Why Commercial Loan Prepayment Speeds Matter

The biggest surprise for bank managers using risk-adjusted return on capital (RAROC) loan pricing models is the low return on equity (ROE) on smaller, shorter, and lower-credit quality commercial loans. Those ROEs tend to subtract substantial value from the bank and show negative returns – sometimes in the negative double digits. However, one aspect that many bankers do not address when using RAROC models is that prepayment speeds are a significant driver of negative ROEs, and adjusting loans for expected life, rather than contractual life, is a big source of loan portfolio underperformance.

Loan Prepayment Speeds Explained

Residential mortgages are more homogenous, and many firms have developed highly predictive models to calculate prepayment speeds based on past behavior, portfolio makeup, and macroeconomic variables. However, little public research is available on prepayment speeds of commercial mortgages – this is understandable because of the uniqueness of each commercial loan. Even sophisticated loan RAROC models do not incorporate the value of prepayment speeds in calculating the ROE or net present value (NPV) of income.

The issue for community banks is that smaller commercial loans (loosely defined as under $1mm) almost always originate at a premium cost to the bank – meaning that the value of the loan is below par at inception. Why is that so? The answer is that the cost to originate a commercial loan is almost always higher than the upfront fee paid by the borrower. Most banks’ origination costs (marketing, underwriting, documentation, and funding) are higher than the fee charged on origination. Therefore, if the loan origination cost is 2% of the principal, and the loan fee is 1% of the principal, the value of the loan at inception is 99%, and if the loan prepays on the day of origination, the bank has lost 1% of the value of the principal. As the loan seasons and interest payments are made, the bank starts to earn a positive return on the loan. The problem is that most bankers do not measure instrument level ROE for loans and just look at combined portfolio RAROC; worse, they only view the quarter-end GAAP return on equity (a snapshot of one period return for all products and relationships at the bank).

Some bankers may (and have argued) that their overhead costs are fixed, so if the bank does not originate a loan, the assumed 2% origination cost is still incurred because those employees, branch network, and corporate costs must still be paid. This is an incorrect argument because all costs are variable in the long run, and the strategic analysis by management must be based on the long-term business model of the bank and not on the incremental overhead cost of a loan. If the argument is, “Why not make these below-hurdle ROE loans, since I have the overhead costs regardless,” then the long-term outcome for the bank’s business model is not viable.

The Culprits

The commercial loans most affected by prepayment speeds are construction through perm where the perm is not locked at closing, stabilization loans, improvement loans, substandard credit loans (because if the loan quality improves, the loan prepays, and if the quality deteriorates, the loan ROE plummets further), and lines of credit used to finance longer-term assets vs. working capital fluctuations. In summary, any loan with low switching costs and providing the borrower a free option to refinance is a culprit.

We used our model to analyze the NPV of income for commercial loans based on assumed prepayment speeds and loan size. The result of our research is not surprising, and we have seen these results over numerous credit and interest rate cycles. Bank value can be eroded by not measuring and managing prepayment speeds on commercial loans. We believe that all community bank lenders need to understand this critical value driver.

Our Model

In our model, we vary prepayment speeds based on conditional prepayment rate (CPR). CPR is the portion of a loan or pool of loans that pays principal ahead of the loan’s preset amortization schedule. These calculations are vital and have been modeled for mortgage-backed securities for decades.

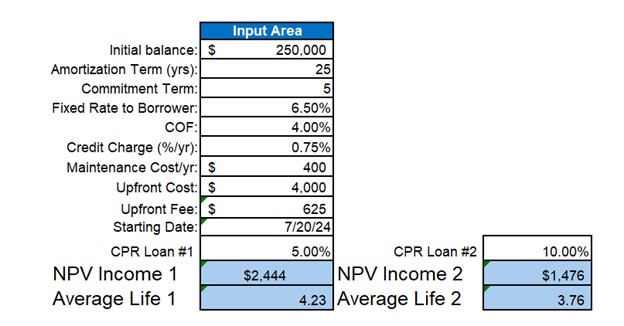

Our model allows us to input parameters of a commercial loan such as loan amount, amortization, interest rate, cost of funds (COF), upfront fees, annual maintenance costs, credit charge, and loan origination costs. We can then make different assumptions on prepayment speeds as measured by CPR and value two outputs: NPV of income and the average life of the loan (or portfolio). An example of the inputs and outputs appears below.

