Which Prepayment Structure Do You Use?

In recent articles (HERE) we discussed the importance of commercial loan prepayment speeds. We explained why loan prepayment speed is a major factor influencing a bank’s profitability, and how national banks use historical analysis, quantitative modeling, and predictive analytics to structure loans to increase loan retention (decrease loan prepayments). We also outlined how various input factors affect expected life of a loan. These factors include contractual term, business cycle, yield curve, loan size, loan type, DSC, LTV, rate structure (fixed vs. floating), and prepayment penalties. The key factor affecting a loan’s expected life, after contractual term of the loan, is the specific loan prepayment provision. The strongest prepayment provisions (e.g., yield maintenance, lockout, or declining balance for full loan term) have the most influence on expected loan life. In this article, we will discuss which prepayment structure community banks should consider and apply to their loans to obtain borrower acceptance and improve the bank’s financial performance.

Importance of Prepayment Provision

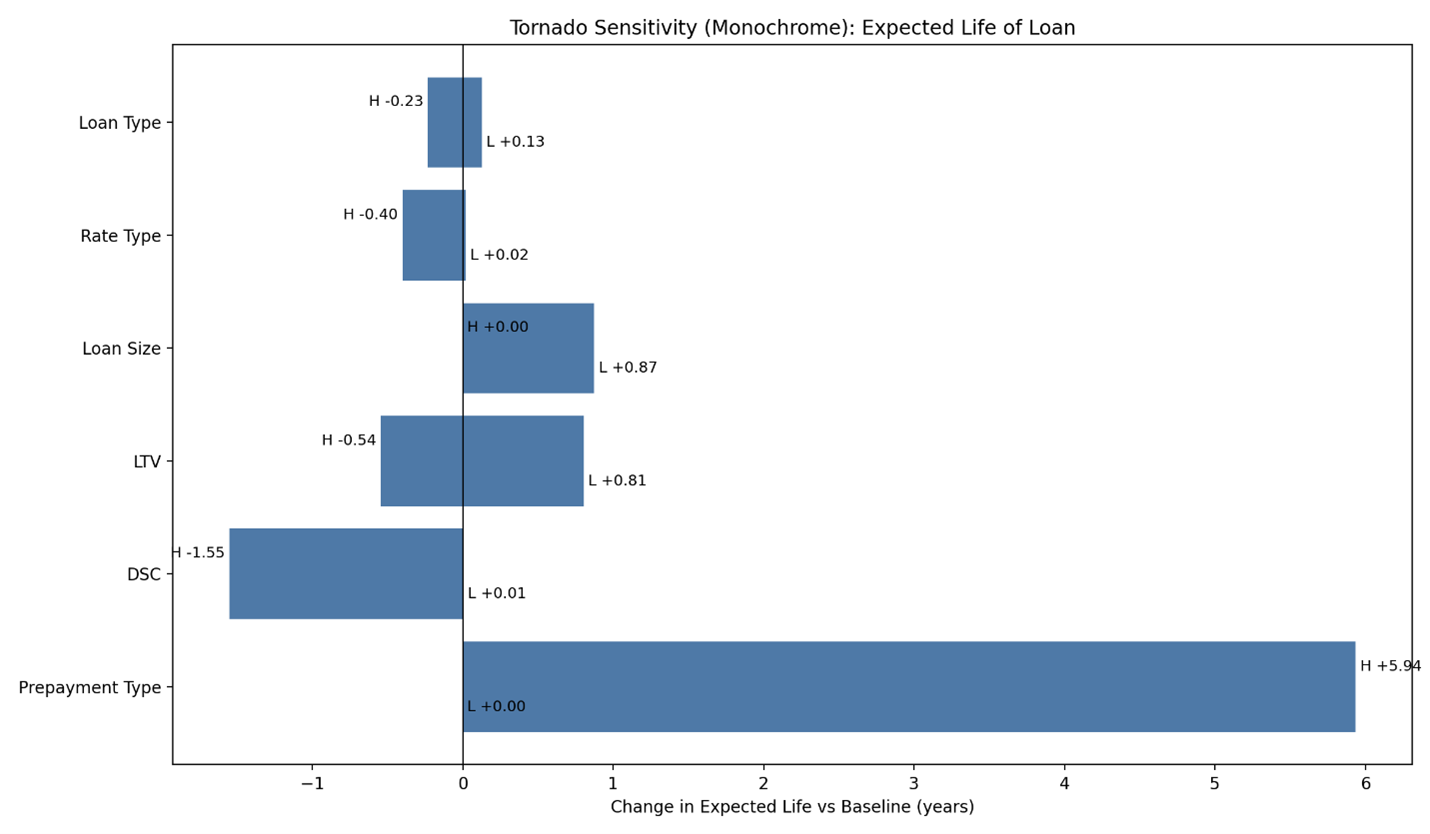

The type of prepayment provision (or lack thereof) may increase the annual prepayment speed by over 10% per annum. The graph below shows the sensitivity analysis for the input variables of a standard prepayment model. It shows that the prepayment provision (bottom bar) is the most effective in increasing expected loan life.

