How To Sell Prepayment Provisions In Commercial Loans

If banking had an Olympics, creating loan value would be an event. The recent Fed meeting, with its hawkish tone, makes the sport of loan value creation even more important. While many lenders are good at gathering new business, they may lack the experience to create optimal mutual value. To make it into the podium, bankers must not only understand how to work with structural components but how to position them for the most efficient application of the creation of value. In this article, we focus on prepayment provisions and look at how a past gold medal winner does it.

Prepayment Provisions Not Penalties

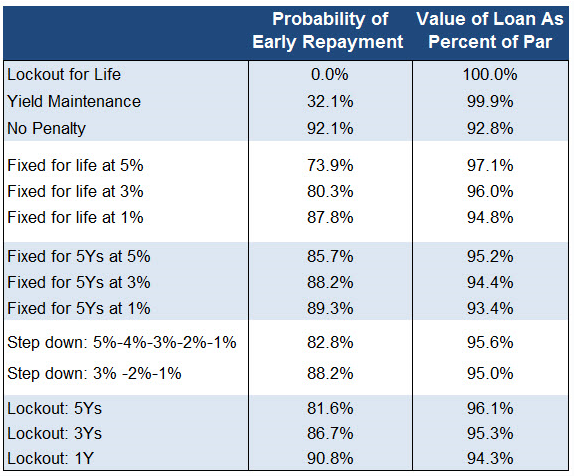

In a competitive market for commercial loans, every feature that can preserve credit quality or maintain pricing can be valuable to the lender. One element that many commercial banks attempt to differentiate with borrowers is the prepayment provision (or sometimes the lack of one). Many community banks will market their fixed rate loans based on the simplicity of the prepayment provision, and this starts by understanding the value that each provision creates. This can be summed up by the table below that looks at the probability of repayment and the net value of a ten-year commercial loan over up, down, and flat interest rate cycles:

As you can see, some prepay structures create more value than others. A lockout for the life of the loan is a provision where the borrower cannot repay without satisfying all the interest is at one side of the spectrum, while a loan with no repayment provisions is on the other. No prepayment provision gives the borrower a free option and almost guarantees (92.1% probability) that the borrower will repay early.

Another way to look at this is that a loan without a prepayment provision is only worth 92.1 cents on the dollar due to the probability of early repayment.

Of all the options, the declining balance prepayment provision is the most used. Here, we will focus on the structure where the borrower’s prepayment charge will equal 5,4,3,2 or 1 percent of the loan balance for years 1 through 5 of the loan. This is by far the most common provision. To better learn how to position against it, we asked one of the top-performing lenders from a national bank how they sell against the declining balance prepayment provision. We want to share his strategy so that community banks can manage their marketing more effectively.

Step 1: There is No Prepayment Penalty on the Loan

First, when positioning a loan to a potential borrower, the Banker tells us that he always starts out with a loan with no prepayment provision, or penalty. The representative describes the loan as prepayable at any time without a cost or a fee. However, the Banker also indicates that the loan will be a floating rate only structure and that the loan will come with slightly higher fees/interest rates because the borrower has complete freedom to refinance. The reality is that since the Bank gives the borrower the complete option to refinance, this is the riskiest and least profitable loan a bank can make. The greater the volatility, the greater the probability of losing this loan in the future.

Alternatively. the Banker also explains that the borrower may be best served by a fixed-rate loan if the borrower has a long-term need for the debt capital and/or believes rates are going up.

If the borrower does want a fixed rate, then the loan can be “tailored” (a word used several times in the presentation) to the customer’s specific needs. The loan can be fixed up to the commitment term of the credit based on the borrower’s cash flow requirements and interest rate views.

Step 2: Align Interest Rate View

The Banker goes on to explain if the borrower’s view is long and they have a view that rates will head higher, then the recommendation is for something called a “symmetrical prepayment provision,” also known as “yield maintenance” or a “make-whole provision.” It requires the borrower to pay a fee at the time of prepayment if rates are lower; however, the borrower will receive a fee at the time of prepayment if rates are higher.

