Stablecoin: What Bank Executives Need to Know

For years, cross-border payments have been slow, expensive, and opaque. On top of that, currencies and currency transactions have often lacked trust. A stablecoin promise a faster, more transparent and trustworthy solution. With the signing of the Genius Act into law, banks have the rare chance to rethink how they move money, store value and manage liquidity. This article will break down what stablecoins are, why they matter to banks, and what strategies bankers should consider moving forward.

Executive Summary

- The Act: The GENIUS Act now enables banks to issue stablecoin backed 1:1 with permissible investments in a reserve account.

- Capital Treatment: Stablecoin reserves are off-balance sheet liabilities held in a subsidiary of the operating company, are not liabilities of the bank and do not (presently) require capital.

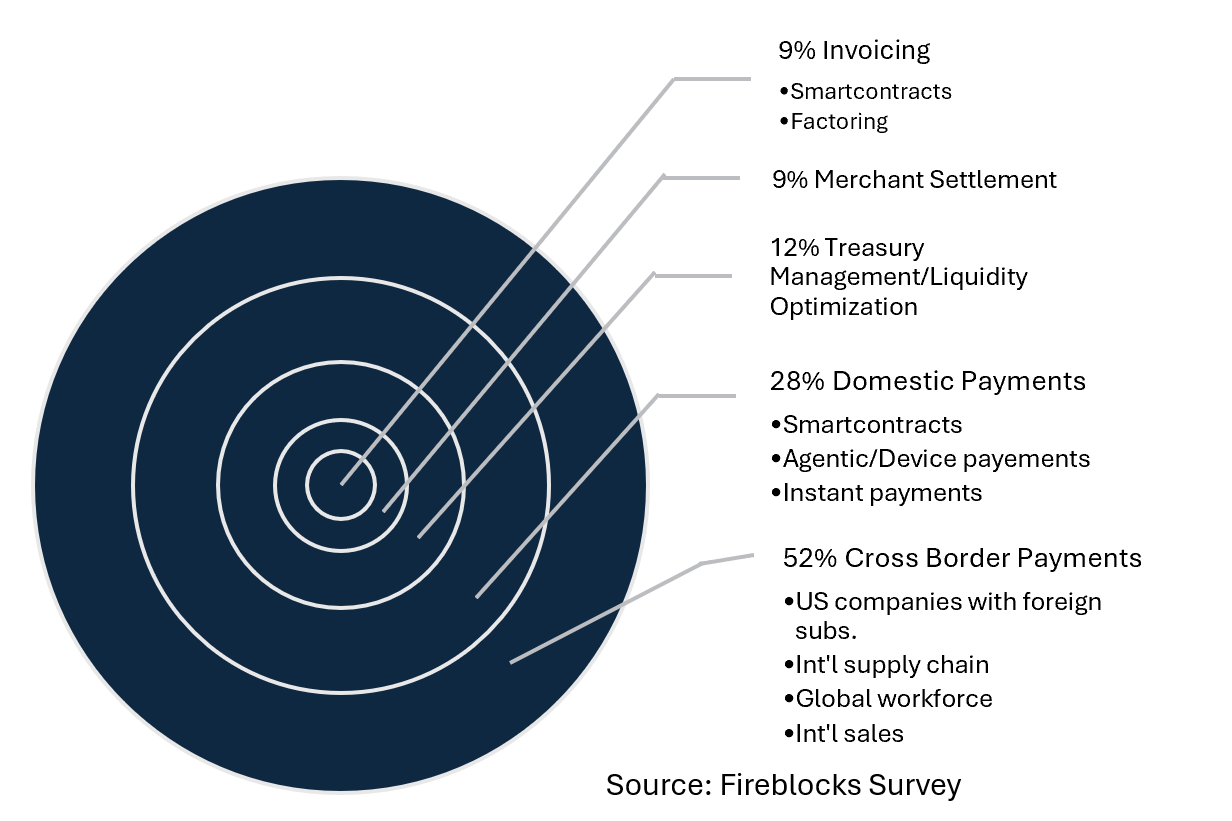

- Use Case: The primary use case revolves around enabling cross-border transactions for customers while arbitraging investment returns and potentially generating fees. The second major use case will arise around domestic payments as stablecoin can be owned by agents and devices.

