How to Best Use Volatility Instruments In Banking – Part II

Last week we discussed how lenders might use swaps, caps, floors, and collars to help borrowers manage borrowing costs. We outlined how the market values swaps and volatility instruments (like caps and floors), and we reviewed the fundamental reasons for how and why these hedging instruments are applied to commercial loans. In this article, we will provide some guidance that lenders may apply to position, price, and compare swaps, caps, floors, and collars for their borrowers. We will also compare the relative value of swaps, caps, floors, and collars.

Swaps vs. Volatility Instruments

While a swap is priced on the market’s current expectation of future interest rates, volatility hedges are priced on expected future interest rates and on the variability around that expectation. As outlined in the last blog, caps and floors have an intrinsic and time value. Informed borrowers do not buy caps for the intrinsic value but for the time value. This creates some interesting and nuanced differences between swaps and caps and floors (the combination of a cap and floor is a collar).

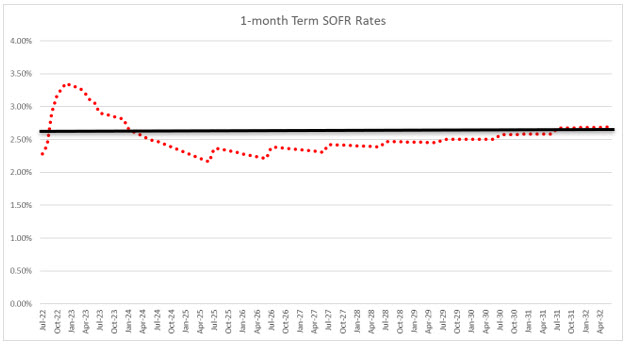

Borrowers purchase a swap to eliminate any variability in loan payments. The significant advantage of a swap is that borrowers do not pay an upfront fee to buy this protection. The graph below shows the market’s current expectation of 1-month term SOFR in the dotted red line for the next ten years, and the average of those dots is the swap rate as represented by the black line. By buying the swap, the borrower exchanges all future and unknown variable rates for the known swap rate.

Borrowers buy swaps for various reasons, including the belief that the market is underestimating future short-term rates, or they are required by the lender to protect a minimum debt coverage ratio, or because of the flexibility that a swap provides for future debt needs. However, the most common reason borrowers purchase swaps is to avoid the possibility of paying a higher rate in the future – a simple risk mitigation tool driven by fear of unknown future interest rates. Borrowers are also averse to paying fees associated with volatility instruments.

Advantages of Volatility Instruments

Aside from some very sophisticated entities that buy caps because they believe that the market undervalues future interest rate volatility, most commercial borrowers buy caps as an insurance policy they hope never to use. A borrower is always economically better if the cap expires without ever paying a settlement. The borrower’s debt cost is always lower if interest rates do not reach the cap strike level.

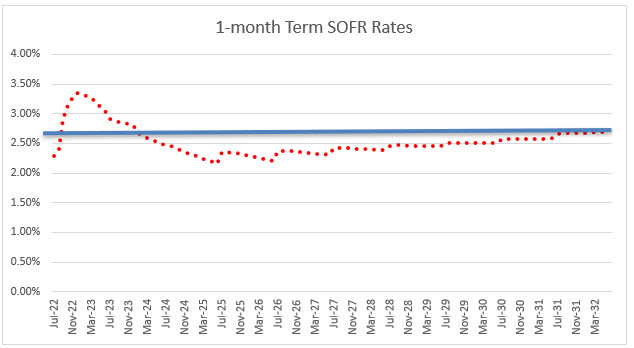

Borrowers can decide on the cap level suitable for their business needs, but it makes no economic sense to buy volatility instruments for their intrinsic value. Instead, caps are purchased for their time value. The graph below shows a cap strike level (the blue line) that is below the market’s current expectation of one-month term SOFR for a portion of the next ten years. There is no economic advantage for the borrower to purchase intrinsic cap value because the higher cost of the cap is already factored in the payout to the cap holder.

