for a loan that doesn’t have any prepayment protection. For example, a five year loan without a prepay provision costs the bank approximately 0.50% per year. For a $3mm loan, that is a potential loss of $75,000 over the life of the loan just from optionality. This is in addition to the fixed rate risk that could be embedded in this loan.

The counter argument has been that interest rates are as likely to fall as to rise, and overall, the bank is neutral because over a five-year span interest rates will rise and fall, and the bank’s NIM will be neutral. Put another way, the argument is that over the long term, the bank should be indifferent to interest rate movements for fixed rate loan exposure. But this argument is flawed. First, when interest rates rise, fixed rate loans extend duration, thereby hurting the bank. Second, when interest rates fall loans prepay and many banks either do not have appropriate prepayment provisions or do not enforce such provisions (especially when the borrower refinances with the same lender), thereby again hurting the bank. This is a free option that banks are giving away to their borrowers that creates one-way floaters – loan yields only go down.

Conclusion

Over the last 40 years, community banks reluctantly retained fixed-rate loan maturities and without the benefit of measuring that risk, the reward appeared sufficient. However, in an era of a flatter yield curve and greater volatility, this strategy can be painful for many banks.