- Main Risks: Customers and banks will need to judge the quality of the issuing institution, its duration/liquidity of its reserve holdings, audit quality, and the quality of the underlying blockchain to limit reputational risk, achieve full interoperability and maximize liquidity within a risk framework.

- Timing: Banks can issue stablecoin immediately (and some already have) but must comply with the Act and subsequent regulations by the earlier of 1/18/27, or 120 days after implemented Federal regulation.

The conversation of stablecoins in finance is no longer theoretical for most community banks as the technology has existed for more than a decade as this month marks the 11th anniversary of BitUSD. However, the GENIUS Act has now given financial institutions, fintechs and regulators the starting framework to modernize finance.

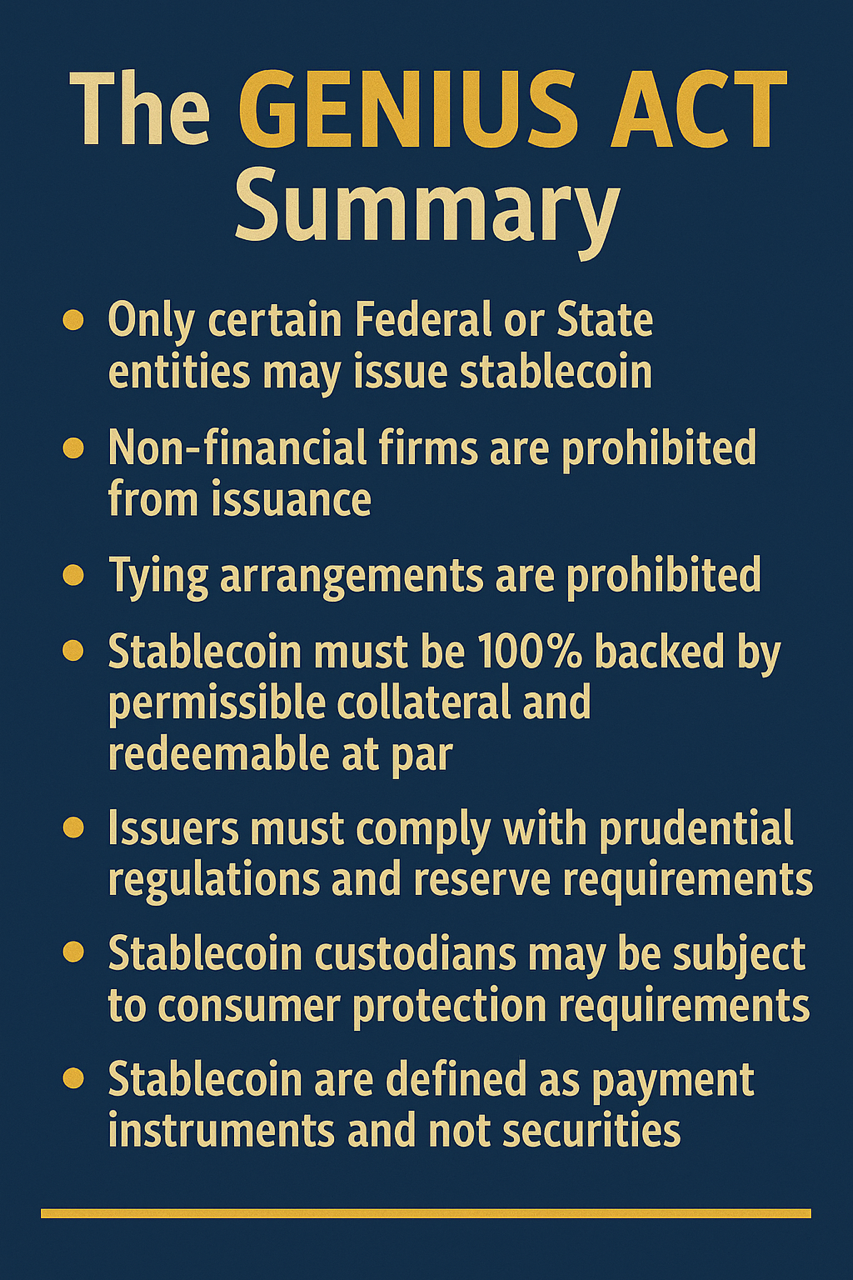

Summary of The GENIUS Act

The “Guiding and Establishing National Innovation for U.S. Stablecoin” (GENIUS) Act was signed into law on July 18, 2025. The Act marks the first major crypto legislation in the U.S. and creates licensing and regulatory requirements for domestic payment stablecoin issuers and standards for participation in the market by foreign stablecoin issuers. The Act also sets forth the custody and safekeeping of “Reserves,” or assets that back any given stablecoin issuance.

The Act goes on to establish the authority of the regulators within this domain that includes the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, the OCC, the NCUA, and State payment stablecoin regulators (the relevant State agency with primary regulatory and supervisory authority). These regulators will presumably issue interagency guidance or a joint statement detailing the minimum capital, liquidity and risk management required to issue in addition to more granular details around reserve collateral management. These regulators will also create a federal application process.

In a nutshell, the GENIUS Act sets clearer guidelines for the issuance and management of stablecoins in the U.S. and provides a clearer legal framework for offering stablecoin products. This means banks could potentially issue their own stablecoins or partner with fintech providers to integrate stablecoin rails into existing payment infrastructure.

The Act is effective the earlier of January 18, 2027, or a date that is 120 days after the date on which the Federal regulators implement regulations. After that date only those entities authorized under the Act can issue a payment stablecoin in the U.S.

What Are Stablecoins?

