The Risk of The Main Street Lending Program By The Numbers

What is with all the waving we do at the end of Zoom calls? Should we start waving as we back out of the room for in-person meetings in the future? By the same token, many banks are baffled by what to do with the Main Street Lending Program (MSLP), as this is not something we would do in normal times. Yet, we found ourselves both participating and waiving at the end of those MSLP Zoom calls. No matter if your bank is going to participate in MSLP or not, understanding the risk involved is a master class in loan structuring and credit. The Goldilocks nature of the Program has presented challenges for the Treasury, banks, and borrowers alike. In this article, we break down the credit risk, look at profitability, and then propose a strategy to follow.

The Goldilocks Loan

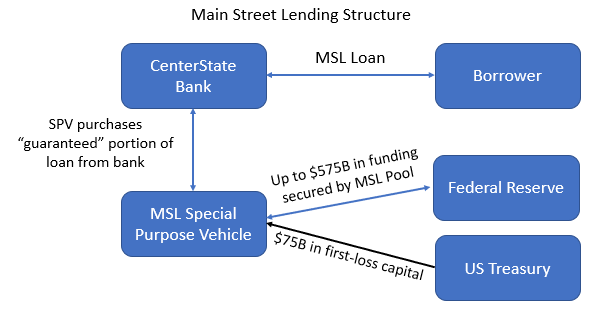

As you have undoubtedly heard, the $600 billion MSLP is composed of five different facilities and targets bringing relief capital to those businesses that were too large to access the Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) but not a national corporation with access to the public markets or the PMCCF Program. While small business is a community bank’s bread and butter customer, it is the large small business and mid-sized business that likely compose the greatest risk at the bank. As such, on paper, MSLP appears essential for not only bringing corporate America relief but also protecting the balance sheets of banks.

However, there is a marketing issue to start. While banks only retain 5% of the exposure, they must underwrite the loan as if they were going to take 100% of the exposure but using 2019 financial and operating data and 2020 liquidity data. That aspect alone is a sizeable challenge and places a credit quality floor on what companies a bank can underwrite.

On the other side of the coin, the Program comes with prohibitions on repaying other debt, a good faith commitment to maintaining payroll plus restrictions on compensation, stock repurchases, and dividends. While these restrictions are understandable, it places a credit quality ceiling on what companies apply for the program.

As a result of the requirements alone, a company has to be strong enough to pass underwriting but weak enough not to qualify for a conventional or SBA 7(a) loan where a borrower would not have to put up with the array of MSLP restrictions. As a result, supply is restricted, and demand is limited.

Given the complications of the program, a bank needs to devote a slug of resources to the Program, which is difficult to justify with limited upside. Unfortunately, that is the easiest decision to make, as the math gets harder when you consider the actual risk.

