The Perils of Interest Rate Risk in Loan Pricing

Banks often lose 5% of a loan’s value before a loan is even booked due to interest rate risk in loan pricing. Persistently high inflation and the unknowns in the new administration’s implementation of stated policies have translated to rapid increases in long-term interest rates. In a period of rapid change (or high volatility), we see some banks fall into a trap of mispricing their commercial loans. The mistake involves holding interest rates constant from term sheet to loan closing, and some banks have seen over 100bps net interest margin (NIM) erosion just from this misprice alone.

Rapid Market Movement Means Greater Interest Rate Risk in Loan Pricing

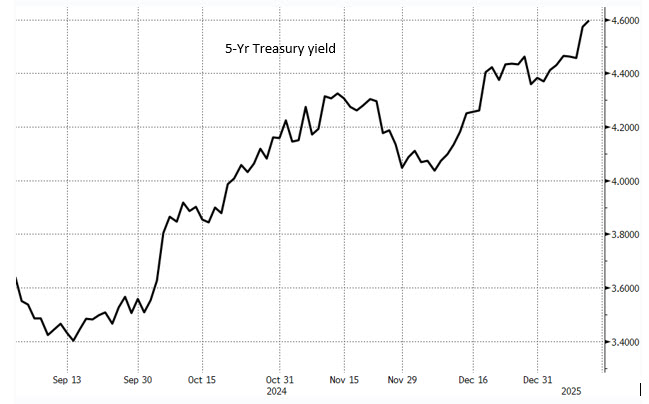

During periods of rapid interest rate changes, some banks find themselves pricing off-market. Some banks have a policy of honoring loan rates that they quote for three months to closing. This behavior has many negative implications for banks. The graph below shows five-year Treasury yield from September to mid-January. Over this period, the five-year yield has increased 120bps.

By holding a fixed-rate loan when longer-term rates are rising, lenders are effectively decreasing their expected NIM over the life of that loan. The only way to avoid this compression between the start of the loan closing cycle and loan booking is to quote the loan as a spread over an index, even if that loan is not meant to be hedged or sold in the market.

Consider a loan where the bank issued a term sheet in September and the loan closed in December of 2024. The loan was quoted on a fixed rate of 6.875% in the term sheet and the bank assumed an implied 3.50% spread to the five-year Treasury. When that loan closed in December, the five-year Treasury yield had risen by 1.01%, and the bank’s implied spread was only 2.49% over the 5-year Treasury. The bank would not originate loans at 2.49% over the Treasury index, but that is effectively what transpired. This bank’s NIM is expected to be 101bps lower over the life of that asset. However, this concession from the bank is not necessary and easily avoidable.

Some bankers will argue that interest rates are as likely to fall as to rise, and overall, the bank is neutral because some loans will close when rates are falling, and the bank will realize a higher NIM. But there are two major flaws with this argument. First, we are witnessing a pervasive rising interest rate environment, and waiting for rates to ebb can be very painful for many banks. Second, and most importantly, if interest rates do fall between acceptance of the term sheet and loan closing, the average borrower would not accept their initially quoted rate. While some borrowers are rate insensitive, those borrowers are rare and typically do not represent the borrower that many banks target. Most borrowers are more sophisticated and will ask the bank to reprice a loan when market rates decline. This is a free option that banks are giving away to their borrowers.

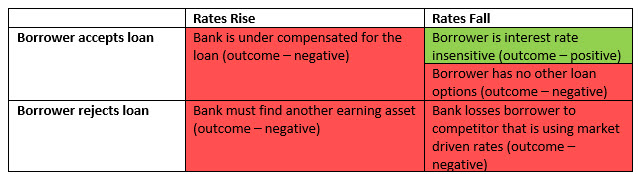

The table below describes the four possible scenarios where the bank does not reprice a loan to market, and rates rise or fall, and the borrower accepts or rejects a loan. By not adjusting pricing to reflect market-driven interest rate movement, a bank is almost always diluting value. The only way a bank creates value is under the assumption that the borrower is not aware of interest rate movement or is price insensitive. While this scenario may occur some of the time, it cannot occur frequently enough to build a business model and sustain a loan portfolio. Every other outcome for the bank is negative. The table below shows a color-coded outcome for the bank (green – positive and red – negative).

In summary, a bank is almost always in an inferior position by not re-quoting the loan rate with market movement.

Conclusion

By analyzing the possible scenario outcomes for the bank, we conclude that banks are better off by adjusting their pricing to an index that moves with interest rate volatility. This methodology reduces the interest rate risk in loan pricing. We believe that banks must adjust their rate quotes to reflect daily volatility up to the date that the loan is booked. Of course, the savvy banker will point out that requoting the loan to a spread over an index to closing only eliminates interest rate risk for a few months. Once the loan is booked, the loan credit spread is unknown since a bank’s cost of funding is short-term and will move with short-term rates. We agree that banks should not take interest rate risk without compensation – this relates to setting loan rates in advance of closing and maintaining fixed-rate loans where borrowers maintain an option to prepay when rates drop, and borrowers are motivated to extend loan duration when interest rates rise.