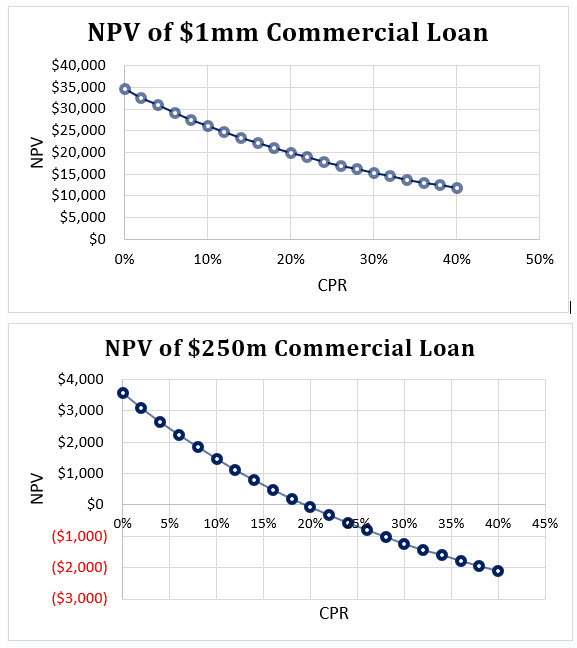

We ran this model on different loan amounts and different assumed CPRs. We performed a sensitivity analysis to understand how CPR affects loan profitability as measured by net present value of income. The output of the relationship for a $250m and $1mm commercial loan appears in the two charts below (for a 25-year amortization, five-year term).

Simply put, higher prepayment speeds decrease loan profitability. Seeing the math underlying the concept of expected loan life, or prepayment speed as measured by CPR, is enlightening. The charts above show that the NPV of income falls dramatically as CPR increases. That specific effect is more pronounced on smaller loans. A profitable $1mm commercial loan at 0% CPR becomes barely profitable at 40% CPR. A profitable $250m commercial loan at 0% CPR becomes unprofitable at only 20% CPR, and we estimate that average community bank CPR is 20% to 30% (with some loans closer to zero and some above 50%).

Higher CPR is a major cause of decreased profitability for many lenders. The reason that NPV of income (and ROE) are so sensitive to prepayment speeds is that commercial loans have thin profit margins after accounting for ongoing costs such as COF, credit charges, and loan maintenance costs. Most importantly, commercial loans have high upfront origination costs. Without the time necessary to earn that thin margin, a bank cannot recoup its cost of originating the credit. It is only with long and stable periods of earned margin that the commercial loan becomes profitable. This behavior is especially pertinent for smaller credits – and the average commercial loan size at community banks is between $250k and $500k at inception.

Key Lessons on Loan Prepayment Speeds

We believe that there are two important lessons from our research. First, bankers need to understand how their loans prepay and take this into account for pricing decisions. At the same institution, there are categories of loans that will have low CPRs (below 5%), and other commercial loan categories may have CPRs above 20%, 30%, and in some cases, even above 50%. Bankers need to understand how their loans behave to make proper pricing and relationship decisions. What may look like a desirable credit may not be so profitable after considering the anticipated prepayment speed (and vice versa).

Second, bankers must strive to decrease CPR on commercial loans to increase profitability. Most loans can be made more profitable with a longer stream of income. Again, most loan pricing models do not track, predict, or measure prepayment speeds and community bankers are left to their intuition to try to maximize profits.

Conclusion

The next time you compete for a commercial loan, and find that the margin, the fee income, or cross-sell opportunities are not attractive, consider the expected CPR for that loan. What may appear to be an irrationally priced loan, may be the correct market clearing price for a long-term, stable, earning asset with a strong prepayment provision that translates to a lower CPR and higher profitability.