With the passage of the Act, stablecoins are now defined as a digital asset, in tokenized form, which is designed to be used as a means of payment or settlement. Issuers of stablecoins are obligated to redeem or repurchase at the fixed value of the underlying fiat currency. For the sake of regulation and legal standing, it is important to note that stablecoins are not a deposit, do not carry FDIC insurance coverage and are not securities under federal laws.

One defining difference is, like currency and unlike a deposit, stablecoins can exist outside the banking system. Each issued stablecoin is a digital representation of value cryptographically recorded on a blockchain that serves as a secure, and immutable, “distributed ledger.” This is a major distinction that banks must understand in that once issued, it is no longer a bank verifying value or a payment transaction as all transfers of value are done on a public digital ledger where transactions are independently verified and settled using cryptography to maintain the integrity of the ledger. Up to this point in banking history, a bank had to have an account of the person or company holding the asset or liability. This is now no longer the case.

This is to say that a stablecoin is issued from a bank into a digital wallet of the customer. Instead of using an internal database such as a bank’s core system to record stablecoin ownership, ownership information is now stored away from the bank on an immutable blockchain and reflected in the customer’s wallet.

The blockchain, in essence, now becomes the customer’s “core system” of record and a bank is no longer needed to transfer value. The value exists in the stablecoin itself and can be turned back into fiat currency at any time by redeeming from the issuing bank or by any bank willing to honor the specific stablecoin.

This means that once a bank’s stablecoin is out there in the public, banks have little control over what the coin is used for and who holds it. The coin may be redeemed immediately by the original owner, it may be transferred 100,000 times and then redeemed, or the stablecoin may never be redeemed.

From a customer’s point of view, ownership is now never in question and can be verified 24/7/365 simply by looking at their wallet.

The Big Unlock – Stablecoin Ownership

The other major implication of a stablecoin is ownership. Up to this point in mankind’s history, a human has always been required to validate ownership of value and has had to effect a transaction. Now, a stablecoin can be held by a person, a corporation, a device, or a robotic agent. This is one of the big “unlocks.”

Stablecoins can now be purchased by an agentic agent or by a device and held without a human. Agents and devices can now use the stablecoin to carry out its mission whether this means purchasing shoes on behalf of a human or part of a factory reordering steel. The result is more efficient and liquid commerce on a global scale.

Risk 1: What Backs a Stablecoin?

