How a Loan’s Maturity and Amortization Impact Credit

How does a commercial loan’s maturity and amortization impact credit? Many credit officers would prefer to set shorter maturities for loan repayment terms. The logic is that it is better for the bank to control the credit with a hard stop and revisit credit appetite at shorter intervals. If credit conditions are appropriate, the bank can renew the commitment or re-write the loan, and if credit conditions have deteriorated, the borrower will need to find alternative financing sources. We believe that this logic is deeply flawed and studies on vintage credit and profitability analysis do not support short-term maturities for banks’ credit criteria or return on equity (ROE) goals.

Some Context Around Maturity and Amortization

Currently, we estimate that the average community bank’s commercial loan term is between 3.5 and 4.5 years. But what is the optimal term for maturity and amortization with regard to credit? We use time studies and risk-adjusted-return-on-capital models to help us answer this question.

Let list few misconceptions:

- It is inaccurate to assume that if the bank does not want to renew or re-write the loan that another willing lender will step in. Many banks are stuck with maturing credits in a recession or in cases of credit deterioration.

- Bank credit officers cannot predict future credit downturns. It is true that a shorter term on a loan will lead to less chance of that specific credit being on the books at the bank during the next recession. However, banks need to replenish loan runoff and maturities, therefore, that loan with a shorter term that comes to its maturity date will be considered at the bank for an additional term. Many times, the borrower will want to re-leverage and re-amortize that loan. This puts the bank in a worse position than had the loan been originally booked with a longer maturity. At the time of the renewal, if credit has deteriorated banks face the issue outlined in point 1) above, and if credit has improved, the bank has a longer credit facility with the added burden of cash-out and re-amortization, and potentially lower pricing.

- Most importantly, credit officers are paid to assess credit but not profitability. We will see below that even if longer maturities lead to more credit risk, they may also generate proportionally more revenue, driving up ROE. Many credit officers are simply not attuned to this trade off and make siloed decisions.

What Does Vintage Analysis Tell Us About Maturity and Amortization?

Vintage analysis offers bankers a perspective on the risk and profits of loans based on loan maturity and amortization. Vintage analysis groups loans in a specific period and tracks performance through the life of the loan. The pools can be analyzed for delinquencies, payoff trends, losses (typically charge-offs) and profitability. To effectively use vintage analysis, changes in external factors that do not relate to maturation must be controlled. For example, loans originated in 2006 would show credit stress two to four years later. But that stress would be attributed to the recession that followed rather than the natural maturation of a typical pool. Further, different credit grades within the vintage pool will exhibit different vintage behavior. It is essential to pool loans with similar credit grades.

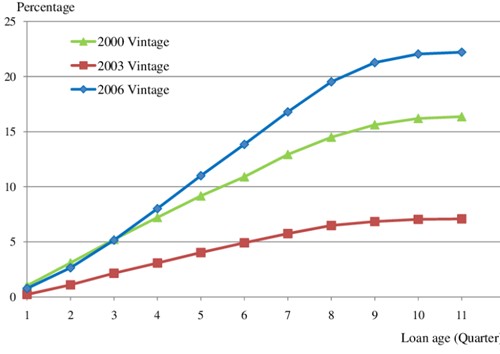

What is clear in vintage analysis of commercial loans is that average per year loss increase in the first few years and then declines. The rise and decline of per year losses depend on the type of loan, amortizing or bullet, and inherent credit strength. However, the average chart of cumulative default rate is shown below on three vintage loan pools. The credit risk (as measured by default or write-offs) starts low, accelerates, and then flattens again. This pattern is consistent across different loans and periods.

The Importance of Amortization

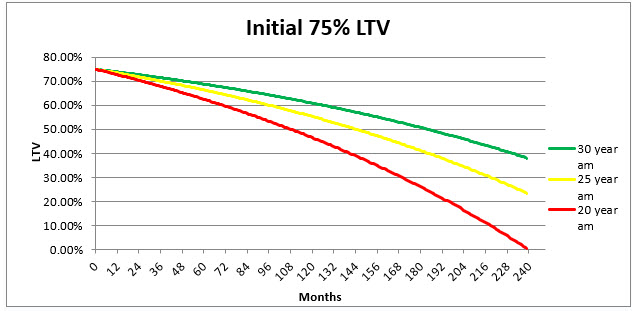

Most commercial loans are structured on a mortgage amortization. Under that formula, little of the loan is amortized initially, and substantial amounts are amortized near the end of the loan. The vast amount of principal reduction never occurs if lenders set balloons before the pivotal point in the loan amortization schedule. Below is a graph showing an initial 75% LTV loan and three different amortization periods (20 years, 25 years, and 30 years). Strictly as an LTV risk to the lender, most of the risk exposure is in the initial term of the loan (1 to 5 years). The graph shows that little amortization occurs until about five years into a loan on either a 20, 25, or 30-year amortization schedule. On a 25-year amortizing loan, only 4% of the loan is amortized over the first 2 years, but 27% of the loan is amortized over the first 10 years.

Profitability

Now the most important analysis for our discussion – tradeoff between credit risk and profit. If a longer term resulted in one extra dollar of expected credit loss, but ten extra dollars in profit, every banker would accept the tradeoff as beneficial. But this analysis is not the bailiwick of the credit officer.

