Should Your Bank Consider Investing in a Tech Fund?

Banks investing in tech funds were all the rage in 2021, with hundreds of banks getting involved and investing for their first time. The timing was good for almost all these banks as some of these funds produced triple-digit returns. These technology funds are pitched as a great way to earn an above-average return while gaining exposure to various financial technology companies that can help your bank. In this article, we look at the pros and cons of investing in fintech funds and break down the reasons why you should or should not invest.

The Biggest Reason Why Not to Invest in a Tech Fund

Before you decide to invest in a tech fund, you must overcome one major hurdle – your shareholders. Shareholders have a myriad of investment options, and when they allocate money into a bank, they do so for bank-like returns and risk. No investor wakes up and says they want exposure to financial technology companies and goes looking to make an investment in a bank.

One of bank management’s primary jobs is to allocate capital efficiently on behalf of its shareholders. Having the bank invest in an investment fund is never more tax or control efficient than if its shareholders directly invested in the fund itself (assuming they are accredited investors). That is, because of potentially another layer of taxes and the fact that the shareholder cannot control when they harvest gains and losses, having the bank invest in the fund can be materially less tax efficient. Further, because shareholders cannot communicate directly with the fund, they also lose a vital element of control over the fund.

As such, the first question the board should ask is, does investing in a particular fund compensate for this first layer of risk?

“It’s Not About the Return”

A common refrain in bank boardrooms that you will hear when the bank is about to invest in a tech fund is that the return doesn’t matter, and it’s the gain in education, network, or other non-economic attributes as the primary reason for investment. This refrain has grown louder as equity returns will be harder to come by in 2022 and beyond, given the known reduction of monetary liquidity and the potential for rising rates.

If this is your bank’s position, then the good news is that the analysis is easy – the only question you must answer is – is the gain you get from education and the network worth more than your entire principal amount invested? Note that if your response to this question is – well, we are not planning on losing everything, then you do expect some type of return, and it is incumbent upon your management team and board to have a stated minimum required return (it might be negative), so you can evaluate your team’s performance.

As a starting place, a diversified financial technology ETF (example HERE) is a good place to start to benchmark your target tech fund’s return performance and risk (as measured by volatility). In case it is partially about return, the historical return and risk can serve as a minimum to help with projections and accountability. While the ETF most likely has lower fees helping performance, it is also likely more liquid thereby dampening some of the performance.

“The Tech Fund Will Make Us More Innovative”

Investing in a technology fund to make your bank more innovative, or seem more innovative, is probably the worst reason to make a fund investment. While the statement might be true, the chances are that investing in a technology fund will make you LESS innovative.

For starters, the capital you invest, be it $500k or $10M (the normal range of investment for community banks), is likely to be better deployed to service your customers and/or lower your efficiency ratio. Projects like online commercial account opening, digitized lending, video customer service, and online problem resolution are likely far better investments if your goal is to be “innovative” for the sake of the customer or the shareholder.

No bank has a lack of innovation opportunities, while every bank has an innovation priority problem. Knowing what project to invest in and when to invest is the critical issue, and a fund is likely to exacerbate the problem. When you make an investment in a fund, you only have a vague idea of which companies will receive capital. These companies may or may not be suitable for your bank’s architecture and may or may not be aligned with your bank’s goals.

The managers of the fund get paid in two ways and two ways only – for getting your bank’s capital under management and for producing a return. While they may try to choose companies to invest in with products to meet your bank’s goals, it will be a tertiary goal at best despite what they tell you during the sales call.

Note the very explicit misalignment in goals from the start – Most banks do not invest in the fund for a return, yet funds derive the bulk of their compensation from producing a return. The risk of this misalignment is that the fund could potentially serve as a distraction at best and, at worst, serve to convince your banks of products and services that may not be the best fit for your customer base or technology architecture.