While there are several types of stablecoins, for the sake of banking and the GENIUS Act, stablecoins are a type of cryptocurrency that attempt to maintain a stable value by pegging itself to a specific liquid asset. Typically, the referenced asset is a fiat currency, the goal of which is to limit the frequent volatility associated with traditional cryptocurrencies.

Banks will need to form a subsidiary of the operating company and need to get their stablecoin approved as a federally qualified stablecoin issue or a state-qualified payment stablecoin issue.

To ensure the stablecoin keeps its value or what is known as a “peg,” issuers collateralize the coin on a 1:1 basis with the fiat currency or permissible asset.

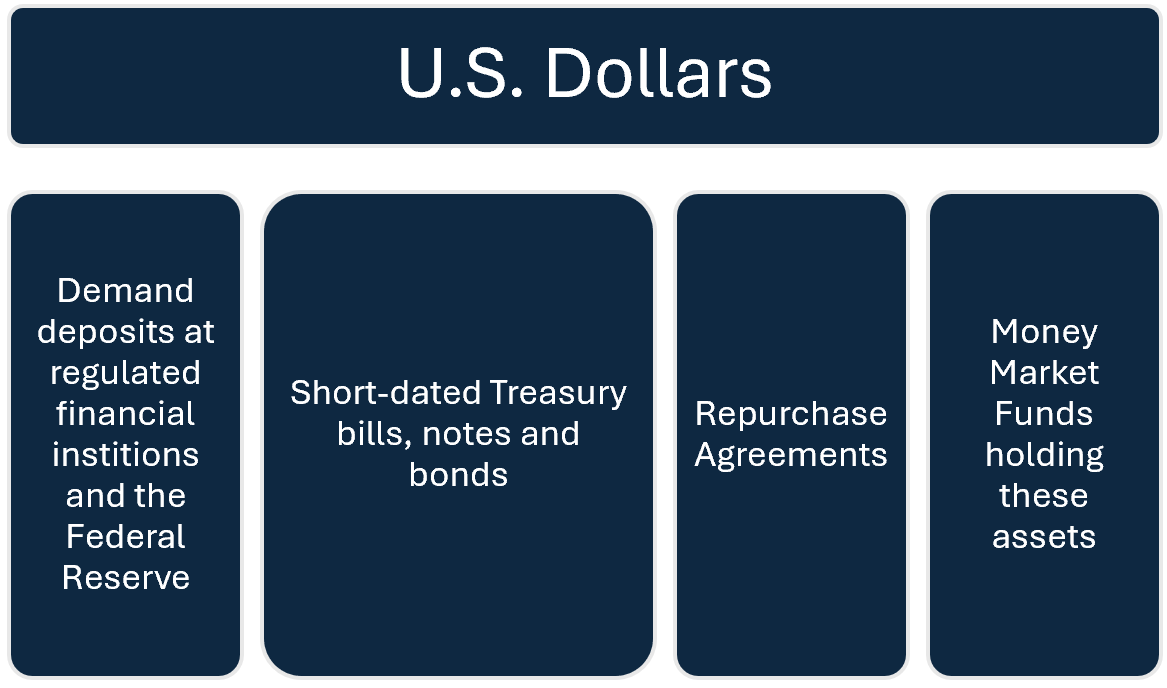

Permissible assets for banks include the following in a segregated account:

This reserve account will have monthly disclosures and if over $50Bn, will be subject to an annual audit.

While having these permissible investments backing a stablecoin mitigates much of the market risk there remains a healthy amount of residual risk. One risk is that each institution will have a different mix of assets and a different duration on the portfolio. Some banks will choose to hold all U.S. dollars in their reserve accounts while others will have the maximum amount of Treasury exposure at the longest duration. In times of extreme interest rate movement combined with significant redemption, issuing banks could be forced to sell treasuries at a loss to meet liquidity demands and could potentially have a value below a dollar. The second risk is the stability of the issuing institution. Should an issuing bank have a liquidity run or become insolvent, then stablecoin holders may sell below the coin’s par value as stablecoin redemptions are halted.

