Last Friday’s economic data indicated that U.S. nonfarm payrolls rose by 2.5 million in May, compared with expectations for a decline of 7.5 million. In April, nonfarm payroll fell by 20.7 million in the largest single-month drop in records dating back to 1939. Throughout last week, interest rates rose (the ten-year yield rising by 25bps) and the yield curve steepened relentlessly – spread between five-year notes and 30-year bonds widened on Friday to 120 basis points, a level last seen in December 2016. Is this potentially a paradigm shift, and has anything changed for community banks and how they view their business model and interest rates in the near future?

History Tells Us

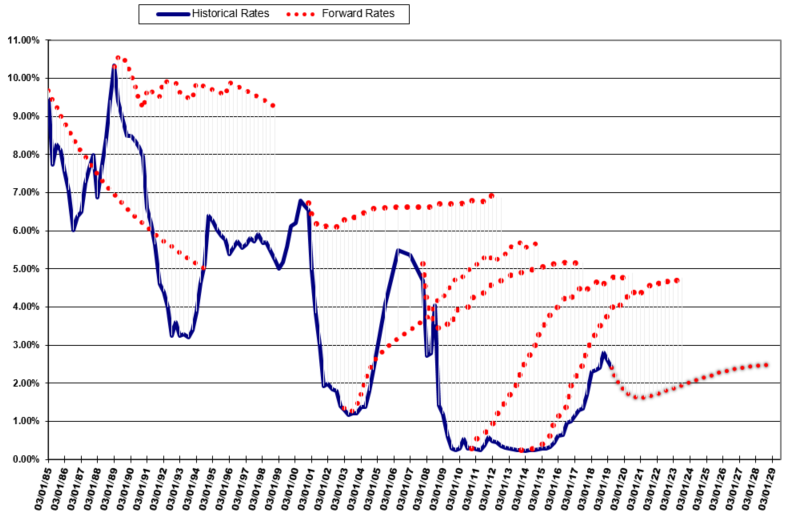

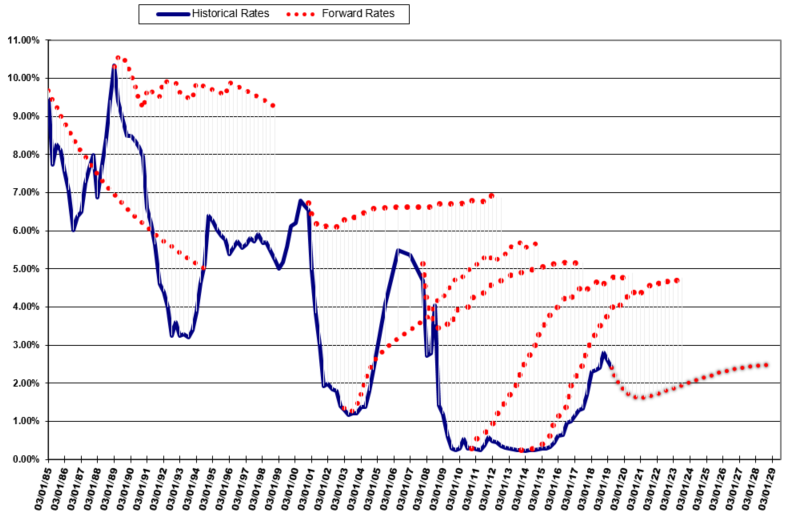

Yes, this was a surprising report, but it is just one job report, and there will be many twists and turns in the reopening of the U.S. economy. No market participant, include Jerome Powell and the Federal Reserve, can predict future interest rates. Below is a graph showing in the blue line the actual historical short term rates (and proxy for banks’ COF) and the dotted red line representing the market’s expectation of future rates at various points in history. Clearly, the market is a poor predictor of future interest rates.

