The Difference Between Making Versus Keeping Loans

One of the biggest mistakes that some bankers make is believing that banks are in the business of making loans. It is true that banks make loans, but originating a loan is unquestionably an unprofitable business. Banks earn an acceptable return on capital by keeping loans, not by making them. We recently worked with our lender on a refinancing opportunity that we want to showcase to explain our strategy.

Why Making Loans is Unprofitable

Managers often stress the importance of relationship banking. Typically this means that the longer lifetime value of a customer creates more revenue and profit, and the cross-sell and upsell opportunities improve, and a bank can obtain a larger share-of-wallet with longer relationships. However, at a very granular level, originating a loan creates negative ROE for the bank. It is expensive to originate a loan for the following reasons:

- The bank needs to source multiple loan opportunities because the bank will lose some opportunities to competitors and decline some loans through underwriting.

- The lender will use time and effort to court prospects that will never show the bank a loan opportunity.

- Multiple bankers need to underwrite loan opportunities, and management needs to review and approve the credit.

- The bank will also spend scarce resources in the process of title work, documentation, onboarding, and initial due diligence to book a loan.

- Winning a competitive bid for a loan means that the winner often showed the lowest price or loosest credit terms – not a recipe for long-term profits.

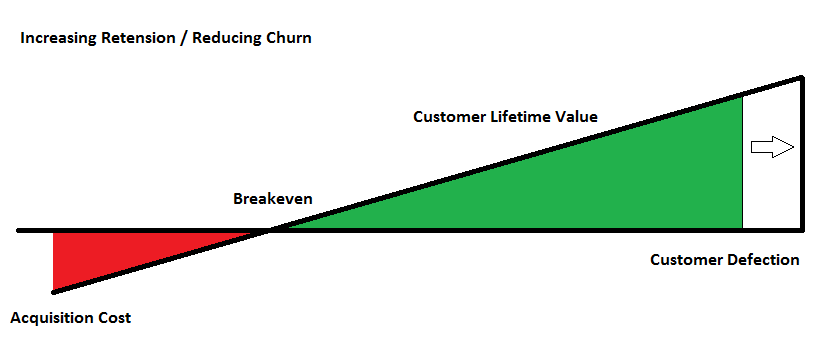

Therefore, a bank’s strategy must be to increase retention and reduce loan churn. Longer loans are just more profitable, and the concept is shown in the graph below.

Borrower Opportunity

We are currently working with a lender at our bank on retaining an existing loan to a physician. The loan is used to finance the business practice and office building of the doctor. The $2.5mm loan was made by the bank in 2017 at 4.5% fixed for a 5-year term. The borrower approached our lender with an offer by a competitor bank for a 10-year fixed-rate loan at 4.25%. Our lender wanted to counter with a cheaper rate on a new 5-year fixed rate.

Here are our observations about making a loan versus keeping a loan.

- There was no prepayment protection on the initial loan because the bank focused on making the loan and not keeping the loan. If a borrower seeks long-term financing, then the loan must have some prepayment provision. We always obtain a prepayment provision, and we do not believe that there is any market where the borrower will not accept one if the loan is properly structured and priced.

- If the loan to finance long-term assets is worth making, it is worth making for the longest term acceptable to the borrower. The 5-year term may have been an acceptable ALM decision in 2017 but created an unacceptable refinance risk for the bank. Banks should prefer the longer term to allow the loan to substantially amortize to decrease credit risk. The amortization on mortgage-style loans is small in the first 5 years and accelerates substantially after 5 years on 20, 25, and 30-year amortizations. The initial 5-year term was not optimal for either the borrower or the bank.

- If a banker is in the business of keeping loans, the banker will not let the borrower retain the loan within one year of maturity. The banker would be approaching this borrower to offer various options to refinance with the bank given the low level of current interest rates. Waiting for the borrower to obtain a competing offer invites lower spreads or a looser credit structure. Keeping loans involves active marketing to existing customers to help prevent poaching.

- If offering a 5-year term was a mistake in 2017, it is even a worse mistake in 2021. To win the loan from a competitor offering a 10-year fixed, the lender would need to sacrifice substantial margin or credit structure on a new 5-year term today. Again, if the loan is worth making it is worth making for the longest term acceptable to the borrower – in this case, the borrower would accept 10 to 20 years. The lender could take the young doctor off the banking market for the remainder of the physician’s career by matching the loan term to the doctor’s expected career span.

- But the point above has a serious structuring flaw. Commercial loans are subject to amendments, collateral substitutions, cash-outs, and assumptions. Why would a banker propose a 20-year commitment knowing the possible changes in the loan’s life? By structuring the loan to be as flexible as the borrower needs. We structured the loan to be assumable, assignable, and expandable to fit the borrower’s needs. This creates value for the borrower, allowing the bank to price with additional credit spread and keep more loans.

Conclusion

There is a vast difference between the strategy of making loans and keeping loans. The latter is the underpinning of relationship banking and creates value for both the borrower and the lender. Many loans are structured to be made over and over again, thereby decreasing ROE for banks because some banks incent and teach lenders to make loans rather than to keep loans.