The specific prepayment provision can extend the life of a 10-year contractual term loan by almost six years. For example, a 10-year fixed-rate loan with a lockout has an expected life of almost 10 years, but only 3 years if that same loan has no prepayment provision.

Types of Prepayment Structure and Provisions

Step-down

By far the most common prepayment structure used by community banks is a step-down prepayment penalty. For example, on a five-year loan, the bank may charge 5% of the notional amount the first year, 4% the second and so on. This is called a “5,4,3,2,1” structure. Also common for a five year loan is a 3-2-1, or 2-1-1 prepayment structure. The borrower pays the number (expressed as a percentage) times the loan amount corresponding to the year of prepayment. The only advantage of this prepayment provision is its simplicity. The disadvantages are substantial.

First, because it is hard for a banker to explain why the bank needs the provision for economic reasons, the provision is typically difficult to sell to a borrower. Thus, it is diluted (what starts as a 5-4-3-2-1 initial proposal is pushed back to a 3-2-1 or 2-1). Second, enforcing becomes a reputational risk for the bank. While contractually binding, the borrower will complain about paying it, and banks often succumb to waiving it. Third, it is disengaged from any market, credit or interest rate movement. Fourth, the provision usually allows exclusions such as prepayments resulting from excess cash flow from operations or internal refinancing – which defeats the whole purpose of prepayment provisions.

Lock-Out

A lock-out prohibits any prepayment during a specified period. This provision is rare, but we see it utilized in municipal financing and, in some rare instances, insurance or conduit deals, but it is rarely accepted by commercial borrowers. Most commercial banks choose not to use such provisions in their loan agreements.

Defeasance

This provision is used extensively by insurance companies and conduits. It is extremely disadvantageous to borrowers. The provision is rarely properly explained to borrowers, and we have never seen a borrower presented with a termination scenario before the loan is executed – because the borrower would never signup for the provision if they understood the cost.

Symmetrical Breakeven

This provision is used for hedged loans and results in prepayment speeds as low as lock-out provisions. This provision trues up or creates a neutral cost/benefit for prepayment based on interest rate movements. The borrower becomes indifferent, from interest rate movement perspective to prepayment, whether rates are higher or lower. The provision aligns the borrower’s view in that if the borrower expects rates to rise in the future, the borrower collects a fee upon prepayment but must pay a fee upon prepayment if rates are lower. The provision is easier to sell because it creates symmetrical prepayment (both positive and negative consequences). The provision is standard for national and bigger regional banks that offer competitive long-term fixed rate financing. The reason that borrowers sign up for the provision is that they accept the fact that the bank has a true cost of loan prepayment if rates are lower, and likewise, the bank has a true benefit of a loan prepayment if rates are higher and the benefit is transferred to the borrower.

But the main reason we like this prepayment provision is the flexibility it offers the borrower and lender for future financing. The provision can make the loan assumable and collateral substitutable. That is an immensely powerful feature which can also incorporate prepayment windows, partial prepayment windows or prepayment windows based on preset fee amounts.

Four Reasons for Prepayment Provisions

Prepayment provisions increase loan life, and this drives profitability for banks in four specific ways, as follows:

- Decrease the value of the option held by the borrower to prepay the credit.

- Increase the lifetime value of the relationship.

- Increase cross-sell and upsell opportunities.

- Reduce negative selection bias in an economic downturn.

Unfortunately, the competitive reality is that lenders and borrowers will heavily negotiate terms, conditions, and pricing for every competitive loan situation. Prepayment provisions are quite easy for borrowers to negotiate away for two reasons – first, other competitors are willing to concede them, and second, the provision is not internally compelling to the borrower. For a lender to successfully negotiate a prepayment provision (or any loan provision for that matter), the lender must convince the borrower that the competition will also insist on a similar provision or (but preferably “and”) that the provision is in the borrower’s interest. This reasoning eliminates the usefulness of most prepayment provisions on most loans, except for symmetrical breakeven on hedged loans. Stated another way, most prepayment provisions are not accepted by borrowers and not heavily marketed by banks, except for symmetrical breakeven provisions for hedged loans.

Conclusion and Applicability

Community banks can increase loan profitability using smart prepayment provisions, without having to pass any costs or additional fees to commercial borrowers. Practically we see community banks use the symmetrical breakeven prepayment on hedged loans which creates a neutral cost/benefit for a prepayment based on interest rate movements. The provision better aligns with both the lender’s and the borrower’s interest rate sensitivity, and it is a standard provision at most national and larger regional banks that offer long-term fixed-rate financing. In a future article we will compare real world prepayment speeds and ROA/ROE for loans subject to the symmetrical breakeven prepayment provision compared to similar commercial loans without such prepayment provisions.