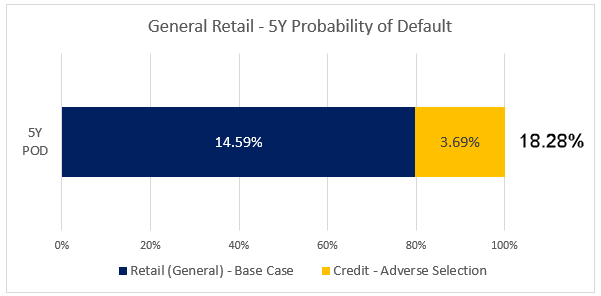

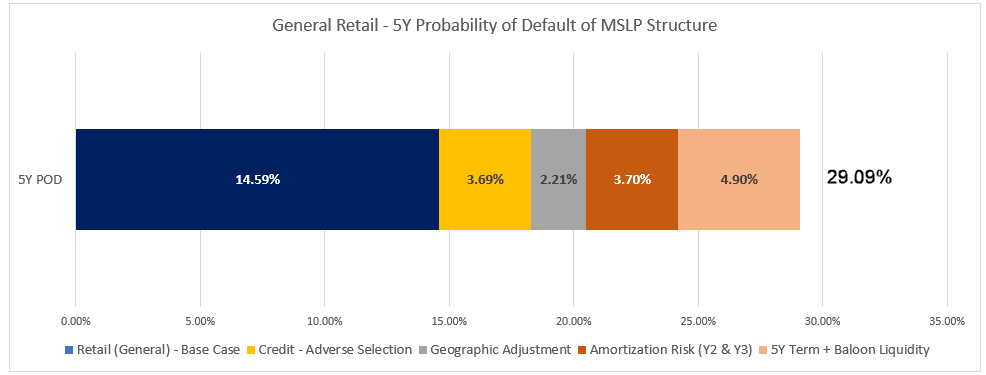

Credit Risk – The Base Case With Current Credit Shock

Let’s start by taking a sample industry that is not too impacted, such as transportation, sports, movie, or even a restaurant. Let’s take an industry in the middle of a credit spectrum, such as a small retail chain. Here, the five-year probability of default (POD) is a substantial 14.59%. This takes into account the current COVID-19 environment and can be used for a proxy of a wide range of retail establishments on your balance sheet since many sub-sectors such as bakeries, clothing stores, sporting goods stores, jewelry, housewares, hardware, furniture, and even convenience stores are all pretty close to that POD.

For context, those same industries had a five-year cumulative probability of default of around 4% to 6% back in January.

Credit Risk – Adverse Selection

The problem then arises that you are not getting the average credit in each sector, because of the structure of the program mentioned above, banks are getting the credit that is not strong enough for conventional financing. These riskier credits not only present more of a credit risk now, but they are likely more volatile than the average credit, so that is an additional risk for banks over time. The combination of higher current credit risk and potentially higher future credit risk adds about another 25% of risk to the bank moving the five-year probability of default for the average credit up to 18.28%.

