How A Credit Department May Increase Risk

We estimate that approximately 50% of the community banks in the industry have a credit department that exerts influence or sets standards on loan pricing. While this process appears appropriate and benign, it increases credit risk, decreases bank profitability, and undermines the proper function of bank credit/yield tradeoff. Many bankers feel that since credit officers review all loans underwritten by the bank, a credit officer’s role should also be to opine and compare loan pricing to provide uniformity and support return on capital. However, there are serious flaws with this logic.

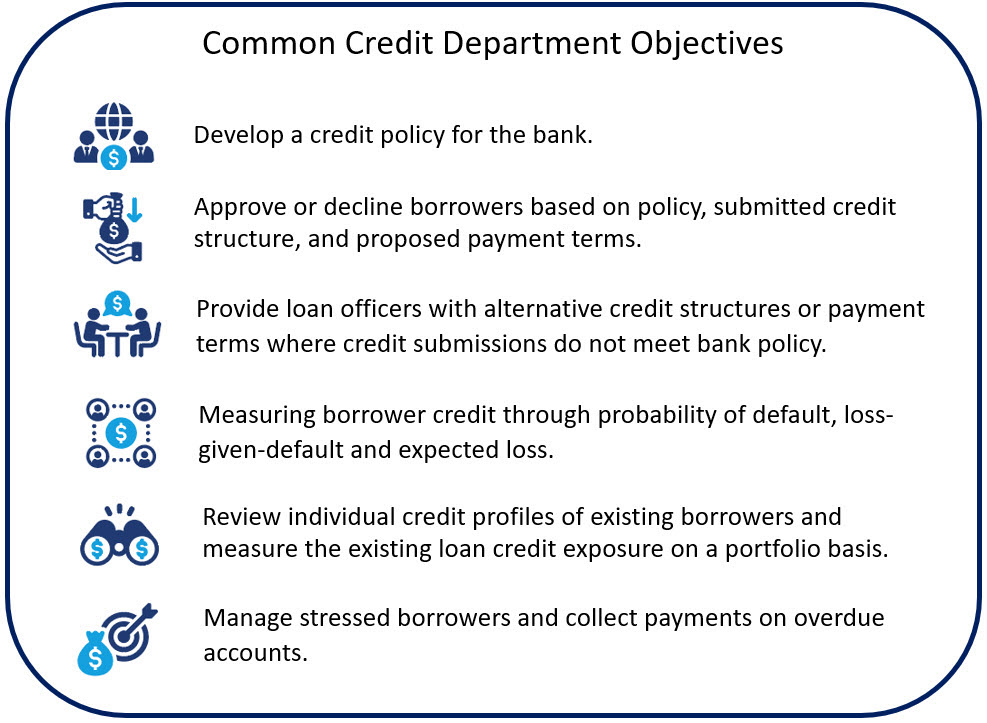

The Role of the Credit Department

A community bank’s credit department serves many functions. Credit officers are responsible for the entire credit process, from formulating credit policy, underwriting, approval, portfolio management, credit review, and collection.

Numerous other functions in the credit department are administrative and ancillary to the broad objectives outlined above. However, one function that should remain outside the credit department is loan pricing.

Objectives of Loan Pricing

Pricing of credit products at banks should be formulated to achieve specific goals. Banks use loan pricing strategies to achieve various goals, but the most common are as follows:

- Increase the granularity of pricing so that capital is priced to maximize ROA for the bank.

- Accurately allocate capital to more profitable business units.

- Maintain market discipline to create uniform pricing decisions at the bank.

- Educate management and lenders to understand the drivers of return on assets (ROA).

- Become more attuned to prevailing market conditions.

- Standardize pricing across divisions, product lines, and relationships.

- Increase profitability as measured by ROA and shareholder value added.

- Manage customer relationships.

- Enhance reporting, control, and governance.

Why A Credit Department Should Not Influence Pricing

When credit officers are given the latitude to recommend or adjust loan pricing, they will rarely recommend lower pricing but naturally gravitate to higher margins – this makes perfect sense since no banker wants to earn lower margins, all else equal, on an already baked deal. The tug of war that invariably develops is loan officers pressure credit officers to accept “lower” loan pricing, and credit officers pressure loan officers to obtain “higher” loan pricing.

By focusing on loan yield, the credit department, inadvertently increases negative selection bias. By emphasizing higher yield over the long term, the credit department decreases the credit quality of the bank’s portfolio. The issue for many banks is this: the performance of all loans should be measured over the life of those credits, but if a banker only sets parameters upfront for a loan (such as minimum yield recommended by credit), the loans that make it into the bank’s portfolio tend to migrate into less credit-worthy buckets. Higher yield comes with tradeoffs – notably, lower credit quality.

Some bankers will argue that the credit department’s chief function is to decline borrowers that do not meet policy and reject substandard credit structure and payment terms. Therefore, credit quality will still be preserved. But this is not the reality. The loan risk spectrum is not “loans that we will do” and “loans that we will not do.” The credit spectrum is very broad, and there are many “loans that we will do,” and the question is at what yield? By allowing your credit officers to recommend or require higher yield, the bank is setting itself up for negative selection bias. Lenders will focus on credit quality the bank will barely accept but are sure to clear the pricing hurdle. Suppose a loan officer cannot get A and B-quality credits approved. In that case, that loan officer will try to get barely bankable credits approved with higher pricing, leading to negative selection bias. The bank’s loan committee no longer gets to see the best credits in the market.

Conclusion

By allowing credit officers input on loan pricing, executive management is unconsciously creating a bank-wide incentive to decrease the credit quality of the bank’s loan portfolio. This is especially dangerous at the end of an expansionary economic cycle when banks should selectively migrate the loan portfolio to improve credit quality. The better way to maximize return and retain desired credit quality is to measure the interplay between the two (risk-adjusted return) and incent the lending line to maximize such returns. Top-performing banks take this a step further and measure and incent their lending team on risk-adjusted return, lifetime value of the relationship, and shareholder value added.