Loan Risk and Return – The Two Loan Riddle

It is rare that banking lends itself to a logic test, but we have been trying this loan risk and return riddle on hundreds of bankers across the country for years, and only a few bankers choose the correct answer. The riddle goes like this: You are presented with two loans. Loan A is priced at SOFR plus 1.50%, and Loan B is priced at SOFR plus 3.50%. The loans are originated concurrently by different banks to different borrowers. The loans are the same size, same maturity dates, originated in the same geography and have similar anticipated cross-sell opportunities. Assume both banks and both borrowers are rational financial entities. Which loan would you take – A or B?

Most bankers think about this problem for a moment, conclude the difference between the two loans must be credit, and choose Loan B since it is priced with an extra 2.00% margin. Since they do not know the credit quality of either loan, they prefer the one with the extra yield. We believe the correct choice (leading to a higher return on assets (ROA)/ return on equity (ROE)) is Loan A. The reasoning also explains why banks should not use credit underwriting as a competitive differentiator – or put another way, community banks are not in the business of competing for credit risk.

Loan Risk and Return Analysis

The distracting feature for most bankers is that they are taught early in their career that they are in the business of taking risk and without taking risk banks would not earn profits. We believe any businesses in most industries take some form of credit risk, but banking is a different animal. Empirical evidence and common sense lead us to believe that the willingness in banking to take higher yield for higher credit risk is a losing tradeoff.

Most bankers are familiar with the concept of loan risk and return tradeoff, which states that potential return rises with an increase in risk. Low-risk assets pay lower returns, whereas high-risk assets pay higher returns. Assume now that loans are priced efficiently (which they are not), and your bank is in the business of taking credit risk for yield, then each loan will translate to the same ROA (portfolio effects excluded). believe credit is efficiently priced, then the risk-return relationship is shown in the graph below. Each loan is priced on the red line, and in the long run, all banks would earn the same ROA (excluding specific operational differences).

Let us relax our assumption that loans are efficiently priced. In reality, the market (i.e., lenders and borrowers) is not clearing loan prices efficiently, and many loans are priced above or below the red line. Smart bankers want to get loans above the red line and avoid loans below the red line (more yield for the same risk, or less risk for the same yield). Here, the analysis gets more interesting; bankers do not seem to make mistakes evenly above and below the line. Risk-return tradeoff mispricing occurs much more frequently on more risky credits than on less risky credits (mispricing is more common on the right side of the graph).

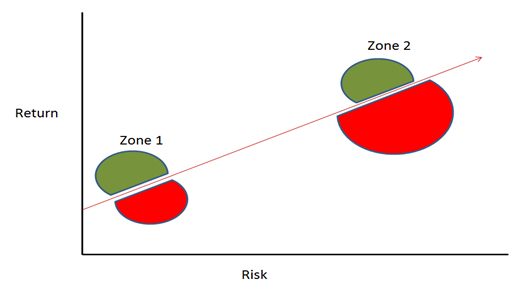

The graph below identifies two zones: Zone 1 is the possible mispricing around a low-risk asset (assume a credit riskless loan), and Zone 2 is the possible mispricing around a loan with a high probability of default and high loss-given default.

Bankers tend to underprice higher-risk loans (those in Zone 2) to a greater extent than lower-risk loans (those in Zone 1) for the following reasons:

- Riskier credits have a wider dispersion in performance (the dispersion around the expected probability of repaying is wider), leading to more possibility for mistakes.

- Credit risk is a distant cost, while yield is an immediate gain. Humans tend to favor immediate gratification at the expense of a distant cost. During periods of economic growth, bankers are notorious for mispricing credit.

- Bankers are typically paid incentives for higher yield, but the bank’s shareholders must pay for future credit mistakes. This is a classical agency/principal dilemma.

- Competition is constantly leading us astray in pricing. The adage in the industry has been that you can only perform as well as your dumbest competitor. If your competition is underpricing credit risk, the borrower is more than willing to take that capital, and your only choice is to lose the loan. It is more likely that some lenders will inevitably make a risk analysis mistake on the riskier loan than the less risky loan (which comes with a lower yield).

- Risk is priced more rationally during a recession; however, recessions are comparatively rare and short events compared to economic expansions. Therefore, most of the time banks are competing during periods when euphoria abounds, and discipline is lacking.

Because of the above factors, the risk-return tradeoff is not a straight line but a set of semicircles like the graph above. Between Zone 1 and Zone 2, banks want to land in the green semicircle and avoid the red semicircle. Unfortunately, the red semicircle in Zone 2 is quite large, and many banks get trapped in the game of wanting to outwit the market (gain additional yield without taking the additional risk to demonstrate higher ROA).

Empirical evidence also shows that between different banks there is no relationship between yield and ROA. Banks that want additional yield may be willing to take additional risk, but by taking the extra risk, banks take on more future credit loss and, thus, a lower ROA in the long run. The reality is bankers are unable to correctly measure credit risk through a business cycle.

Conclusion

Pricing conveys information. The correct answer to our riddle is Loan A – it is priced at a lower credit spread because it is a lower credit risk, and mistakes in credit pricing are less severe for better credit quality loans. Loan A is also likely to contain positive selection. Loan B is likely only taken by borrowers who have fewer banks competing for their business, have greater credit risk and is therefore less liquid. This lower liquidity can add 25 to 150 bps of additional risk per annum depending on risk profile, structure and collateral.

We believe a bank’s long-term ROA would be optimized by deemphasizing underwriting higher-risk credits and concentrating on operational efficiencies to make the business model profitable with lower-yielding assets. It appears that for the average bank, and in the long run, the risk-return tradeoff for credit risk erodes shareholder value. High performance in community banking comes from forming long-term and sticky relationships instead of pay-for-risk capital allocation.