Are Commercial Loan Points Worth it for Borrowers?

Should borrowers pay commercial loan points to lower future interest payments? Loan or mortgage points are upfront fees paid by the borrower to the lender to reduce the interest rate on a loan or mortgage. For example, assume that a borrower is considering a loan, structured as a 25-year amortization, due in ten years, at 7.00% fixed rate. For this loan, the bank should be able to accept a $36k upfront fee to lower the payment on the loan by 50bps to 6.50%. The $36k fee is the present value of 50bps on the loan payment for ten years on a 25-year amortization. We see more borrowers asking about paying loan points on commercial loans, and a few decide to follow through with the strategy. We break the analysis down to help lenders advice borrowers and their bank.

Implications of Commercial Loan Points

For assorted reasons discussed below, loan points paid by borrowers are a major disadvantage to the borrower and major revenue driver for lenders. The reasoning is similar to the inverse argument that upfront fees to the lender are a major source of profitability (more on that subject here and here). In a broad sense, loan points represent nothing more than the present value of future interest payments, therefore, if properly calculated, the lender and borrower should be indifferent between cost/revenue whether upfront or over time. However, the reality is more complicated. There are three major drivers that make loan points not an equivalent outcome for borrowers – taxes, liquidity, and loan prepayments.

Taxes

Loan points on commercial loans may or may not be tax deductible depending on jurisdiction, entity status, and the magnitude of the points (we urge borrowers to obtain their own independent and qualified accounting advice). However, if loan points are not tax deductible in the period paid, then paying loan points represents a major disadvantage to the borrower – because the borrower pays the present value (larger amount) and receives the tax benefit over time (smaller amount) and the present value calculation for the loan points is not incorporating this difference. If loan points can be deducted in the period paid, then the borrower might gain an advantage in paying points upfront versus paying higher interest over time. However, if the borrower believes that tax rates will decline in the future, then paying loan points is an advantage to the borrower who may deduct the larger loan points in the period paid versus the lower interest deduction over time. Forecasting future tax rates is even more uncertain than forecasting future interest rates. There might be idiosyncratic reasons where entities are advantaged to pay points upfront for tax purposes – but we have rarely seen such a scenario in practice.