This infamously happened to Circle during the Silicon Valley Bank failure back on March 11, 2023, when Circle disclosed that it had $3.3B, or 8% of its reserves, on deposit at SVB. The ensuing panic sent Circle’s stablecoin down to 87 cents.

Risk 2: The Business Case for a Bank Stablecoin

A key benefit of stablecoins are the increased stability and speed of payment transactions. While domestic payments will benefit from a stablecoin, it will be largely on the edge cases given the advent of instant payments. Transactions over $10mm, the current limit on the instant payment rails, may benefit from a stablecoin transaction, as well commerce by non-humans as previously discussed. There is also the ability to program payments in what is called a “smart contract” that we will cover in the future, but it will be years before these attributes compose a significant use case for stablecoin.

That said, the most immediate use case for stablecoin is when it comes to cross-border transactions.

Traditional international transactions often require wire transfers via the involvement of correspondent banks, nostra accounts and communication services. While effective, this process is cumbersome, as it requires multiple institutions, and is not internet based. These issues become further pronounced when transacting with emerging markets. This is where the advantages of stablecoin transactions shine. Stablecoins present a compelling alternative to traditional payment messaging systems like SWIFT, CHIPS, and Fedwire by offering settlement times measured in minutes, lower transaction costs, and enhanced transparency.

Unlike SWIFT, which is a global messaging network rather than a settlement system, stablecoins carry both the value and the message which can enable near-instant value transfer across borders without reliance on intermediaries. While real-time services such as CHIPS and Fedwire may offer secure, high-value domestic transfers, they operate within banking hours and come with relatively high fees and settlements delays. Stablecoins in global finance, however, can settle transactions 24/7/365 through permissioned or regulated blockchains.

Stablecoins also improve the cost efficiency of international transactions, creating a convincing reason for the implementation of the tool. An advantage of stablecoins is that transactions conducted on the blockchain avoid typical banking fees. This benefit does not stop at the institutional level but can assist small vendors and suppliers that frequently make payments across borders.

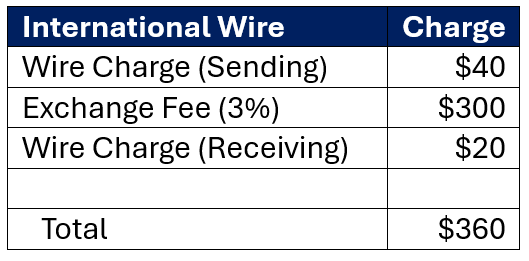

Let us show a comparison for a $10,000 international wire from the U.S. to Mexico.

This turns out to be 3.6%, a percentage that obviously goes down as transaction size gets larger but for a $200k transaction, it is still a healthy 28 basis points. For smaller transactions, it gets much worse as retail remittances are around 6% and credit card charges are close to 3%.

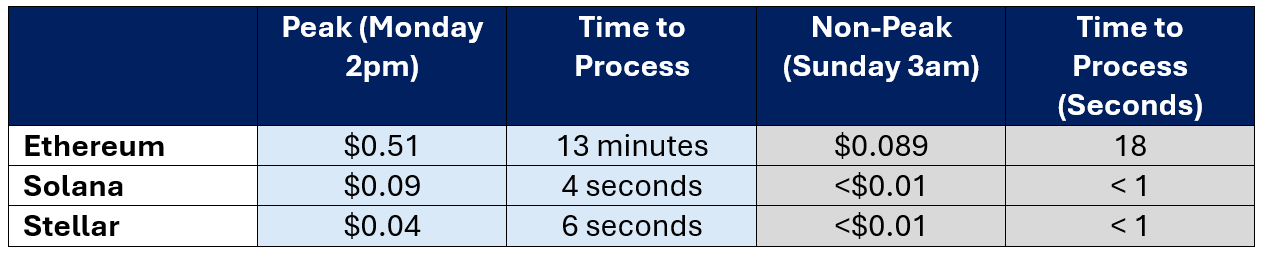

While from a payments perspective, stablecoins offer faster settlement times compared to legacy systems like SWIFT and CHIPS, it is not without its costs. When evaluating stablecoin usages for cross border payment solutions, an important factor to consider is blockchain “gas” or fees. Gas is the transaction fee paid to the blockchain network to compensate validators for processing and validating transactions. They are calculated based on the amount of computational effort, or “gas,” required to validate a transaction. The unfortunate thing is that this gas is based on demand for blockchain resources and so can vary based on time and complexity of the transaction. For each transfer of ownership of a stablecoin, there are a minimum of 17 variables describing the state and ownership of the transaction that needs to be written to the chain. At the time of this writing, this breaks down to the following average costs:

