Could the Next Rate Move Be Up in 2026?

The dominant market story for 2026 is inflation is cooling, and employment market is uncertain, so the Federal Reserve will keep trimming rates until policy looks comfortably “neutral.” But the current evidence points to a less comfortable possibility: the Fed may be done cutting for a while, and if inflation risk re-accelerates or employment levels remain stable – the next rate move in 2026 could be no move at all, or even a hike.

This next rate move outcome is not a contrarian view for contrarian-sake, but a synthesis of three hard-to-ignore signals: First, the 2024–2025 easing cycle has not actually eased the economy the way rate cuts normally do. Second, the Fed itself is more divided than it has been in years, with a meaningful group already leaning “no more cuts.” Third, structural forces—fiscal deficits, term premia, and investment booms (notably AI/data centers) are pushing up the economy and its inflation risk at the same time. Put those together, and you get a 2026 setup where the Fed cannot safely “pre-commit” to easing and may have to defend credibility with a steady hand, or higher rates, especially if inflation surprises to the upside.

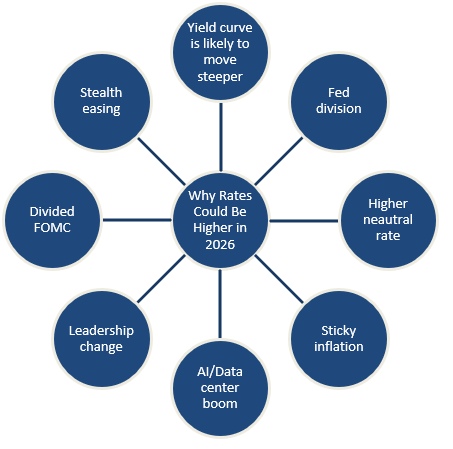

9 Forces to Observe To Determine the Next Rate Move

There are nine sound reasons why the Fed’s next rate move may not be a cut.

- Since September 2024, the Fed cut short-term rates by 175 bps, and long rates still rose. If the Fed cuts rates aggressively, the intended consequences would be that borrowing costs across the economy would fall and financial conditions would ease. That’s not what happened, and instead, long-term rates (5 and 10-year treasuries) are higher than when the Fed began cutting. If growth accelerates from here, rising term premia could push yields higher and might mean any further easing by the Fed would lead to higher term rates, and tighter financial conditions – not the right move in the tradeoff between inflation and full employment. The bond market is effectively telling the Fed that cuts are not translating into sustainably lower financing rates but instead are adding to inflation risk (or at least inflation fear). After the Fed’s September 2024 cut that began the easing cycle, the 10-year yield rose materially (45bps as of the time of this article), with term premium causing long yields to rise even when the policy rate falls.

- The Fed’s internal split is more consistent with a 2026 pause. On December 10, 2025, the Fed cut again, bringing the fed funds target range to 3.5%–3.75%, but the vote and projections indicated “late-cycle disagreement.” Fed officials appear split between those worried inflation is still too high and those focused on labor-market softening, calling the dual mandate “in tension,” and observing that the cut “may be the last expected move…for a while.” The December decision included three dissents, the most since 2019. Beyond the formal dissents, there were six participants whose projections implied no cut was necessary. The Fed’s median expectation for 2026 remained just one cut, but the range of views is wide, with projected end-2026 rates varying significantly, thus a meaningful group of participants effectively signaled that easing has gone far enough. When a committee looks like this (cuts continuing mechanically, but disagreement rising) the future path of least resistance is often inaction until the data force a decision. The Fed is setting up an institutional posture for a pause, and pauses are when hikes become possible, because the committee is no longer psychologically anchored to a cutting cycle.

- The neutral rate may be higher than we used to think. Economists argue that the neutral rate of interest (r*) has drifted up for two reasons: larger budget deficits and the AI/data center investment boom, both of which push up long-term rates. To this point, Powell said policy is already “within a range of plausible estimate of neutral,” and further normalization would be about stabilizing the labor market while letting inflation drift toward target. By most expert judgment, neutral is widely assumed to be about 3%, implying that a single additional cut would bring policy close to neutral without tipping into a more accommodative stance. If the policy rate is near neutral, the hurdle for further cuts gets higher. If the economy is not faltering and especially if growth is being revised upward (as the Fed did for 2026) then cutting from “near neutral” toward “accommodative” is effectively a bet that inflation will keep cooling on its own.

