What Are You Going To Do With Your Savings Accounts?

More than a year ago, the Federal Reserve changed Regulation D, Section 19 to allow an unlimited amount of withdrawals or transfers from a customer’s savings or money market account. Most banks immediately changed their policies to pass on this freedom to their customers. Some banks proactively left the limit in place or modified the limit. Still, other banks ignored the whole change. No matter what your bank did, there is likely an existential crisis lurking below the surface, and it revolves around what the future holds for your savings and money market accounts.

Background of Regulation D

Regulation D (Reg D) was a mess from the very start. Enacted during the Great Depression to manage the reserves banks kept with the Federal Reserve, part of the regulation limited withdrawals or transfers from a savings or money market account. To stabilize deposits industry-wide, customers were limited to no more than six transactions that fall into specific categories (checks, debit, electronic transfers, etc.) per statement period for savings and money market accounts. The six-transaction limit applied to transactions between accounts at the same bank, while Reg D limited these transactions to outside institutions to three per statement period. Customers were free to go in person to the bank or use an ATM to move money; it just couldn’t be “convenient.”

Many banks and customers used an array of loopholes to get around Reg D from the very start. On the other side of the coin, some banks enforced the letter of the law and saw it as a money-making opportunity. Banks would often charge customers $5 or $10 for exceeding the limit.

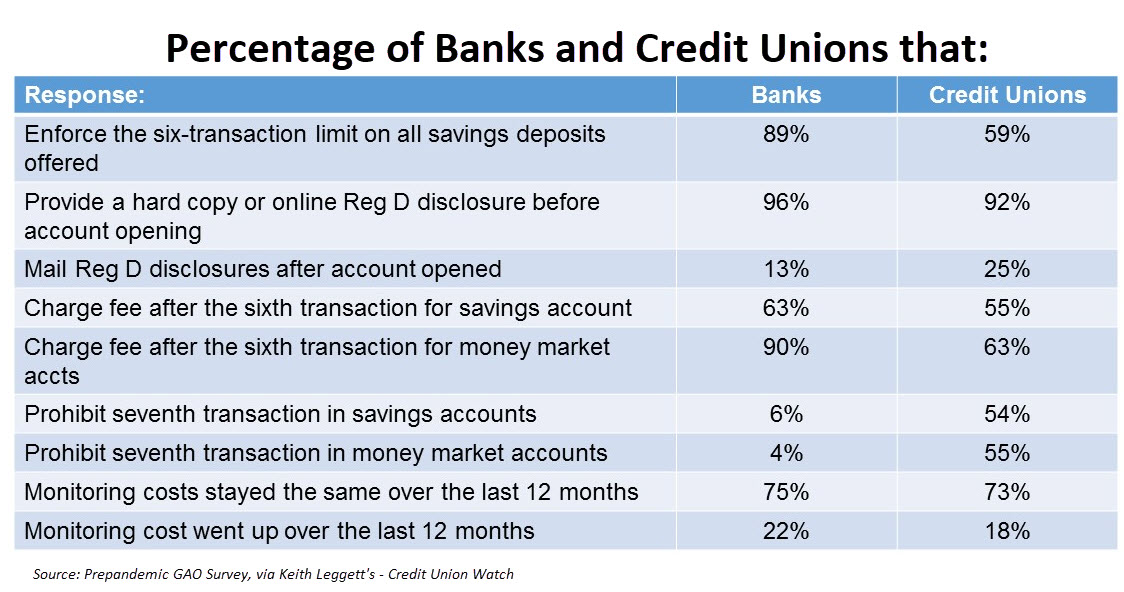

The Government Accountability Office did a study of more than 12,000 banks and credit unions before the pandemic and found the following:

The transaction limit was somewhat relaxed in 2009 and then, during the recent pandemic, was wisely suspended in April 2020 to allow greater access to emergency funds. Despite the change, many banks persisted either out of ignorance, strategy, or confusion.