Borrowers who have a view on the future path of interest rates, or especially have a different volatility view from the market, purchase caps as catastrophic insurance policies and set cap rates high enough to cheapen the cost of the cap but still retain some level of interest rate protection. These purchasers fully expect the cap to expire without any payout – which is the best outcome for the borrower.

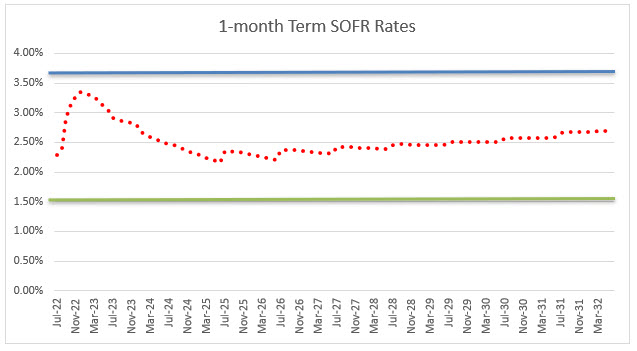

The above concepts apply to other volatility products, such as floors. However, borrowers use floors to finance a portion of the cap cost. Borrowers buy a cap and sell a floor, known as a collar, to reduce or eliminate the cost of a cap. The graph below shows an out-of-the-money cap in the blue line and an out-of-the-money floor in the green line. The borrower using a collar has a floating rate loan between the floor and the cap rates.

Disadvantages of Caps

Caps must be purchased with a fee, and most borrowers are averse to out-of-pocket fees. The cost of caps is surprisingly high – in today’s market, a cap struck at 1.00% over the swap rate for 10 years, has a cost of 40bps higher loan rate to the borrower, and this is before any transaction costs (profit for the cap seller). Further, cap costs become exceedingly high for instruments beyond 10 years because the market is illiquid past that term. The transaction costs for caps become especially expensive for loans under $5mm in size. Finally, the documentation for a cap may be simple, but the value of the cap upon early termination cannot be defined in a document, and borrowers must trust the bank for any remaining cap value upon early termination.

Borrower Motivation For Collars vs. Swaps

Swaps can be in or out of the money for borrowers depending on interest rate movements from the time the swap was contracted to the time it is terminated. Borrowers that believe interest rates will fall in the future are not natural swap users because it will cost the borrower money to terminate the swap prior to maturity. On the other hand, borrowers that believe interest rates will rise in the future are more likely to use swaps because they may receive a fee to terminate the swap prior to maturity.

Why would a borrower use a collar instead of a swap? The average borrower is unable to predict the future path of interest rates and much less be able to predict future volatility of interest rates which dictate the value of caps and floors. Most borrowers inquiring about caps want to eliminate a prepayment scenario associated with a swap, but when they learn about the cap fee, they often turn their attention to collars in an attempt to lower the cap fee. However, a collar has a prepayment scenario – if interest rates fall, the floor becomes valuable, and the cap becomes worthless, resulting in a prepayment fee owed by the borrower. That prepayment fee is difficult to calculate upfront and cannot be easily communicated or documented.

To offset the cost of the cap fee, the borrower sells the bank a floor, and there are many ways to make the collar zero-cost to the borrower. While there are many ways of creating a zero-cost collar, there is one zero-cost collar structure that tends to be best for borrowers who do not have a volatility view that is different from the market’s view. That collar is where the cap and floor are struck at the same level – the borrower does not pay if rates go above that level, and the borrower does not get the benefit if rates fall below that same level. That structure is also known as a swap. A swap is the composition of a floor and cap at the same level, and payouts and prepayment scenarios are identical between a swap and the floor and cap struck at the same level.

Conclusion

The vast majority of the borrower market prefers swaps because there is no out-of-pocket fee for a swap. Since borrowers that use hedging instruments cannot out-predict the market for rates and volatility, caps and floors lose much of their advantage. Interestingly, when borrowers are given the choice of structuring a zero-cost collar for a loan, many prefer the cap strike to be as low as possible, and the floor is then raised to reduce the cost of the cap to zero. Invariable, these same borrowers arrive at a cap and floor struck at the same level – which is known as a swap.