The Single Secret To Building a Profitable Bank

Last week a seven-year-old asked us what banks do. That question got us to pause. How do we explain a whole industry to a seven-year-old in less than a minute, keep his interest, and do justice to the answer? The simplest answer is that banks allow customers to change the timing of their cash flows. It’s really that simple at its core. It got us thinking that some bankers are losing sight of this basic explanation of banking, but top-performing banks use the timing of cash flow to their greatest advantage to increase profitability, enhance customer experience and maximize customer lifetime value. In this article, we explain.

Basic Examples

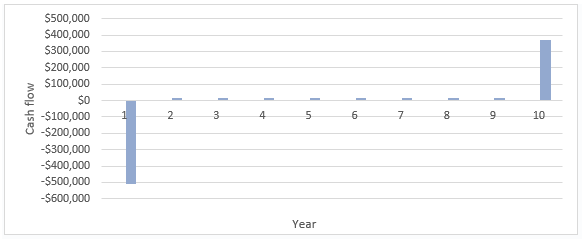

When a customer wants a term loan, they don’t want the bank’s cash; instead, the borrower is aiming to change the timing of their own cash flow. If a borrower wants a $500k loan, they know that they don’t get to keep the $500k, but instead receive those funds in day one, pay interest over the term of the loan, and then pays the balloon for the principal outstanding. The borrower is obtaining $500k today but paying more than $500k during the term of the transaction. A graph showing the cash flow from the bank’s perspective is shown below.

The graph above is not new to any banker, but the nuances of the math will surprise almost all bankers.

Timing is everything – Banking is a long-term game, and banks earn income from customers over many years. In the graph above, we assume that the loan is outstanding for ten years. Over that time period, the economy will experience at least one credit cycle, the borrower’s circumstances will change, credit quality will vacillate, the bank will have an opportunity to cross-sell and upsell the customer, and the lifetime value of the customer is potentially very large. The key take away is that banks must be very discerning about who they want to do business with because the relationship between the bank and client can be very long – the relationship can be painful with the wrong partner.

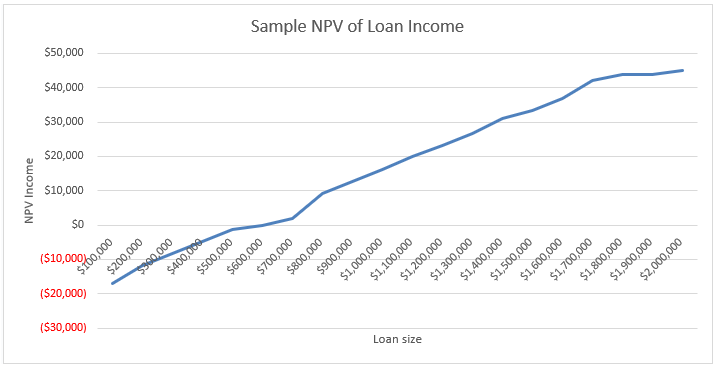

The banking model is highly leveraged but expensive – The graph above shows a $500k loan but a $509,500 cash flow outlay on day one. It costs the bank at least $9.5k to source, underwrite, approve, document, and book this loan to include both direct and indirect costs. The cost to book a loan is highly inelastic, so smaller loans are not as profitable. The graph below shows the net present value (NPV) of income for loans ranging from $100k to $2mm in size. Larger loans are more profitable because it takes almost the same amount of cost to book a loan and to maintain it.

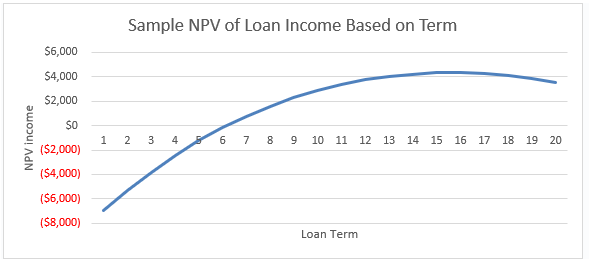

Lifetime value is critical – Everything else equal, the longer the relationship, the more profitable the business becomes for the bank. On day one, the bank has spent substantial resources to book the loan but recognizes only very little income (possibly just the upfront fee, and those are skinny or nonexistent for quality loans). It is over time that the banking relationship becomes profitable. Below is the NPV of income for a loan based on expected life. A $500k loan only becomes profitable after year four or five. Yet most banks structure credits to reprice at year-five – giving the borrower an incentive to shop the relationship. Banking is a marathon, not a sprint – top-performing banks originate strategic relationships for long periods, and a bank’s mantra should be “we are not a bank for every customer, but we keep our customers for life.”

Watch Prepayment Speeds – If banks focus on lifetime value and want longer relationships, they should decrease prepayment speeds and increase switching costs. The expected life of the loan must be part of the pricing decision because the return of cash flow to the bank is so important and the longer banks can maintain earning assets, the higher the net present value of income is to the bank. That means that pricing can be more competitive for longer relationships.

Consider Fee Income – In the current low-interest rate environment, the interest payments on the loan are very small, and banks are challenged to make money on the net interest margin. The industry’s cost of funding has a natural floor of zero, and when interest rates on loans approach that same floor, NIM naturally declines. The single most significant correlation for ROE is non-interest income. The reasons are obvious: fee income is generally an acceleration of cash flow, it remains at the bank even if the customer leaves, and the ability to earn non-interest income in this interest rate environment is critical. That is why top-performing banks create products that allow for fee generation and especially those products that can multiply the present value of the fee and where the borrower does not come out-of-pocket for that fee. The biggest generators of this type of fee are treasury management, consumer mortgages, SBA loans, and commercial loan hedges.

Conclusion

The timing of cash flows is the fundamental concept of banking. To make money in this game, banks need to build a portfolio of net cash flows that generate a return above the cost of capital. It is not about loans, not about deposits, but about the cash flow each customer generates – net of risk, cost, and capital.

Banks need to use technology, service, loans, deposits, and fee products to not only generate profit but lock their customers in for the longest amount of time possible.

The seven-year-old lost interest in our explanation about ten seconds into it. However, if you made it this far, hopefully, you can apply the above nuances, so that your community bank can substantially improve financial performance, enhance customer experience, and maximize customer lifetime value.