“The Fund Will Help Us Learn”

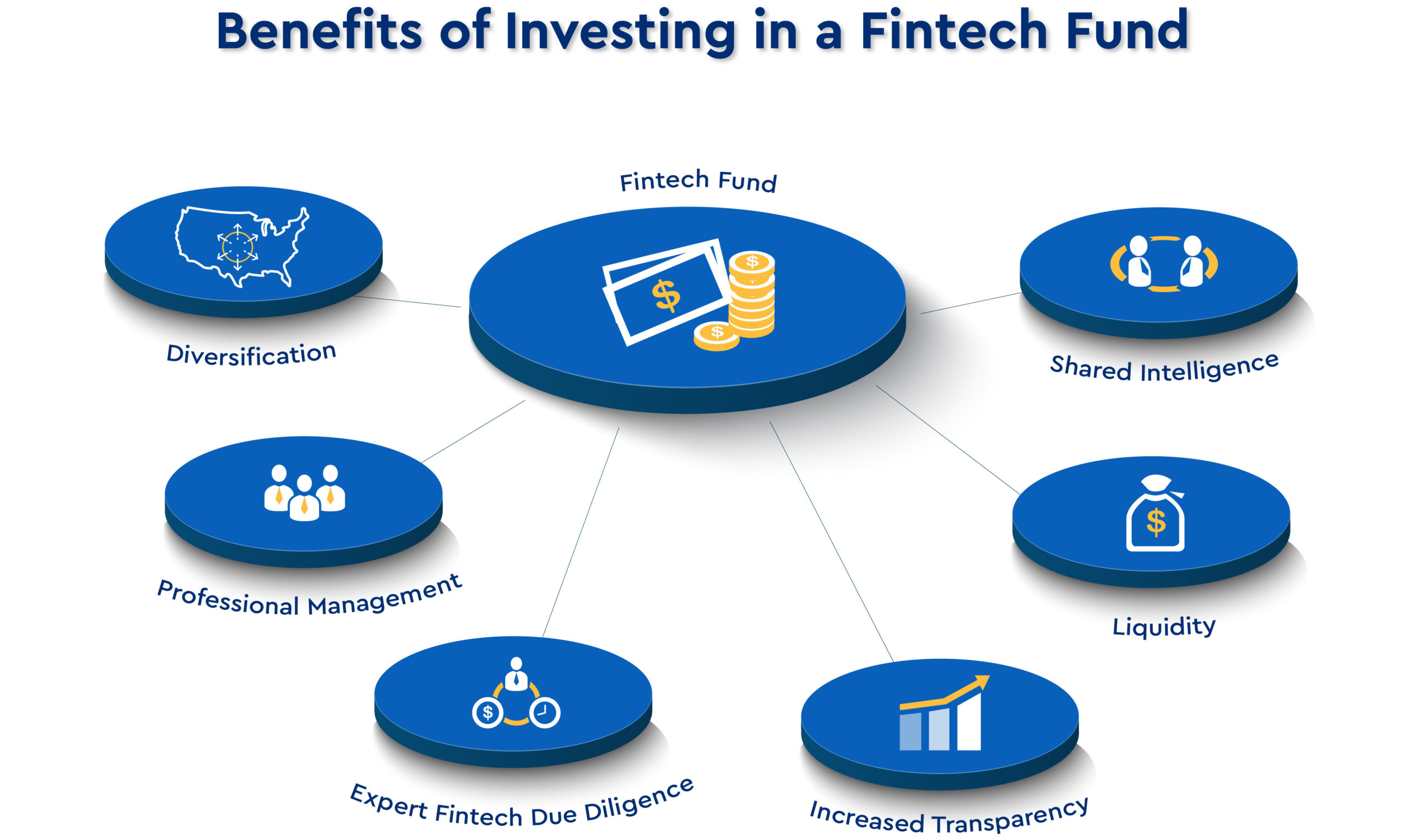

This is likely the best reason to invest, provided the expertise of the fund managers matches the goals of the bank. Funds focused on payments, blockchain, regtech, or identity are worthy areas where most banks don’t have deep expertise, and a fund may give a shared resource that your bank can turn to for strategy and tactics. Generalized tech funds may be appropriate as well so long as the bank makes clear its goals and keeps them in mind when choosing what products to use and promote to its customer base.

