Should You Waive Your Prepay Provisions With A Refi?

Over the last few years we have published various articles on the pros and cons of commercial loan prepayment provisions, how those prepay provisions impact marketing and sales, loan prepayment speeds, and the relationship between prepayment provisions and customer return on equity (ROE) (some of the recent articles are here, here, and here). We are seeing more community banks incorporating prepayment provisions in commercial loans (especially for fixed-rate pricing). Most community banks are utilizing a declining balance prepayment provision – which if properly enforced, can create value for the bank. Unfortunately, many community banks that include the declining balance prepayment provision dilute the value of this provision by forgoing the prepayment if the loan is refinanced within the bank, the property/business is sold, or the loan is paid off through cash flow from operations. This defeats the purpose and value of the provision in protecting the bank from interest rate risk.

Why Prepayment Protection Matters

Loan prepayment provisions lower prepayment speeds (especially in a stable or declining interest rate environment) and drive higher return on assets (ROA) for banks. There are four main reasons why prepayment provisions increase profitability for banks. The four reasons are as follows:

- Decrease the value of the option held by the borrower to repay the credit when interest rates or credit spreads are lower. Borrowers will retain credit facilities when interest rates rise but are motivated to refinance when interest rates fall – to the detriment of the bank.

- Increase the lifetime value of the relationship. A longer loan pays more revenue over time to absorb the cost of customer acquisition, and as loans season, the credit risk decreases through principal reduction.

- Increase cross-sell and upsell opportunities. Deposit, treasury management, and other product cross-sells require long-term relationships which can benefit from prepayment provisions.

- Reduce negative selection bias in an economic downturn. Strong credits have more refinancing options in an economic downturn, and those are the ones that tend to migrate to competitors during recessions, thereby increasing the concentration of weaker credits at a bank.

Declining Balance Prepay Provisions

Banks use four standard prepay provisions for commercial loans (step-down, lock-out, defeasance, and symmetrical breakeven). The step-down is by far the most common prepayment provision used by community banks, and we are seeing more community banks incorporating that provision in their fixed-rate commercial loans. For example, on a five-year loan, the bank may charge a 5,4,3,2,1 prepayment. The borrower pays the number (expressed as a percentage) times the loan amount corresponding to the year of prepayment. The advantage of this prepayment provision is its simplicity.

We feel that a step-down provision where the starting prepayment percentage equals the term of the fixed rate commitment and declines evenly each year is relatively strong protection for the bank. However, we see that nearly every community bank will waive this prepayment provision if the loan is not refinanced outside the bank (property/business sale, repaid from cash flows, refinanced within the bank). Inadvertently, with these exclusions, the bank is diluting the major benefit of the prepayment provision.

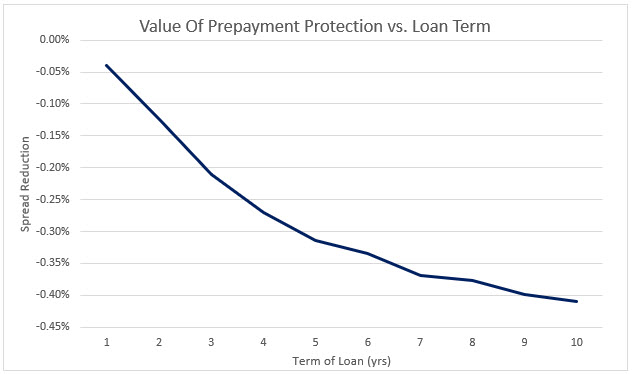

The primary benefit to a bank in obtaining a prepayment provision is the opportunity cost of committing to a credit and giving the borrower the unilateral right to prepay when changes in future interest rates or credit spreads make it more beneficial for a borrower to do so. We can measure this cost using a capital market option pricing tool. This cost to the bank is shown in the graph below.

The graph above shows the economic spread reduction for various loan terms when a meaningful prepayment provision is not present. For a one-year loan, the bank forgoes only 3bps in yield for not including a prepayment provision. However, for a five-year loan, the bank’s economic cost of excluding any prepay provisions is 31bps in yield, and for ten years, that yield reduction is 41 basis points. Including a prepayment provision in a loan increases the economic value of that asset.

All banks that we deal with waive the declining balance prepayment provisions if the borrower refinances within the bank. Those banks will reprice the loan to current market conditions. If rates are lower, the borrower will get the benefit of that lower rate, and this completely negates the benefit of the prepayment provision for interest rate risk protection to the bank. Furthermore, the interest rate risk is borne by the bank if the borrower sells the property/business or pays off the loan with excess liquidity/cash flow – the bank now must replace what is most likely a higher earning asset with a lower earning asset. Over time, and in multiple rate cycles, this behavior results in substantial decrease to a bank’s ROE.

Also, sophisticated borrowers have multiple credit facilities, access to liquidity, and may generate substantial free cash flow. Those sophisticated and liquid borrowers (the credit quality that many banks seek), can payoff above market-priced fixed rate loans with cash on hand, and place new, lower-priced debt, at a near future date. Thereby, negating the prepayment provision in its entirety.

Conclusion

If your bank is using a declining balance prepay provision on fixed-rate commercial loans, any waiver of that provision related to sale, internal refinancing, or prepayment through cash negates the entire interest rate risk that this provision is meant to mitigate. Bankers should question if this provision is worth the sales and negotiating effort, or if another prepayment provision (like the symmetrical breakeven) may be an easier initial sell to the customer, and better long-term protection for the bank.