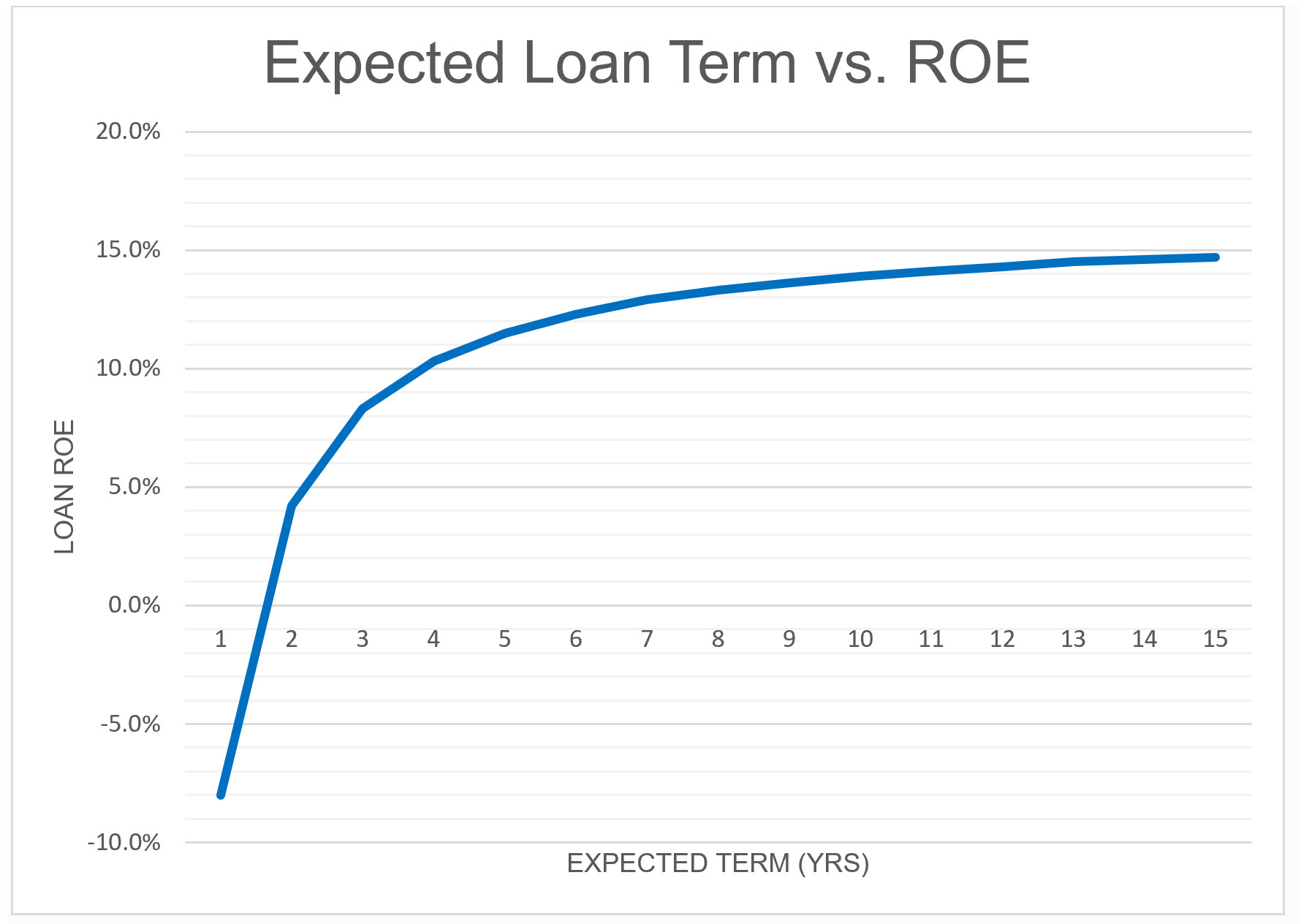

Because it is expensive to source, negotiate and book new commercial loans, long-term loans are typically more profitable for banks (all else being equal – including credit risk). Conversely, short-term loans can be a serious drain on bank earnings. The graph below shows the results from our modeling of commercial loan ROE. Because of the high direct and indirect costs of booking a new credit relationship, loans exhibit a negative ROE (risk-adjusted return on capital, or RAROC) in the first year or two and still subtract shareholder value in year three. Commercial loans become more profitable with maturation, and the ROE levels out after ten years.

Putting This Together

Vintage analysis shows that cumulative credit risk decreases over time (for example, as shown in the graphs below from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis’ FedPerspective) and profitability increases (credit risk held constant). Therefore, the forward forecasted ROE of loans should look much better with longer credits.

A study on vintage level ROI forecasting was conducted with some astonishing results for banks (here). The longer that loans stayed on the books, the higher the ROI (equivalent results would be reported with ROE). The graph below shows this relationship for 20 different vintage pools.

This specific study considered consumer lending, but we can extrapolate comparable results for commercial portfolios.

Conclusions on Optimal Commercial Loan Terms

Every commercial loan must be considered on its specific merits. For example, a single tenant property, with a three-year lease expiration has a strong idiosyncratic credit characteristic. However, the general amortizing, commercial loan has a decreasing risk profile after the initial few years, and a strong uptick in ROE after five years. Bankers want the longest set of cash flows possible at the lowest risk. It is much better on both the credit and profitability side to have one 15-year loan than have to originate three, five-year loans. Due to appreciation, principal paydown and seasoning, that 15-year loan is much more profitable on a risk-adjusted basis than three shorter loans of the same loan amount.

For many credits of an average-sized community bank, ROE is highest for loans with terms from five years or longer. Banks that try to make shorter loans against the customer’s wishes, largely due themselves a disservice when it comes to loan profitability and risk. It is worth taking a look at how loan maturity and amortization effect credit and profitability at your bank to better understand if you are making less than optimal credit decisions.