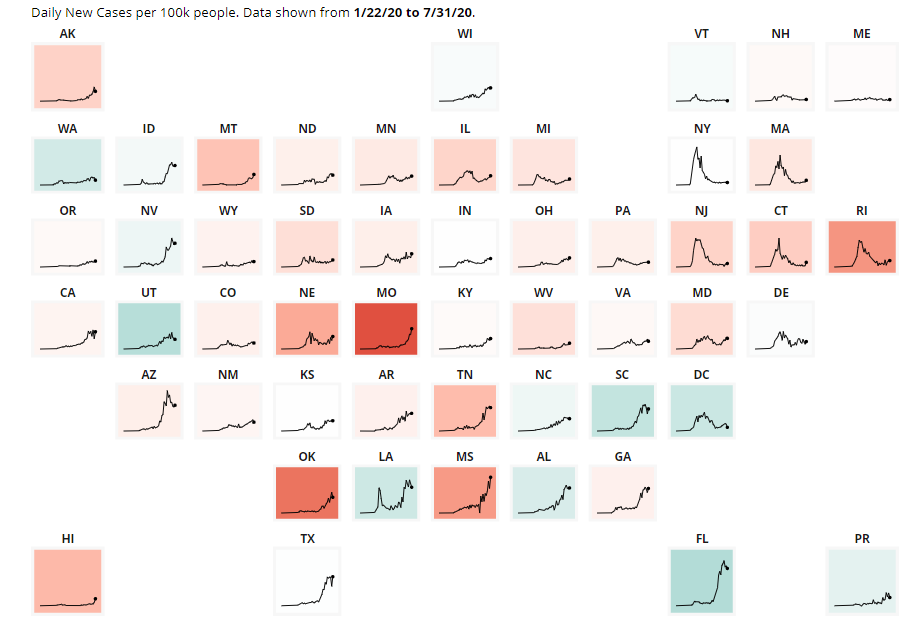

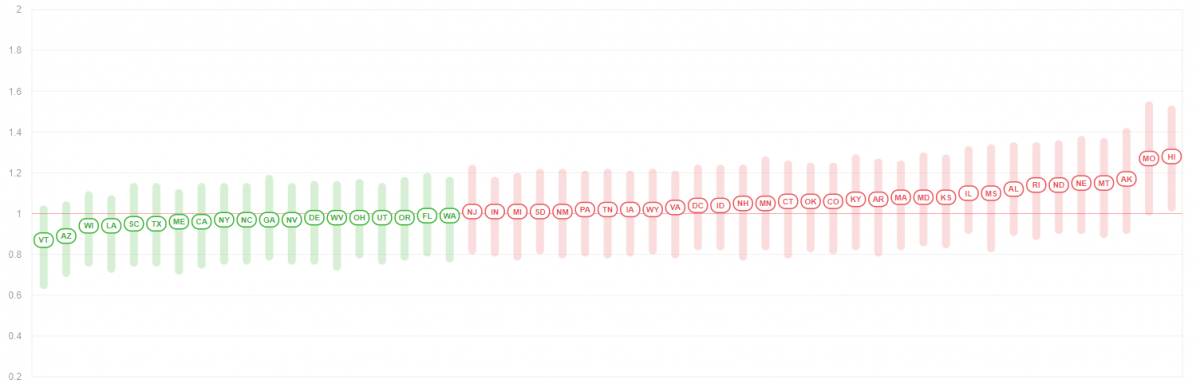

Credit Risk – Geography

In good times, geographies tend to converge as it relates to credit risk. However, in times of a credit shock, earnings volatility increases, and location matters. In times of a credit shock coupled with geographic restrictions such as a natural disaster or a pandemic, your location matters even more. If your retail borrower is located in one of the hard-hit counties in Missouri, credit risk is about 35% higher than if your borrower was located in a major county in Vermont. As mentioned in our previous articles, our credit model uses a combination of foot traffic, current cases, 3-day new case trends, and new deaths (using the John Hopkins data), and rate of transmission (data sourced from covidtracking.com and compiled by rt.live).

Certain counties in states like Vermont, New York (ironically), South Carolina, Wisconsin, and others present a minimal geographical risk because of their control efforts and path to reopening (for the moment). Conversely, counties within Hawaii, Missouri, Nebraska, Alabama, Alaska, and others, present a higher level of risk because of their trend. On average, if you are in a state or county with a consistent historical transmission rate (Rnaught) greater than “1” such as MN, CT, OK, and CO, the additional impact to the probability of default over five-years is about 12%.

Structure Risk – The 5Y Problem

The MSLP is structured as a five-year full amortizing loan. This is the start of the realization that when they put the Program together, the Fed was more influenced by investment bankers than commercial lenders or credit administrators. While this varies from business to business, as a rule of thumb, you seldom want to offer any borrower a five-year loan and hardly ever want to provide a five-year loan in times of credit stress.

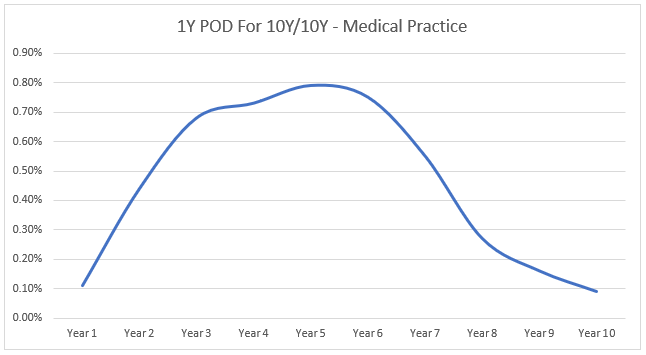

Without a pandemic going on, below is a graph of the one-year probabilities of defaults for a ten-year, fully amortizing loan. As can be seen in this particular case using a multi-doctor medical practice loan secured by real estate, credit risk usually peaks between years four and seven with the average right around year five. When bankers first make a loan, both credit risk and earnings variability are low during the first year. However, after Year One, credit risk rises sharply as more uncertainty with both the business and the economy creep into the cash flow.

If this is the profile of your average borrower, then creating a maturity in Year Five is the last thing you want to do as that is when the probability of default is likely the highest. Usually, after year six, appreciation of the business or property, combined with amortization and a history of payment, usually results in a rapidly declining probability of default. Once you get to Year Eight, the borrower is usually always compelled to make the debt service payment as their risk is starkly asymmetrical. If they don’t make the relatively small debt service payments to the bank, they may lose their entire business or property.

Because the MSLP only utilizes a five-year term, loan structuring risk is introduced, further elevating the probability of default.

Structuring Risk – Amortization, Balloon Payments, and Liquidity Risk

The other problem with the MSLP structure is the amortization schedule. While seemingly benign on paper, it further exacerbates credit risk due to its structure. Consider that the Program has an unusual structure of required principal paydowns – 0%, 0%, 15%, 15%, and 70%.

