One-Way Floaters and Why Banks Should Avoid Them

If not properly structured, fixed-rate commercial loans can become one-way floaters. The term refers to a loan where the bank retains the fixed rate when interest rates rise, but the borrower refinances the loan when interest rates fall resulting in declining yield for the bank. In this article we explain why this reduces profitability for the bank and how bankers can avoid this trap.

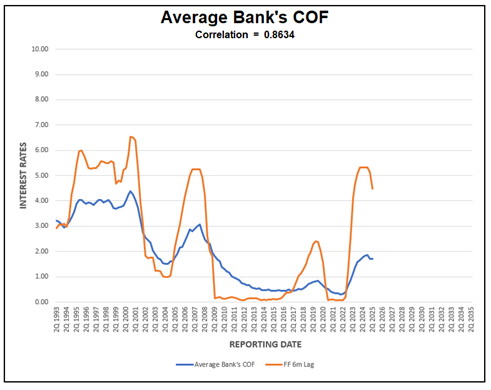

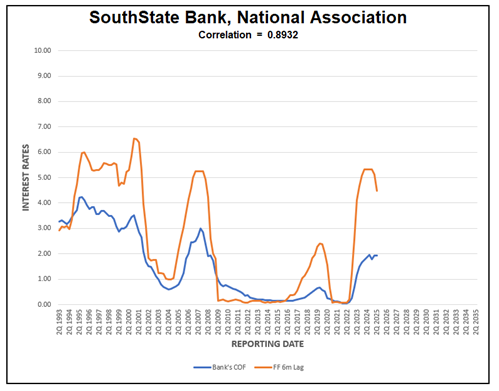

Banks’ COF and Short-term Rates

Most banks’ cost of funding is highly correlated to shorter-term rates, and banks generally prefer shorter loan duration – that is floating, adjustable, or fixed rates of up to one to two years. The entire banking industry COF correlation to Fed Funds and SouthState Bank’s specific COF correlation to Fed Funds is captured in the two graphs below. We can run your bank’s COF graph if you would like to see it – email us at ARC@southstatebank.com.

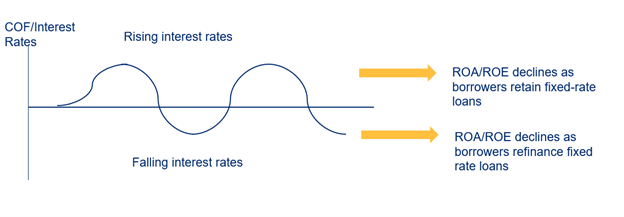

When banks offer commercial fixed-rate loans, borrowers are motivated to extend duration for as long as possible during periods of rising interest rates and refinance the loan when interest rates fall. The graph below shows how the cyclicality of interest rates coupled with fixed-rate loans diminishes banks’ performance.

We believe that this phenomenon is primarily the result of lack of measurement. Banks will book loans that make a certain NIM hurdle at inception without continuing to measure ongoing possible NIM contraction or expansion.

The other major reason for one-way floaters is lack of appropriate loan prepayment provisions. Unfortunately, many borrowers often negotiate away the prepayment provision since many banks do not quantify the economic value of a prepayment provision. Many banks will waive the standard declining balance prepayment provision if the borrower refinances within the bank. Banks will also reprice the loan to current market rates if pushed by borrowers. Regardless of the reason for prepayment, over time, and through multiple rate cycles, this behavior results in substantial decrease to a bank’s ROE.

For sophisticated borrowers, prepayment provisions are tricky to apply. Sophisticated borrowers have multiple credit facilities, access to liquidity, and may generate substantial free cash flow. Those sophisticated and liquid borrowers (the credit quality that many banks seek), can pay off above market fixed rate loans with cash on hand, and place new, lower-priced debt, at a future date. Thereby, negating the prepayment provision in its entirety.

How To Avoid One-Way floaters

While banks may want to keep loan duration short, borrowers often prefer longer-duration loans to help stabilize cash flow, minimize refinance risk, and reduce loan origination costs. Therefore, given a choice, many sophisticated borrowers are looking for longer loan duration to decrease their risk, with about the same interest costs. Banks must offer customized solutions that meet their clients’ needs or risk losing profitable business.

There are three steps that community banks must take to counter this one-way floater and the resulting dilution of return for the bank:

- Banks are well served to include and enforce a strong prepayment provision where it makes sense to do so. If interest rates fall the bank will minimize the loss of an earning asset. Prepayment provisions not only protect banks against one-way floaters, but they also increase stickiness and cross-sell and upsell opportunities for banks.

- But prepayment provisions do not help banks with fixed rate loans when interest rates rise (margin continues to contract). To counter this erosion in ROA/ROE banks must charge a premium for fixed rate loans. This risk premium will depend on volatility in the market, inflation risk, type of borrower and loan category, but in summary this premium has historically been 50 to 60bps over the equivalent floating rate. We have written about this concept before and most notably here.

- Since it is impossible to consistently outwit the market – equity, debt, or any other highly active market, neither the borrower or the lender can be certain that we are entering a declining or increasing interest rate environment – especially over multiple years. Many community banks eliminate the one-way floater by offering their borrowers the ability to fix the loan rate from 3 to 20 years through a hedge. The hedge not only solves this issue but results in a stickier relationship and can generate substantial hedge fee income. Most regional and national banks view this as the preferred solution rather than charging a risk premium on the loan (for highly desired client) or trying to enforce a prepayment provision with its attendant reputation risk.

Conclusion

Over the last 40 years, many community banks reluctantly retained fixed-rate loan maturities of up to 5 (or sometimes longer) and the behavior resulted in one-way floaters. Currently this strategy is not preferred by banks given the flat yield curve and volatility in the economy. While every community bank’s balance sheet composition is different, the market and current interest rate projections create a poor environment for adding more one-way floaters.