How to Practice Loan Pricing Discipline

Community bankers need to practice realistic loan pricing discipline. However, we need to understand the meaning of pricing discipline and its effect on community bank performance. In this article, we would like to define loan pricing discipline and cover bid, why it matters, and demonstrate how most community banks currently are not using loan pricing discipline.

Loan Pricing Discipline and Cover Bid

Some bankers believe that loan pricing discipline entails setting minimum credit spreads for all loans and ensuring all credit facilities meet a minimum yield. Unfortunately, this is both incorrect and often leads to bank underperformance. Treating all credit facilities equally by setting minimum credit spreads regardless of size, term, cross-sell opportunities, lifetime value, and credit quality leads to misallocation of capital and substandard return on assets (ROA) and return on equity (ROE).

Credit pricing discipline means setting loan pricing parameters to reach a minimum ROA/ROE using realistic assumptions about the risk/return for a specific client relationship. Bankers need to manage credit relationships to ROA/ROE and not credit spreads. Further, bankers need to be realistic about assumptions such as usage, probability of default and loss given default, and cross-sell opportunities (such as deposit size, deposit stickiness, and deposit costs) – all of these inputs are forward-looking and must be modeled, stress-tested, and adjusted with market changes.

Many banks target profitable commercial clients. The reality of booking new loan business is that the winning bank has offered the lowest price or most accommodating credit structure. When a bank wins a loan, it is imperative that the banker understands the cover bid. The cover bid in a competitive situation is the second-best bid to the client. Bankers need to understand how they won the loan and what the competition was offering. If a lender wins a loan with a credit spread of 2.00% and the next best loan spread offered to the borrower was 3.00%, that lender gave the borrower a 100bps advantage to the cover bid – not an optimal pricing choice for the winning banker.

Market Intelligence

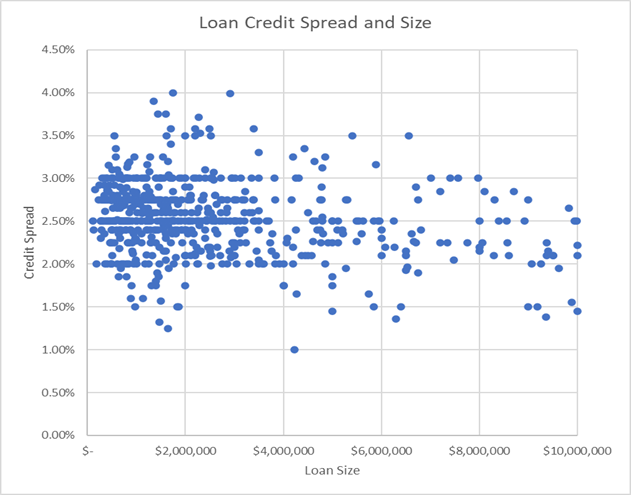

We analyzed the last 1000 loans priced on our hedging desk, and the credit spread, and size are plotted below. While the average credit spread is 2.51% and the average loan size is $3.3mm, roughly 75% of all these loans are priced to a minimum credit spread and not for a target ROA/ROE. This can be seen with most loans priced to an arbitrary credit spread (2.00%, 2.25%, 2.40%, 2.50%, 2.75% or 3.00% credit spread accounts for about 75% of the loans). If this universe of loans were priced to an ROA/ROE target, we would expect a wider dispersion of dots across the credit spread axis.

Further, when we adjust the loans for credit quality and only include A-quality loans (loans with 1.50X debt service coverage ratio (DSCR) and below average loan-to-value (LTV)), the same conclusion can be reached – banks are not using pricing discipline in the true sense of the definition. We find a near-zero correlation between credit spread and a) loan size, b) DSCR, or c) LTV. This is strong evidence that community banks are pricing to an arbitrary minimum credit spread in this set of loans.

Objectives of Loan Pricing

We believe that all national banks and most banks over $10Bn in assets (regionals) are using some version of a risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) loan pricing model. Only about 20% of community banks (banks under $10Bn in assets) are using such a model. The national and regional banks originate about 85% of all domestic loans, and community banks hold the remainder. Why do banks use RAROC loan pricing models? The most common reasons are as follows:

- Increase granularity of credit pricing

- Accurately allocate capital

- Maintain lender discipline to minimize cover bid

- Educate management and lenders

- Become more attuned to prevailing market conditions

- Standardize pricing across divisions, product lines, and relationships

- Increase profitability

- Decrease risk

- Manage customer relationships

- Enhance reporting, control, and governance

Why Minimum Credit Spreads Do Not Lead to Higher ROA/ROE

While it may appear that the easiest way for bankers to increase performance is to increase loan yield, the results are unfavorable.

