In our last blog, we reviewed ZIRP (zero interest rate policy) strategies deployed by various central banks. We discussed how ZIRP strategies had been deemed by many economists to be ineffective over the long-term to stimulate economic growth and stoke inflation. We considered forecasts by economists, the forward interest rate market, and FOMC policy member’s future rate path expectations – all point to a low probability of decreasing interest rates. However, one loud voice has been a champion of lowering rates to zero or even negative – the President of the United States.

Despite the market not predicting substantial lower interest rates over the next ten years, many banks are considering how to protect their commercial loans should interest rates decline materially, or head below zero. In this blog, we will outline some ways that community banks should assess the need for floors in commercial loans, and we will recommend some floor valuation strategies and loan structuring strategies to protect banks in the unlikely event that interest rates decline materially.

Why Floors May Make Sense

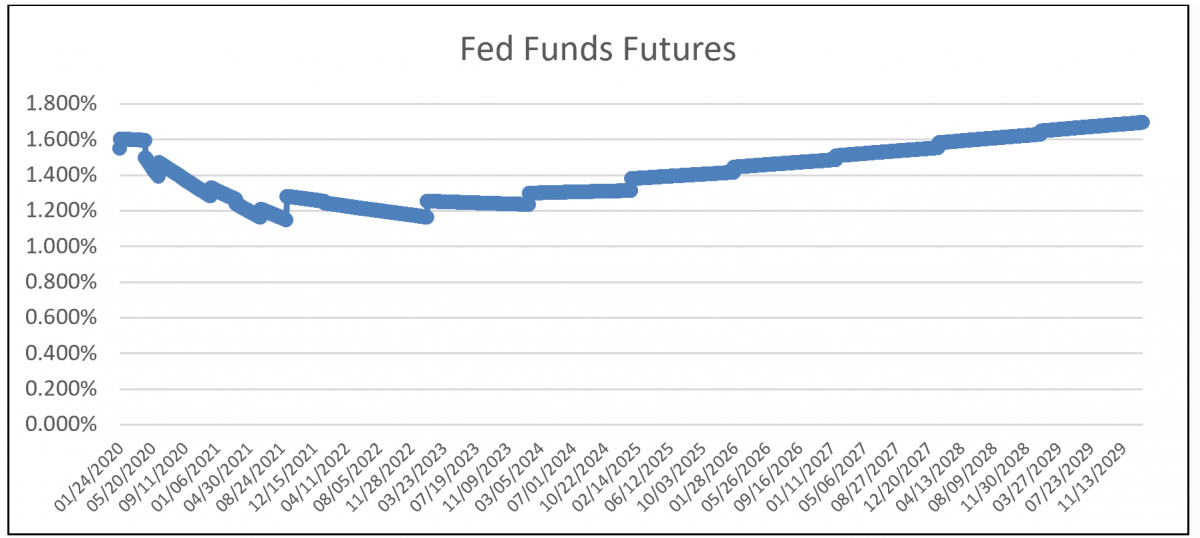

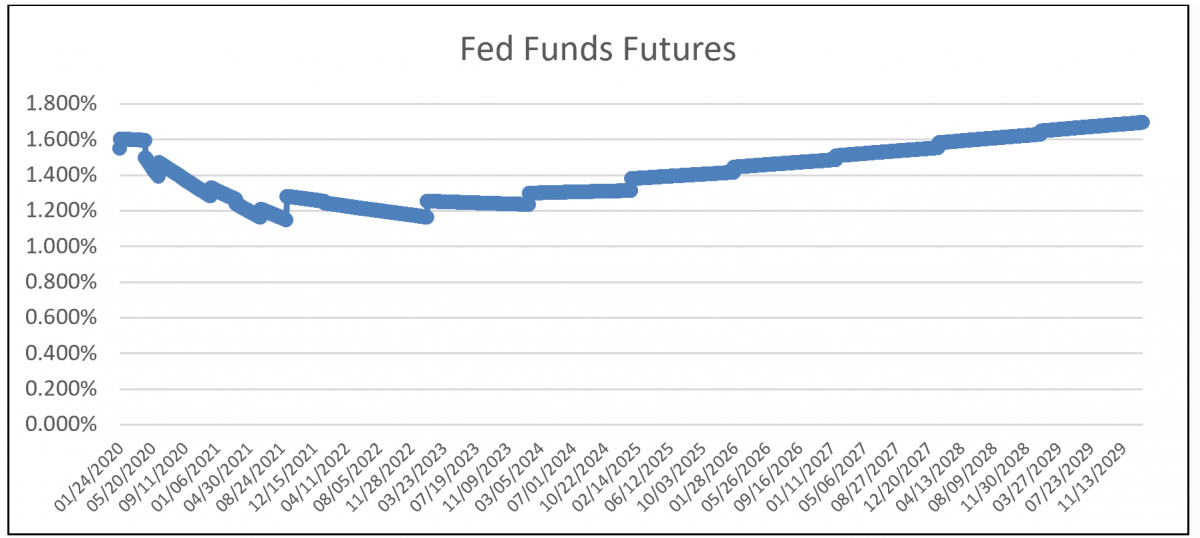

While the market does not expect short or long-term interest rates to head to zero (as shown in the Fed Funds futures graph below), it does not mean that the market ascribes a nil percent chance that interest rates do not go to zero.

The market prices the probability of interest rate movement based on volatility as measured by the standard deviation. Currently, the 1-year Fed Fund is approximately 1.42%. One standard deviation for this one-year rate is about 22bps. Therefore, there is a 68% chance that during the year, Fed Funds may be as high as 1.64% or as low as 1.20%. We can then develop probabilities that Fed Funds fall to 0.98% (two standard deviations move lower) or 0.76% (three standard deviations move lower), etc. The market currently ascribes a minimal chance of ZIRP (and next to a nil chance of interest rates heading to zero over the next ten years).

However, even if the chances are small, the impact on banks may be significant. So should banks be protecting their commercial asset yield with floors?