Here, few businesses that seek MSLP loans currently have the cash flow this year to start to accrue the principal needed to meet the first paydown in Year Three. Depending on the industry, the more likely scenario is that normal cash flow would not resume until late 2022, which is all predicated on the fact that a widely distributed vaccine will be available come to the end of 1Q and be distributed in 2Q. Assuming a six month stabilization period, that gives most businesses 12 months to accrue two, successive 15% paydown periods. That is a large load for even a healthy business let alone one that was weak enough to have to apply to MSLP in the first place.

However, that 15% amortization is the least of everyone’s problems. The most problematic aspect of this Program is the fact that the Federal Reserve combined a five-year term with a 70% balloon structure. With little or no current cash flow, banks (and borrowers) must place a bet on either the Program being extended or cash flow coming back enough to allow for a refinancing from another bank without government assistance.

Since there is no credit model for this scenario, every bank must make an educated guess as to the borrower’s liquidity in Year Five. Banks need to ensure the borrower is strong enough to obtain refinancing AND that refinancing is available. Banks need to guess correctly – how long this pandemic lasts, how behaviors change that could impact the borrower, how fast the borrower resumes pre-COIVD19 cash flow, and how long it takes banks and the capital markets to start lending again. That combination of factors results in a potentially higher POD.

Below, we just use non-covid19 scenarios to model the 15% debt service loan for years two and three and come up with an adverse case, cumulative, five-year probability of default adjustment of 3.70% and then a balloon adjustment with a five-year term of an additional 4.90%. This equates to an approximate 29.09% probability of default.

Keep in mind that the structuring adjustment factors were not for a pandemic case, so if we don’t get a vaccine and don’t get this disease under control, these numbers shoot much higher. Further, we modeled an average retailer. Chances are the demand for MSLP loans are going to come from restaurant, movie, amusement, and similar chains. Thus, we will guess that the average probability of default skews higher so that about one-third of these credits need to be worked out eventually.

Loss Given Default

Calculating a loss given default on a pandemic-impacted credit going concern is anyone’s guess. The average loss given default for bank debt at the start of the year was around 34%, assume current cash flow is down 70% and then ramps up back to normal over the next three years, assume our current state of volatility and you assume about 5x debt leverage to earnings before taxes, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA), you get a stream of cash flows that you can apply a 10% capitalization rate to which equates to about a 53% loss given default.

Performance Risk

Moreover, there is the performance risk of underwriting, servicing, and working out these credits successfully so that banks can escape additional liability from the U.S. Government. While government programs during recessionary times have been fair when it comes to the assignment of liability due to faulty servicing, the risk is not zero.

In addition to the credit and liquidity risk mentioned above, we will add another 0.10% on the total notional amount to compensate for the operational risk of the program. On the good news side, banks do get to keep 0.25% to service and compensate for this operational risk.