The rule of thumb is that a bank should be prepared to use at least two to three of the portfolio companies that are in major needle-moving areas of the bank to have a hope of delivering an intangible return above the economic return in order to make up for the tax and control inefficiencies.

Putting This into Action

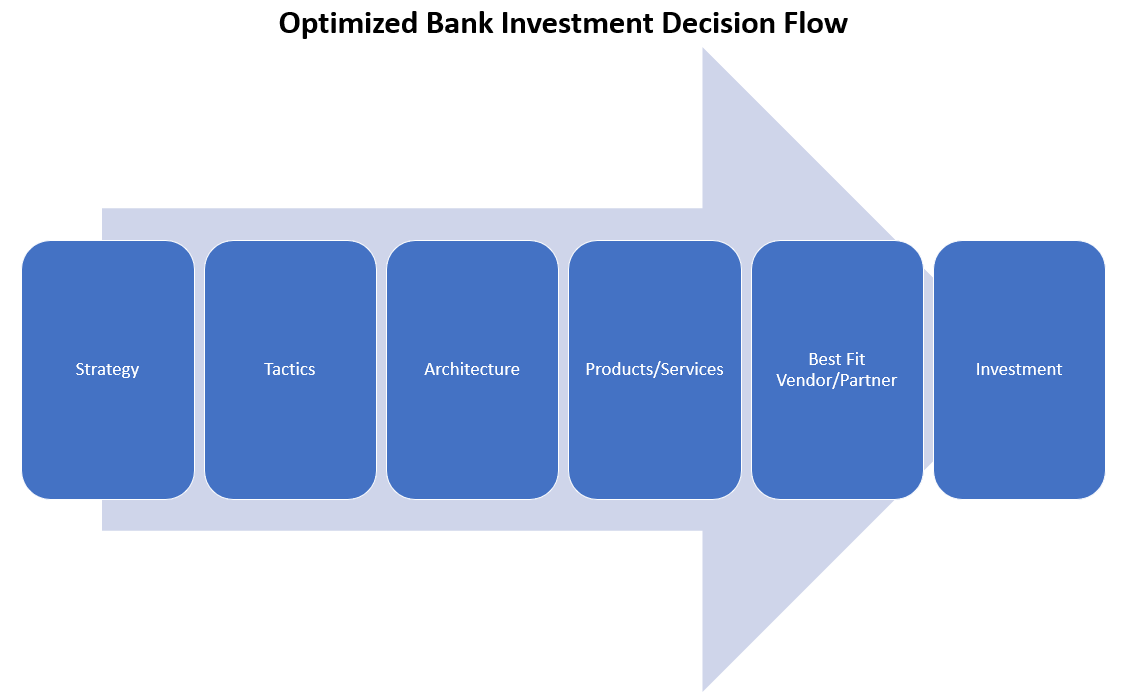

Don’t get us wrong – we are all for banks investing in technology companies. If the companies are strategic to the bank’s efforts and the bank can add enough value to the relationship, then investing equity in the company is a way to capture some of the upsides of value. Direct investments usually ensure that a bank sets its strategy first, then its tactics pick a solution within the upper bounds of its architectural goals, chooses the best-in-class provider that fits the required profile, and then makes the investment.

If a tech fund can fit, at least partially into this paradigm, then it is probably worthy of evaluation. If not, banks should be cautious of proceeding as it will result in the exact opposite of an optimized state. The fund will choose its investment companies and then try to convince the bank that its product/architecture/tactics and strategy fit the bank. The misalignment creates friction between the bank and the fund and within the bank itself by creating confusion and suboptimal performance that hurts morale. The result is the potential for suboptimal use of both human and economic capital, and the problem that all banks have with prioritization gets exacerbated.

If you can find a fund that is aligned with the strategy and tactics of the bank; has expertise both in the targeted domain and with community banking; understands the asset class, and has both the resources and position to source transactions, then your bank is halfway on the path to success.

By combining the above with the articulation of clear goals, a structure of accountability, a dedicated business-focused liaison to the fund (not just the bank’s CFO), and a steady stream of bank-to-fund communication, a bank will have all the makings of a successful process.