How Banks Create Liquidity Risk for Borrowers

In a previous article, we discussed how a loan’s maturity and amortization impacts credit risk and profitability from the bank’s perspective (HERE). In that article, we pointed out that the average commercial loan term at community banks has been decreasing and is now between 3.5 and 4.5 years. Much of the explanation for the decrease in term comes from the misconception that term rates or credit spreads will decrease when the Federal Reserve lowers short-term interest rates (there is no direct relationship between these variables), and borrowers are waiting for term rates to decline to more favorable levels. In that previous article we demonstrated by using loan vintage analysis, amortization schedules, and loan profitability analysis that banks optimize profits and lower credit risk with loan terms between five and 15 years. That analysis was from the bank’s perspective, but in this article, we will look at liquidity risk from the borrower’s perspective.

Creating Liquidity Risk for Borrowers

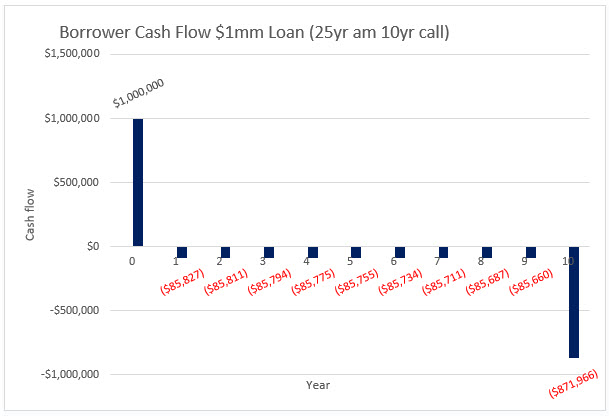

In its simplest definition, banking is the process of changing the timing of cash flows for customers. Top-performing banks use the timing of cash flow to their greatest advantage to increase profitability, decrease risk, enhance customer experience and maximize customer lifetime value. Think of a borrower that needs a loan. The borrower is not keeping the bank’s advances on the loan; instead, the borrower is aiming to change the timing of their own cash flow. If a borrower wants a $1mm loan, she knows that she doesn’t get to keep the $1mm of advances, but instead receives those funds in day one, pays interest over the term of the loan, and then pays the balloon for the principal outstanding at the end of the loan term. The borrower is obtaining $1mm today but paying more than $1mm during the term of the transaction (because of interest due on the loan). A deposit works much the same way, but the funding and repayment is reversed. The graph below shows the cash flow from the borrower’s perspective for a ten-year loan on a 25-year amortization.

There are a few nuances worth discussing for the graph above:

- One of the main effects of changing the timing of cash flows for customers is to create liquidity. The borrower obtains cash (the most liquid asset), deploys that cash for other assets (purchase a business, building, inventory etc.) but at the end of the term of the loan that liquidity is removed – the borrower must pay back the outstanding principal with cash flow from operations or find another financing source.

- The graph above shows that the borrower has ten years of liquidity and during the tenth year pays back $871k. The repayment of principal occurs over ten years and is an annual drain on the borrower’s liquidity. But the borrower has ten years to generate cash, improve its business, and pay down debt.

- Most importantly, liquidity is an item that is most valuable when it is not available in the market. If the borrower’s business is performing well, the value of collateral is increasing, and banks are lending and flush with deposit, liquidity is ample and is not precious. Over 10 years, the economy will undergo one or two business cycles and during a recession liquidity becomes dear and the borrower will have a 10-year commitment term to protect its liquidity position.

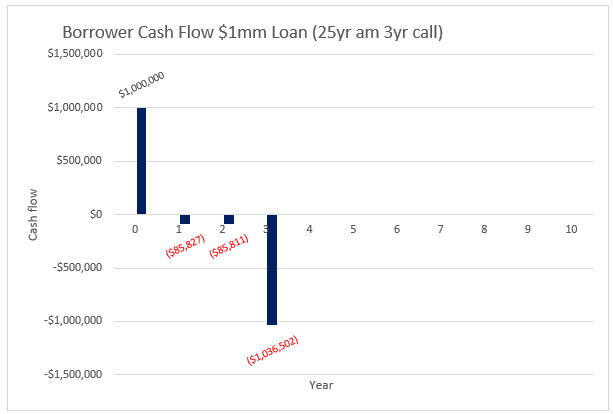

Now let us consider the same loan with a three-year call as shown in the graph below.

This loan structure creates a few issues for the borrower, as follows:

- The borrower’s payment at the end of year three is more than $1mm because of interest for that year. Shorter term loans create more liquidity risk because the final balloon payment is larger than the initial advance.

- It is poor practice for borrowers to let term debt become current. Borrowers lose their negotiating leverage and risk an unfriendly borrower market by letting their debt become current. Term debt should be refinanced at least one year before maturity, making the liquidity risk even higher for borrowers than shown in the graph above. Practically, borrowers should think of this term loan as a two-year source of liquidity.

- In this example, the borrower has less time to pay down debt, less time to increase value of the collateral and less time to generate cash flow from operations. If cash flow from operations decreases (which would most likely decrease the value of the collateral), either because of adverse economic conditions or operating issues, the borrower has to come up with more than $1mm of cash in the final year of the loan. This more than $1mm in the final year of repayment will need to come from available cash flow or refinancing. Again, refinancing will be dependent on market conditions and the borrower business prospects.

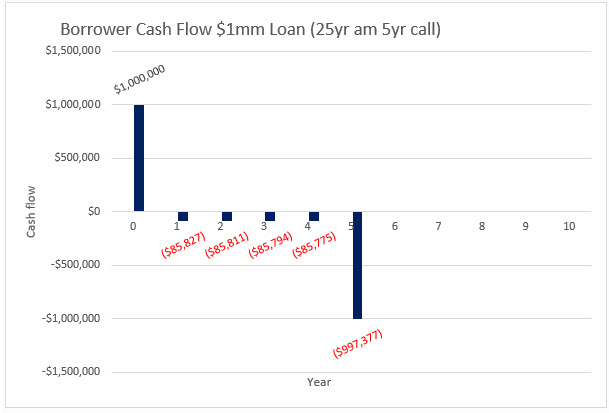

The examples above do not consider the borrower’s friction costs (upfront fees, appraisals, legal costs, etc.) that make the liquidity risk even more punishing for borrowers. Loan cash flows for a five-year call is shown in the graph below for reference purposes.

Conclusion

Longer commitments create a more pronounced change in the timing of cash flows for customers, and thus decrease liquidity risk for borrowers. Retaining liquidity is a crucial factor that borrowers must manage to stay in business. Borrowers that seek shorter term commitments on material debt are inadvertently creating liquidity risk for their business. Lenders that function as trusted advisors to borrowers must be prepared to discuss this risk with their customers and ensure borrowers make sound and reasonable finance decisions to safeguard their liquidity.