The Current Status of the Six Transaction Limit

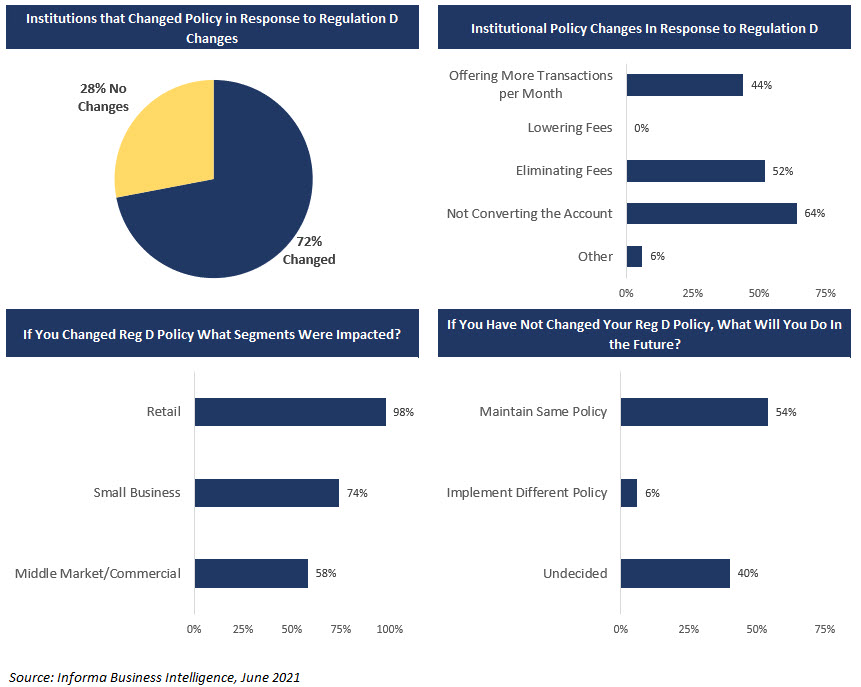

A survey last month by Informa’s Financial Intelligence Unit (below) showed that 72% of banks immediately changed their policies to allow customers more freedom. Most banks allowed unlimited transfers and withdrawals either by changing policies or removing any fees associated with overages. 44% of institutions increased the transaction limit, with nine or 12 transactions being the most common.

Interestingly, of the 28% of banks that still have not changed their policy, 37% are still considering changes, while 63% said they would not be making any changes.

Equally interesting, those banks that did relax their Reg D limits mostly did so related to their retail customers. Only 74% of those banks that did make changes also relaxed the limits for their small business commercial customers (ironically, the customer segment that needed the most help during the pandemic), and only 58% relaxed them for their middle-market commercial customers.

Despite the stoppage of the six transaction limit, for those banks that did allow a higher number or unlimited transfers, it is interesting to note that customer behavior barely changed. Maybe because of the surge in deposits from Stimulus and the lack of opportunity to spend during the pandemic, the customer did not need to tap their savings or money market accounts? Maybe it was a result that few banks advertised the change to their customers? Perhaps because we have trained our customers for so long to use their checking account for transactions, savings or money market account usage for transactions was never considered. Whatever the case, the data begs the question what do we do from here?

Strategic Question 1: Why Not Limit Transactions?

The original concept of limiting transactions from savings and money market accounts was to make these accounts less transactional. Banks often paid higher interest on these accounts, so the thinking went that banks would pay a higher interest rate in exchange for more stable funding.

The problem quickly arose that either the bank or customer had so many loopholes that these accounts were often as volatile as a checking account. It is ironic that many banks, in an effort to attract deposits during high-growth years (such as 2006), paid interest that was so high on their savings and money market account that it shortened the duration and decreased the account’s convexity to the point of training customers to be more interest-rate sensitive. In other words, banks used a policy that was designed to make them more stable and bastardize it to the point of making them less stable.

Conversely, many banks paid very little on their savings or money market accounts making these accounts unpopular.

The question now arises – should a bank keep its different classes of accounts tiered by purpose? The answer, of course, depends on the deposit strategy of the bank and its target customers. If you pay interest on your checking and business checking, then the point is probably moot. However, suppose your bank wants to go after longer-term deposits on a cost-effective basis proactively. In that case, intelligent bankers know the way to do that is in savings, in particular, as they can achieve deposit performance better than any other product in the bank. A well-structured savings account has a longer duration than most certificate of deposit structures while having a fraction of the cost of a checking account.