Putting This Into Action

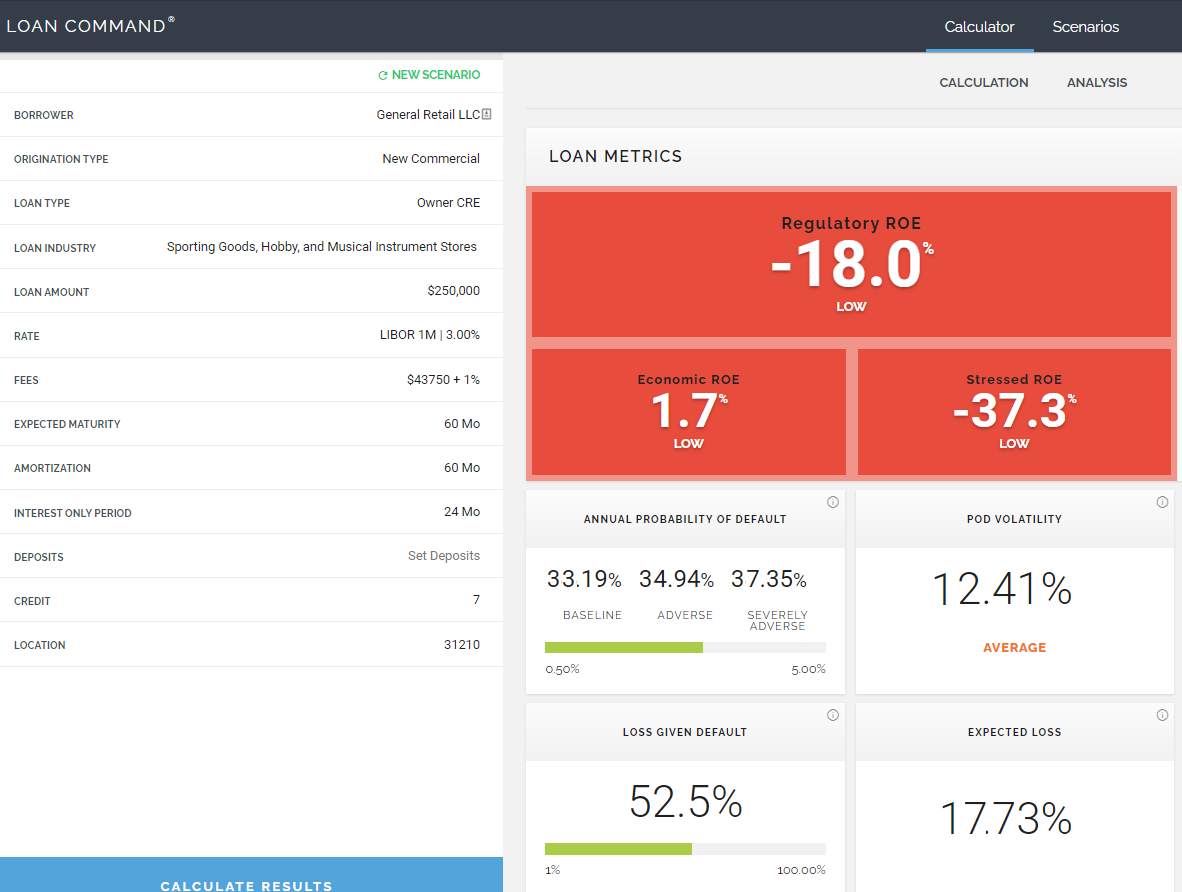

To break this down, if your bank underwrites a $5 million loan through the MSLP program at Libor + 3.00%, it would retain 5%, or $250,000 on its balance sheet. Assume your probability of default skews to the 34% average and a 53% loss given default, that expected loss comes out to about 17.7%. Add to that figure the 10-basis point operational reserve to mitigate the risk of the Program, and the bank is talking about a 19.5% expected loss for these loans.

Now, if this program was structured as a guarantee and the bank would retain the entire $5mm amount, then that would be reasonable. That risk-adjusted profitability would be more in line with a normal loan, and the bank would then have a 0.97% expected loss and could reserve the traditional 1% to mitigate that risk. That structure would also provide an adequate return.

Unfortunately, that is not the case as the bank sells a 95% participation, and with it, the earnings at Libor + 3.00% plus the 1% upfront fee. Thus, for the effort of understanding the program, managing and underwriting, the bank only gets a $250,000, five-year asset, with a 3.8 average life (including the servicing spread) and about a one-in-five chance of going bad. These are not great economics.

In fact, if you go back to our general retailer example, the economics are such, as demonstrated by our Loan Command pricing model below, that a bank will book a risk-adjusted return on equity of about -18%.

The means, of course, that the bank potentially loses money on the most probable scenario. Why would a bank want to do this? It wouldn’t want to take this risk for new customers if it can avoid it. The most likely scenario is that it would take this risk in order to help an existing customer add more capital and increase the likelihood of that customer paying back existing debt.

With the above model, you can back into the exact scenarios where you would do this. The answer, for this particular scenario, is that you would want to make the MSLP loan any time the Bank is expected to lose more than $21,880 on its existing debt to include restructuring, the forgiveness of interest, forbearance, and principal write-offs.

Given the structure and economics, it is no wonder why the MSLP is not getting more activity. It is a difficult program to structure as policymakers have to walk the thin line of helping our troubled borrowers without creating a moral hazard and the catalyst for fraud. This program is close but needs retooling in the form of relaxing some of the borrower requirements and enhancing the economics for banks.

Until that happens, banks need to be laser-focused on how they use this program to make sure they are on the right side of the economics and not unwittingly creating more risks for themselves. Underwriters are placed in a difficult position having to analyze the credit using 2019 data but mostly guessing what the future looks like for a credit and health shock no one has ever experienced in their lifetime. Until this program is retooled, look for both bankers and borrowers to continue to wave at this program like they would the end of a Zoom meeting.