- There is a compelling argument against the comforting narrative that “once tariff effects fade, inflation fades.” If goods inflation has deeper roots – inventory cycles, reshoring costs, commodity pass-through, tighter labor supply in logistics/manufacturing – then inflation can remain sticky even if shelter cools and wages moderate. Core goods prices started rising in mid-2024 and had nothing at all to do with tariffs. If the risk is that inflation continues to surprise to the upside, the Fed is unlikely to cut interest rates. The New York Fed’s DSGE model update adds another dimension: it explicitly says inflation projections are higher in 2025 because of cost-push shocks capturing the effects of tariffs, while also noting stronger growth in 2025 driven partly by a lower projected policy-rate path and higher productivity. If 2026 demonstrates higher inflation or inflation expectations, the Fed will be biased toward holding.

- Term premia means the added yield that investors demand for holding long-duration bonds when inflation uncertainty, supply risk, or policy credibility risk rises. Term premia removes “left tail” recession risk and creates more “right tail” inflation risk, leading investors to raise term premia. Government deficits also push upward on long rates. If the Treasury market demands higher term premia (because of deficits, issuance, inflation uncertainty, or perceived political risk to Fed independence), then the Fed can cut and still fail to deliver lower mortgage rates, lower corporate yields, or sustained easing in the real economy. At that point, more cuts become less attractive. The Fed risks “pushing on a string” while simultaneously giving inflation room to reawaken.

- The AI/data center boom is macro-relevant, and it can be inflationary in the short run. In the last two years “AI” stopped being a tech story and became a macro story, because investment spending is large enough to move markets and economic conditions, and to strain real resources (power, construction labor, specialized equipment). By most estimates, data center and AI-related investments accounted for 75 to 85% of U.S. private domestic demand growth in the first half of 2025. If that boom continues into 2026, it can raise trend productivity over time, but it can also increase near-term inflation pressure through construction capacity constraints, wage pressure in skilled trades, higher electricity demand and grid investment costs, and supply bottlenecks in chips, cooling, and power equipment. This is the “Goldilocks trap”: the same investment boom that supports growth can also keep the economy running hot enough that the Fed cannot safely ease.

- Fed leadership change and perceived independence risk raises the bar for cuts. Even if you think politics should not affect monetary policy, markets price what they believe. Here’s how this connects to a hold-or-hike thesis: a) If the market fears political influence will bias the Fed dovish, term premia can rise (investors demand compensation for future inflation/credibility risk); b) Rising term premia tighten financial conditions through higher long rates, even without Fed hikes; c) The Fed, seeking to defend credibility and anchor inflation expectations, may respond by not cutting, but hiking if inflation pressures persist. Paradoxically, pressure for cuts can produce the opposite outcome if it undermines credibility.

- While the Fed’s dots show one cut next year, those same dots also show dispersion and fragility. Multiple officials indicated no cuts next year, and the committee is divided with end-2026 range that spans 2-4%. The dot plot is not a promise but snapshot of conditional thinking. When the distribution widens, it is often a sign that the Fed is approaching a regime where the next move is data-dependent and less predictable—which is exactly when “hold” becomes the default and “hike” re-enters the plausible set.

- The Fed announced it would buy $40 billion of short-term bills monthly to stabilize funding markets and keep the policy rate within its range – an action some participants viewed as “stealth easing.” These liquidity operations can substitute for rate cuts and raise the bar for more cuts. If the Fed is providing liquidity support through balance-sheet tools (even if framed as technical), it reduces the urgency to cut rates further. And if risk assets rally on that liquidity, the Fed may worry that broader financial conditions are easing too much, thus providing another reason to hold or even lean hawkish.

Conclusion

There are sound reasons why market conditions can cause the Fed’s next rate move to be neutral, or even a hike in 2026. Sticky inflation, rising term premium, fiscal/structural demand, and credibility risk are clearly present in the data. If 2026 turns out to be a year where inflation simply refuses to glide to 2% or where growth re-accelerates on investment and fiscal impulse, the Fed’s most likely posture is not “keep cutting.” Instead, it is hold and prepared to hike if inflation forces the issue. Borrowers and lenders who are factoring 100% probability of continued interest rate decreases in 2026 may be surprised.