In addition to these transaction costs, banks will have additional infrastructure fees for their modern core system, issuing costs and wallet costs. This is in addition to FX costs that an issuing bank will also have to absorb.

At present, most banks breakeven on the sending and receiving of international wires (including the fraud and compliance cost), thus most of the profit is made on foreign exchange fees and operating balances kept in transaction accounts to support cross-border transactions. Depending on volume, blockchain and cost structure, a stablecoin is estimated to cost a bank about $0.39 per transaction on average.

As it is with traditional international wire transactions, offsetting this cost of stablecoin are also the foreign exchange fees, the value of the deposits and any fees that can be charged.

When it comes to fees, retail fees from entities like PayPal and Coinbase are free. Institutional fees for stablecoin have yet to be formally set. Because of the much lower cost structure of stablecoin, it is contemplated by most institutions to include stablecoin in the analysis fees for treasury management and charging a mark-up for their fintech customers to manage the payments and risk.

Given these economics, the business case comes down to how many international customers a bank touches or the number of U.S. customers a bank has that either has a revenue stream or a supply chain cost in a foreign currency. Because of the cheaper and faster cost structure, many banks are contemplating giving their stablecoin away for free as well as managing the issuance for their larger corporate customers (often called the “corporate coin” business). In exchange, a bank would make their money off the float of the stablecoin reserves.

A mid-sized community bank may be able to issue $1B in stablecoin float for its corporate, middle market and retail clients for a current value of $40mm per year assuming a 4% spread in addition to any fees it might be able to garner. This would be an off-balance sheet item, so no capital reserves are needed. Assuming a legal, compliance, technology, and overhead cost of starting a stablecoin platform at $1.2mm amortized over five years plus a $1mm per year of incremental operating cost, that is a 32x investment return.

At this level of investment, and assuming a conservative 1% reduction in funding cost for banks, this puts the breakeven at a mere $41mm of stablecoin issuance or well within the reaches for even a $1B asset-sized bank.

From a business model standpoint, as long as you have customers handling international business, the business case risk is minimized.

Of course, there are some more risks that should be highlighted.

Risk 3: The Risk of the Blockchain

One underappreciated risk is that to the underlying technology stack that powers the coin. Each blockchain has its own trade-offs and limitations. Ethereum, Solana, Stellar, Avalanche, Algorand and Polygon are some of the blockchains often considered for bank issuance. Solana features ultra-low fees and some of the fastest processing times, it is a relatively new stack. This means that their performance record is not as longstanding and robust as some of the older chains, which may cause investors to question their ability to scale and integrate. Ethereum, on the other hand, is the most commonly used, has the most nodes (validators), is the most tested and has the most relative transparency due to the many third-parties that monitor the chain. However, where Ethereum excels in integration and performance, it lacks cost effectiveness and often processing times. Circle’s USDC was built on Ethereum while Tether’s USDT utilizes a multi-chain approach using Ethereum as its main ledger and smart contract enablement, Tron for processing speed plus Bitcoin (via the Omni Layer), Algorand, Avalanche, EOS, Solana and the Liquid Network for interoperability.