Liquidity

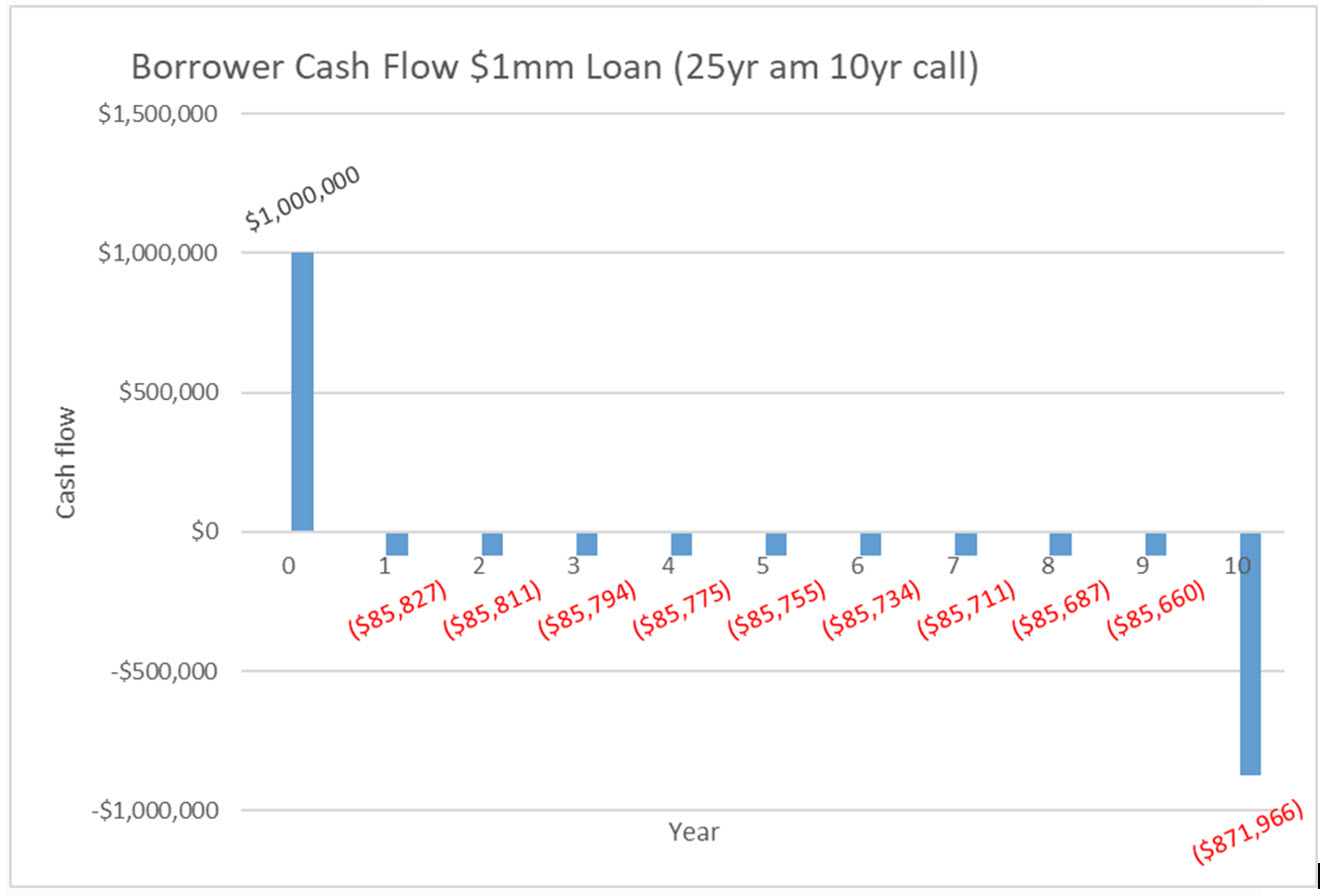

Paying points is a major liquidity disadvantage to borrowers. Every loan point dollar paid by the borrower represents a dollar loss in loan proceeds. The borrower would be better off reducing the loan size by the number of points paid, or better still, holding the liquidity to apply to future payments in the event of cash flow challenges. Let us examine our example loan – $1mm, 25 amortization due in ten years, at 7.00% fixed rate. The loan profile is shown in the graph below. The borrower obtains $1mm in loan proceeds and pays 7.00% per annum interest and principal and owes the remaining balance at the end of the contractual term.