General Value of Floors

Finance theory teaches us that three input variables govern the value of the floor – but this is wrong. There are four input variables that dictate the price of floors and the fourth variable is the difference between textbook knowledge and practical application.

The four variables dictating the value of the floor are as follows:

Term of the floor – the longer the term, the more valuable the floor because of the higher possibility of payout in the future and more payout periods. The market for floors is quite liquid up to five years and somewhat liquid to ten years. All else equal, the longer the floor the more value the floor provides.

Strike level – the lower the floor rate, the cheaper the floor. The relationship is not linear, however, since well out of the money floors (even floors strike levels that are five standard deviations from expectation) are dear to brokers who may be asked to pay large sums on rare occasions.

Volatility – more volatility increases the value of floors. Another way of stating this is that the payout on the floor becomes more likely as each standard deviation becomes wider.

Size of the floor – floor value is measured in basis points. For example, if the cost of the floor is 1%, the buyer would pay $10k for a $1mm floor, and $20k for a $2mm floor. But this is a textbook notion. In reality, there are substantial friction and transaction costs to buying floors in the market and the cost of the floor (stated as a percentage) increases sharply when the protection amount is small. Therefore, while a $100mm floor may cost 1%, the exact same floor for $1mm may cost 2%.

Contractual vs. Prepayable Floors

Another important concept for community bankers to remember is the distinction between a capital market floor and an embedded floor in a commercial loan. In a capital markets floor, the purchaser of the floor pays the seller a fee, and a termination of the floor by the purchaser requires the seller to return the remaining value of the terminated floor. Therefore, the floor purchaser will always recognize the value of the floor regardless of whether the floor is held to maturity or not.