Here, the Banker is selling into two emotions. First, greed that if rates are higher, there will be a prepayment fee paid to the borrower. Second, fairness. The Banker explains that the symmetrical nature of yield maintenance is “fair” as it can benefit the borrower if rates move up just the same way if rates move down. This sense of equality is a powerful psychological trigger and helps the borrower understand the loan from the bank’s position.

The Banker then quickly asks the question: “Where do you think interest rates may be in the future?” Any borrower who expects rates to be higher is a good candidate for this bank’s fixed-rate product, and any borrower who expects rates to be lower or to remain the same is a candidate for the bank’s floating-rate loan structure. With either view, the bank has a product to sell and the conversation is over structure, not price.

Step 3: Setting Term and Amortization

The Banker then wants to set the amortization and term to best meet the borrower’s view and cash flow. The bank wants the longest set of cash flows possible. This not only increases the present value of the loan but retains the borrower for a longer period of time thereby increasing their customer lifetime value. The borrower, on the other hand, wants the shortest loan possible so long as they have sufficient cash flow to handle the debt service and provide enough capital for both operations and growth. Usually, this also means a longer-term loan.

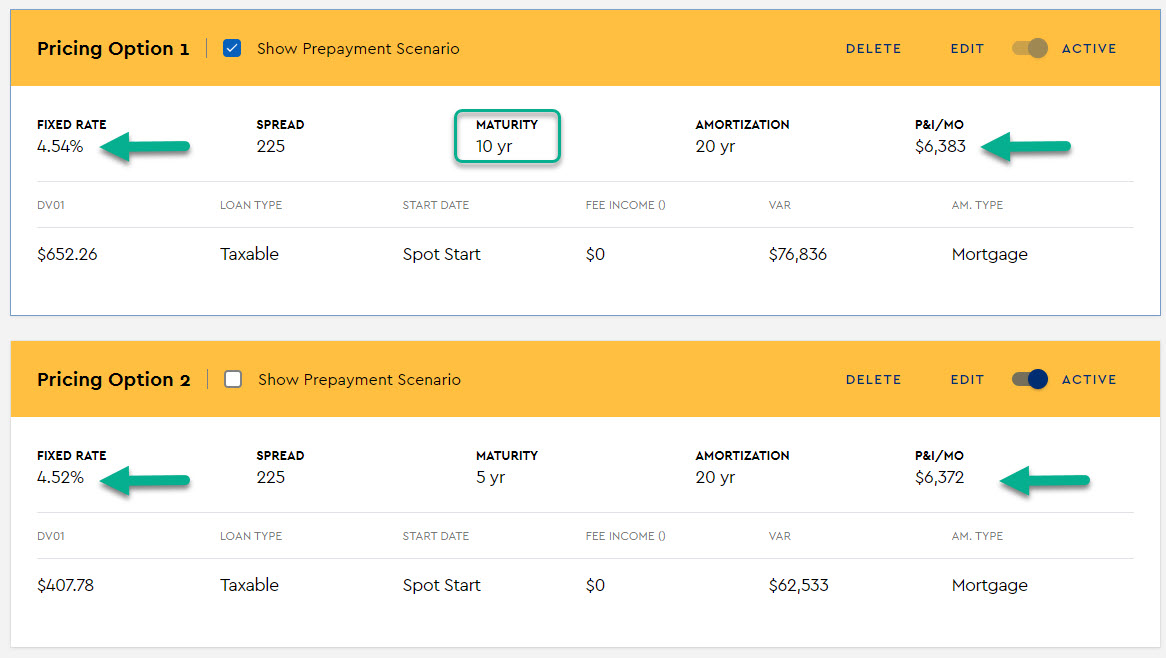

Given the flatness of the yield curve after the March FOMC meeting, the rate difference on a ten-year loan compared to a five-year loan is only two basis points (below). More importantly, the payment difference is only $11 per month for ten years of interest rate protection and stability.