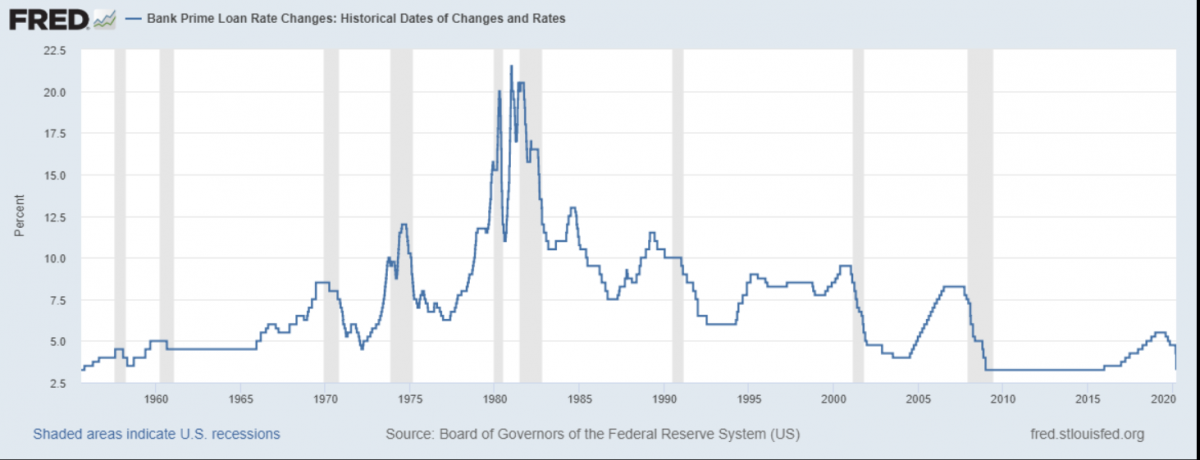

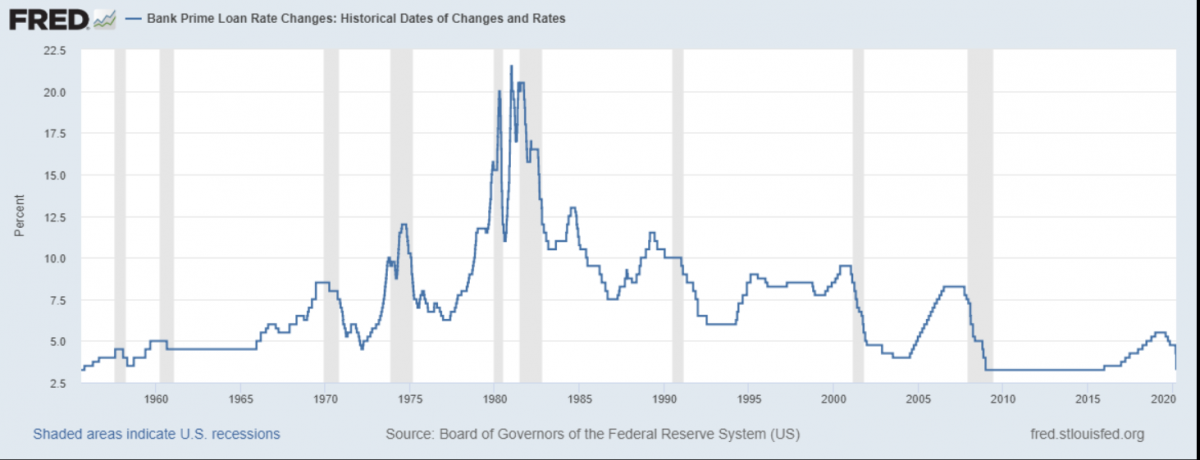

Many market participants and investors have been sleepwalking the last three months claiming that short term interest rates will not move again in our lifetime. In fact, many traders are on the record claiming that the Fed will have little motivation to raise interest rates anytime between now and 2025. But interest rates demonstrate both cyclical and secular movements. Below is a graph showing the Prime rate from 1955 to the present. The graph shows that interest rates demonstrate peaks and troughs shaped by business cycles, but there are also long-term secular movements that are shaped by other forces that occur over many decades.

We do not know where we are in this cycle and if any secular changes are in the work. What is not arguable is that ten-year Treasury yields at less than 1% are historically unprecedented and still signal a highly pessimistic view of the U.S economy, but that sentiment can change quickly. Room for interest rates to rise is much extensive then room for interest rates to fall.

Implications for Banks

If future interest rates are typically unpredictable because we cannot assess the future path of the business cycle, then today, the future is even more mysterious. Through the ups and downs of business cycles, banks succeed best by avoiding a risk-for-yield business model and instead construct an advisory business where taking risks may be just one element in delivering a customer-centric solution.

If there was a time to extend asset duration for banks for yield premium, it would NOT be now. Instead, banks should be securing the most creditworthy customers, offering sticky products that make switching unappealing, and keeping the loan portfolio duration as short as possible.

Tags:

Published: 06/08/20 by Chris Nichols