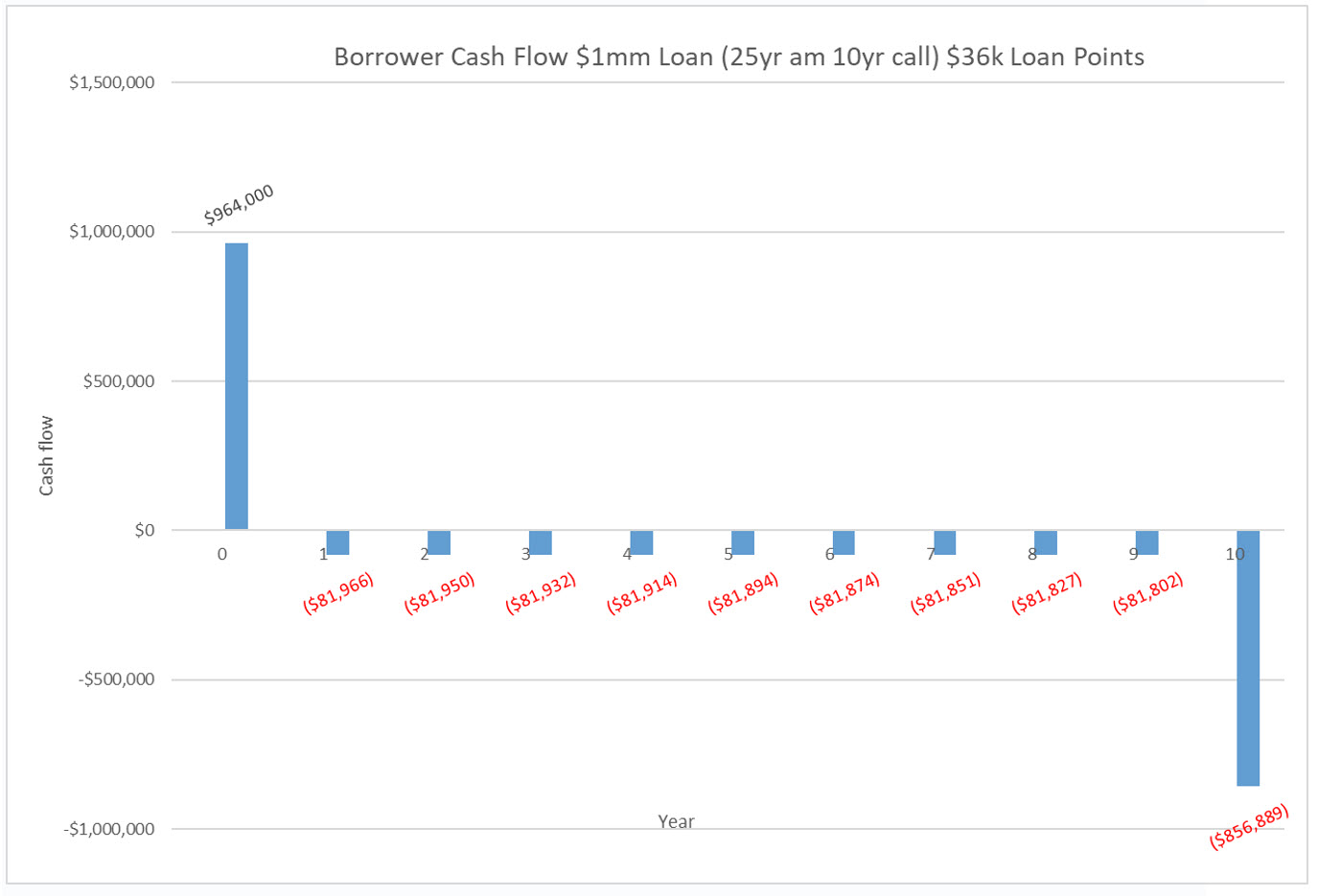

That same loan with a $36k loan point payment (equal to a 50bps interest reduction) is shown in the graph below. While the borrower has lowered annual interest payments, and the balloon payment, the loan proceeds are reduced by $36k. The borrower paid $49k less in interest on the loan over the 10-year period (representing the present value of $34k, with some principal adjustments), but the borrower is not advantaged in any way. The borrower would be in the same position (with more upfront liquidity) by choosing a $1mm loan at 7.00% and not paying the points.

Prepayment

Loan prepayments is the wedge that drives the bargain between the lender and borrower. Typically, loan points are not recouped if the borrower pays down the loan or prepays the entire loan before the contractual term (some hedged loans are an exception to this). The math makes loan points a considerable revenue driver for lenders and a serious disadvantage for borrowers. Assume that our example loan is prepaid in full at the end of the seventh year. The borrower effectively lost the benefit of the last three years of the loan points, which is the prevent value of about $9k (out of a total payment of $36k). If the same loan prepays in full at the end of the fifth year, the borrower will lose about $15k of the loan points. Similar disadvantages accrue to the borrower for partial early prepayments along the ten-year life of the loan. Each dollar loss to the borrower resulting from early loan prepayments result in the equivalent additional income to the lender.

Conclusion

The concept of net present value of loan points or loan fees aims to make creditors and debtors indifferent to when payments are received. In theory this concept is sound and equitable, but practical applications can skew results to the benefit of one of the two parties. For the same reason that we plead with bankers to maximize fee income, when possible, we also advise our borrowers that paying loan points is, typically, a bad choice for their P&L. We also see lenders that function as trusted advisors to borrowers suggest that their customers avoid loan points whenever possible.