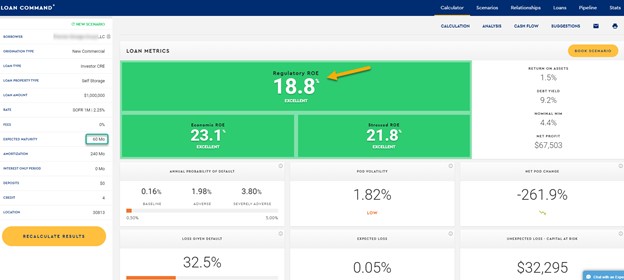

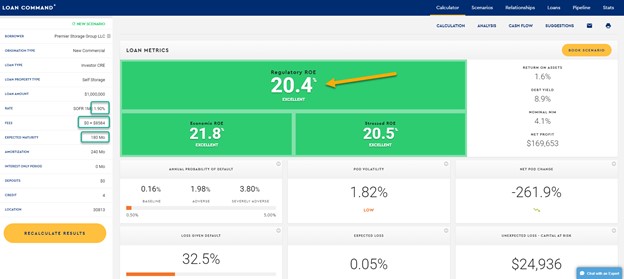

The Banker would put these and other options in front of the borrower to allow them to make the best decision. That said, since the 10-year loan has twice the cash flow, it’s a much more valuable loan (below). Here the Banker tightens the spread by some 35 basis points further saving the borrower money and dropping the 10-year fixed rate BELOW the five-year rate. Since the bank doesn’t want ten-year interest rate risk, it also hedges the loan and collects a fee (More information HERE).

The net result is that the bank increases the ROE above a risk-adjusted 20% while the borrower enjoys the stability and lower cost of the ten-year loan. It is important to note that at a 1.90% credit spread, the borrower now saves almost $200 per month per one million of the loan amount. This not only reduces the cost to the borrower but also reduces the credit risk to the bank since the rate is more stable AND there is higher debt service coverage.

Step 4: Transferring the Economics in The Future Using A Prepayment Provision

The most impressive part of the sales pitch is how the Banker explains to the borrower that they should lock in rates for as long as possible given today’s low-interest-rate environment and use that financing for any future borrowing needs. The explanation states that not only can the borrower enjoy the low rate for the existing loan, but the low rate can be transferred from one loan to another if the loan stays with the bank. For example, if the borrower wants to finance another property or amend the loan to include additional loan commitments, the current low rate can be preserved without prepayment (and tax) consequences for any future use if the bank can underwrite and approve the credit in the future. The Banker points out to the borrower that the loan can be transferred among any of the borrower’s properties, and the rate stays unchanged.

Step 5: Comparing Prepayment Provisions and Rate Movement

Finally, the Banker lets the borrower know what could happen with a yield maintenance provisions if rates go up or down. The Banker puts the table in front of the borrower and not only shows the borrower the near-symmetrical (it is not perfectly symmetrical because of the upfront fee income) nature of the provision but also shows what happens if rates go down (the left side) and the borrower might have to come out of pocket, or rates go up (the right side) and the borrower receives an additional fee or can roll the profit over to a new, amended facility.

At this time, the Banker compares these scenarios to the prepayment penalties that other banks are offering. The Banker can take any scenario the borrower can come up with and walk through the math.

For example, if the borrower believes interest rates are generally heading higher, the symmetrical prepayment provision offers safer and more advantageous prepayment economics for the borrower. Interest rates would have to fall almost to zero across the entire interest rate curve for the borrower to experience a higher prepayment cost over the next five years with symmetrical prepayment than with the common 5,4,3,2,1 declining balance penalty.

Putting This Into Action

Community bank commercial lenders need to know what they are selling against and how to effectively position their loan structures. While the above example was the sales technique from a very successful lender at a national bank, we have seen similar sales pitches from Bank of America, BB&T, Fifth Third, Regions Bank, PNC, US Bank, Truist, and other national and regional banks.

We believe that to succeed against national banks, in some circumstances, community banks must present an alternative to the declining balance prepayment provision. In an anticipated rising interest rate environment, the simplicity of a declining balance prepayment provision does not offset the downside risk to the borrower, and an alternative prepayment provision may make more sense.

Increasing lender training around the area of loan structuring helps lenders better compete in today’s competitive marketplace. Having a thorough understanding of prepayment provisions is the cornerstone to being able to create value for both the bank and borrower. If lenders are able to do that, they will find that they will also create value for their career as the ability will help position the lender as a clear trusted advisor. Lenders who can position themselves as such may find themselves in medal contention, should there ever be a banking Olympics.