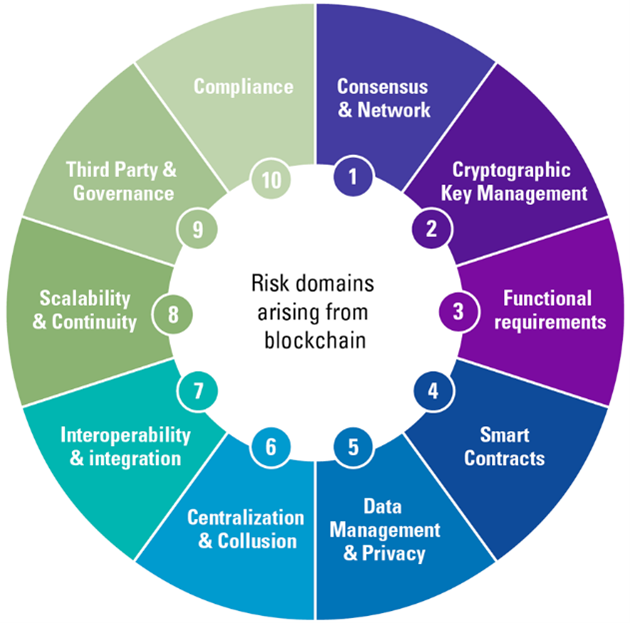

Banks will either need to choose an existing stablecoin to provide for their customers or create their own. Regardless of the choice, paying attention to the quality and capabilities of the blockchain (below) will be required for prudent risk management.

Risk 4: Stablecoin Regulatory Risk

Finally, regulatory compliance is mandatory in cross border payments regardless of payment method. As such, stablecoin offers no exception. Banks face customer due diligence requirements such as KYC, AML and fraud screening, as well as transaction monitoring/reporting when sending or receiving stablecoins.

Understanding the identity of those customers that want to create the stablecoin (called “minting”) or redeem the stablecoin (called “burning”) will likely need to undergo some identity validation. However, one critical distinction is that once issued, a customer is free to transact business with any party away from the bank with no liability back to the bank until the stablecoin is redeemed.

Another critical aspect in the risk of stablecoin is unlike currency and many payment instruments, every step of a stablecoin’s journey can be tracked not only making every payment traceable and auditable but also can provide a treasure trove of real-time data to better inform banks around fraud and bad actors.

Depending on jurisdiction and transaction size, banks may also need to comply with local country requirements such as transaction and tax reporting.

Risk 5: The Stablecoin Off-ramp Problem

For a bank to be successful in stablecoin issuance, it will need to develop a network of international receiving banks that can turn its stablecoin into the local fiat currency should it be needed. Banks will need to be able to develop the network on their own or use an existing network such as Circle’s CPN.

Conversely, issuing banks will likely also need to facilitate stablecoin redemption from other banks both from customers and non-customers requiring the infrastructure and compliance to handle this efficiently.

Risk 6: Implementation Challenges

The implementation of infrastructure for stablecoin in global finance is not just a plug-and-play process. It often requires banks to build entirely new ledger systems alongside their existing cores. Traditional banking systems were not designed to accommodate tokenized assets or 24/7/365 international settlement. To manage stablecoins, plus potential tokenized deposits in the future, banks may need to run multiple synchronized ledgers or invest in a new “modern core.” This transformation involves not only upfront technology costs, but also long-term maintenance, staffing, and regulatory alignment. For banks, the business case for stablecoin adoption must outweigh these infrastructure burdens, which are currently only feasible in high-volume, high-friction use cases, namely, cross-border and agentic payments.

This complexity also exists within compliance. While blockchains allow for transparent tracking, the need to monitor multiple chains with different standards put pressure on compliance teams. Firms must ask how many protocols their risk departments can realistically oversee.

Are Stablecoins the Future of Global Payments?

To effectively improve cross-border and domestic payments, stablecoin addresses areas where traditional banking and payment systems fall short. Given their inherent stability and increasing adoption, stablecoins in finance offer a compelling solution for streamlining transactions and expanding access to financial services. While a different risk profile and infrastructural burdens exist, the potential opportunity is substantial.

The GENIUS Act was a watershed moment in banking. There are now clear boundaries for issuer eligibility, strict prudential and consumer protection standards, and a dual state-federal supervisory pathway for banks to issue. The Act now provides a robust and durable regulatory and supervisory structure that will further be enhanced in the near future that can foster innovation in stablecoin technology.

In the future, we will go deeper into the various aspects of stablecoin and will detail how tokenized deposits should be considered as well due to the complimentary nature of the product.

- Co-authored by Richard Mitchell