An embedded floor in a commercial loan is a different animal. Adjustable and floating-rate loans are almost always either prepayable at the borrower’s option without penalty or have a short commitment term. We have yet to see adjustable credit facilities with term beyond one year, where the borrower owes a prepayment penalty to prepay the loan. Banks that embed a floor in loans without prepayment penalties get almost no benefit from those floors. Certain bankers make the argument that while some borrowers may prepay loans when interest rates fall below the embedded loan floor, other borrowers will stay in the loan. But evidence continues to show that borrowers that have no options to refinance their loan will stay with the floor, while borrowers that are desirable because of credit, relationship, or profitability measures will be poached by other lenders and will prepay their floored loan when interest rates fall. Ultimately, the embedded floor without a prepayment provision is a negatively selecting asset for a lender – good quality borrowers either prepay their loan or force the elimination of the floor through an amendment, while poor quality borrowers stay with the bank. Therefore, suboptimal results are achieved by the bank either way.

Strategies Deployed By Banks

We have seen five strategies deployed by banks when utilizing floors for commercial assets that may work well for community banks.

Capital market floor per loan – a few banks, but not many, have purchased capital market floors on a loan-by-loan basis. This makes sense, especially if the borrower chooses to hedge the loan; the loan is large enough to obtain good execution (generally over $2mm, and preferably over $5mm); the term of the loan is ten years or shorter. For example, for a $5mm, 25 due ten loan, the cost of a floor at zero strike level is about 1% of the loan amount, the cost of the floor at 0.50% strike level is about 1.5% of the loan amount and the cost of the floor at 1.0% strike level is strike is about 2.25%. Given the shape of the yield curve (flat and low), a zero-cost collar (buying a floor and selling a cap) does not price attractively to a borrower. This solution may work with some loans, but it is an expensive solution for the borrower, who ultimately pays the price of the floor through a higher loan rate.

The mix of commercial loans – by far, the most prevalent strategy at community banks is to target a mix of commercial loans to achieve the desired ALM position. Banks generate some fixed-rate loans (helping protecting NIM if interest rates decrease) and some hedged loans and floating rate loans (acting to expand NIM if interest rates rise). This is the simplest and least costly solution that also fits well with current borrower demand in the market.

Hybrid rates – a few banks are structuring loans with different payment streams over the life of the credit facility. For example, some banks have introduced fixed then adjustable-rate commercial loans. During the initial period, when the bank is concerned about falling rates, the loan yield is fixed. The tail end of the loan is floating, which the borrower may fix through the purchase of a hedge. This solution is easy to deliver but only provides protection to the bank from falling rates during the initial fixed-rate period.

Premium pricing – rather than embed a floor that may be prepaid by the borrower without consequences, some banks charge more for the floating rate spread instead. Consider that a floor increases the cost of the loan, and the cost is always borne by the borrower regardless of who writes the check or makes the payment. Instead of paying a 1% premium to a broker to obtain a zero strike floor, the bank can increase the loan spread by 20bps (the equivalent of the one-time cost of the floor premium of 1%). Instead of paying a dealer the 1% premium to obtain a zero strike floor, the bank now has the equivalent of a 0.2% floor through the higher spread. Economically, the bank is ahead by not having to incur transaction costs.

Balance sheet hedging – most of the regional and national banks have migrated to this solution. These banks originate primarily floating-rate loans and let borrowers enter into hedges to fix the loan rate. The banks then purchase large notional floors to protect their portfolio of commercial loans. The advantage is that larger floors are comparatively cheaper to purchase, and the floors can be layered at advantages periods (when interest rates increase, making the floors cheaper to purchase).

Expectation versus Risk

While the probability of interest rates heading to zero is low, that probability is not nil. Therefore, community banks should be paying attention to their balance sheet and stress testing, both increasing and decreasing interest rates. Ultimately, any ALM solution must allow commercial lenders to properly address current commercial borrower demand – with the yield curve flat and low, most borrowers with long-term financing needs are seeking fixed-rate loans, with the longest terms and the lowest rates.

Tags:

Published: 02/20/20 by Chris Nichols