Requiring minimum credit spreads for commercial loans has the following consequences:

- Despite management’s best efforts, lenders interpret the minimum spread as the only spread available to their customers. The starting point that is meant to be a floor (the minimum credit spread) inadvertently becomes the pricing ceiling or cap. In the long term, this strategy may decrease the average credit spread for the bank instead of enhancing it.

- There are three ways that managers can price their loans (or any product or service, for that matter):

- Price to the competition. Banks determine where competitors charge for similar loans in the marketplace and price accordingly.

- Cost-plus pricing. Here, banks calculate their cost of capital, funding costs, and all direct and indirect costs and add a margin to determine the price.

- Perceived value to the customer. While more subjective, the bank determines the maximum a borrower will pay for the perceived value of the banker’s expertise and the problem the bank is solving. This is the optimal way for banks to price their loans to increase ROE.

But when banks institute a minimum credit spread, that minimum spread is typically based on what the competition is pricing (or above if the bank wants to minimize loan growth). Managers look at the average spreads in the market and set their minimum spread relative to that industry average. However, pricing to the competition is the worst pricing choice for banks. Pricing to the competition is an abdication of management’s duties because it effectively transfers an important corporate power to the competition. While bankers should be aware of the prevailing pricing in their market, that information is used correctly to make a buy-or-sell decision (make a loan or buy a security), not to match or follow the competition. The above is true in most industries, but in banking, pricing to the competition is even more derelict because the decision is not just about revenue but also the extension of credit. The better way for banks to price loans is based on perceived value to the customer, and minimum credit spreads force bankers away from that pricing principle.

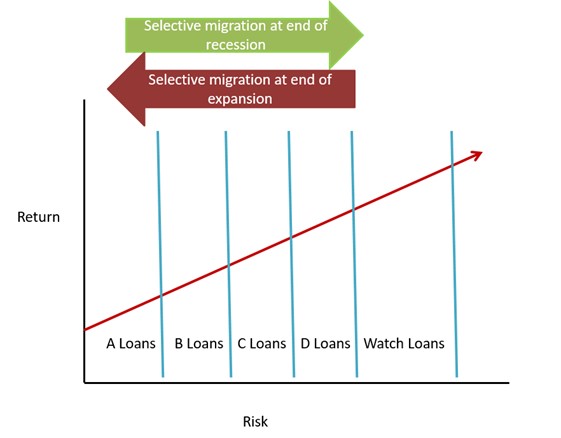

- To optimize loan portfolio profitability, community banks must recognize how to migrate through the credit spectrum (see an example of the concept in the graph below). During long periods of expansion, banks misprice credit risk more severely. In a recession, better credit-quality loans have a higher risk-adjusted ROE. Banks want to capture better credit-quality loans when the economy is expected to slow and liquidity to decrease. Banks can avoid negative selection bias by selecting the correct credit quality in anticipation of the change in the economy. For example, suppose a bank is not anticipating changing economic conditions and generates credit quality across the spectrum in a downturn. In that case, the competition will scramble to steal high credit-quality loans and avoid the lower credit-quality loans, naturally decreasing the average credit quality of the portfolio for that bank. A minimum credit spread strategy is inherently set up to capture lower credit-quality credits because management typically sets the minimum spread to capture more yield, not to funnel high-credit quality at a lower yield.

- The minimum credit spread strategy magnifies survivorship bias in banking. Survivorship bias is the logical error of concentrating on outcomes that made it past some selection process and overlooking outcomes that do not make the selection process. The issue for many banks is this: the performance of all loans should be measured over the life of those credits, but most banks only measure performance quarterly on financial statements looking backward. However, the profitability of an individual loan going into the portfolio is not measured at inception because minimum credit spreads are not a measure of profitability, and minimum credit spread has no actual causal relationship to profitability.

Survivorship bias occurs at banks using minimum credit spread because the more profitable loans (the ones with the lower credit spread and better credit quality) are heavily underrepresented in that bank’s portfolio. Managers are then challenged to increase the bank’s ROE and choose loans with an even higher yield but, unfortunately, lower collective ROE. The profitable/lower-risk loans are not even vetted by management because lenders follow minimum credit spread guidelines.

Conclusion

Banks cannot practice realistic loan pricing discipline without being able to measure ROA/ROE for each loan predictively. Pricing discipline requires the ability to assess and forecast credit quality, credit usage, relationship cross-selling, and lifetime value of the customer. In our future articles, we will discuss some of those relationship parameters and how they affect bank performance.