Creating a premier savings account as a person’s core account and then allowing easy or even automatic sweeping into a no-interest transaction account might be the way to structure your deposit base. A bank would eliminate its money market account in the process. This would maximize savings account performance, minimize operating costs while increasing customer satisfaction and engagement.

Conversely, you could train your customers, like most banks do now, and focus the checking/transaction account as a primary account and then allow an easy sweep into savings. This essentially does the same thing but often results in lower savings performance.

That said, in this era of low rates, it is tough to pay enough interest to make a difference to the customer while not increasing the interest rate sensitivity and hurting margins in the process. We would argue that no matter how you come out on this issue, it is probably the wrong time to execute a strategy but likely a good time to prepare a strategy.

Strategic Question 2: When are you going to get rid of your “checking” accounts?

The recent changes to Reg D now beg the question of – what is the difference between your checking accounts? Are you really pushing customers to move money from checking to savings or vice versa? Of course, before you answer this question, the first question to answer is what does your checking account looks like in the future?

As an industry, it is only a matter of time before we see the cessation of checks and the “checking account” becomes a “transactional account.” Some banks have already started the switch. In case you think this is more style over substance, consider that what you call your checking account is making more and more of a difference. In the future, we will present data that shows that when you have “checking” in the name of your demand deposit account, it results in higher acquisition costs. More importantly, by continuing using the name “checking,” we send a message to employees and others that checks are still important to the bank, which is increasingly far from the truth.

Strategic Question 3: Should you redo your account structure and capabilities?

The answer to this question is that, at a minimum, you should consider restructuring your deposit accounts. The majority of banks in this market sell interest checking, savings, and money markets, all paying about the same interest rate. In the process, these banks are getting no deposit-building value from these accounts. They are confusing the customer. They are increasing the cost of customer acquisition, and they have significantly higher operational costs stemming from having to maintain and manage multiple account types.

Consider for a second that it cost the average community bank around $1mm to maintain, report and manage their money market account structure. That is a lot of operational costs for little benefit. This is capital that could be used for the bottom line, to pay more on their savings accounts, or to go into product development.

Conversely, for banks that want to keep transaction limits in place, it pays to create additional barriers in the savings account and change the product to support higher savings rates. Instituting additional restrictions such as no withdrawals without penalties for a period of time or limiting the dollar amount that can be freely withdrawn would turn the savings account back into a true savings account.

In exchange for living with greater restrictions, the customer would gain a higher rate of interest. On the other hand, the bank would gain an account with a greater duration and better convexity so that the account drives greater value in up and down interest rate cycles.

What Does The Customer Want?

Of course, if you ask customers, which is precisely the place you should start to answer these questions, you will find out that what customers want is to have various deposit accounts that they can use for specific purposes. These “sub-accounts” are often used for saving for emergencies, college, retirement, vacations, a new building, or a variety of other reasons.

To meet this demand, some banks have either allowed the ability to create specific “goal-oriented” accounts or create an omnibus savings account that allows for the accounting of each sub-account. In this manner, the customer can create an unlimited number of specialty savings accounts without driving up the operational cost of the bank.

Banks could create a single interest-bearing transactional account that allows subaccounts. In the process, a bank could eliminate its savings and money market account. Then, it should start its certificate of deposit structure in Year Two, thereby increasing the duration and convexity of both the transactional account and of the CDs. Banks gain the best of all worlds in terms of operational efficiency, customer satisfaction, and deposit performance.

Putting This Into Action

The fall of transaction limits now allows both the checking and savings to be transactional. The fact that there has been very little change from both the product side of things and the customer behavior dimension screams inefficiencies in the system. Banks need to eliminate a layer of cost and consolidate account types or leverage account types to increase deposit performance. Either way, banks should be proactive and choose one in order to increase profitability.

The topic is timely, as managing your deposit base is likely one of the most profitable endeavors to build franchise value in a rising rate environment. Challenger banks like Chime, Varo, Current, MoneyLion, and others have and will continue to take market share on this very premise of making accounts simpler, cheaper, and more effective.