7 Rules to Help You Decide When To Start a New Bank Product

After talking about the role of bank product managers (HERE), many bankers and bank board members asked the question – How do you know when to start a new product? This article covers seven rules that form our framework for when banks should consider either building or buying a new product. The Rules will help inform your bank on when they should launch a new product and what priority that product should have. Working through these rules not only helps your bank achieve a greater level of success when launching a new product but helps ensure you have a transparent process that increases the probability that you will even TRY to launch a new product. If you want to become a more innovative bank, review our seven rules to see if you can pick up some ideas to improve your current methodology.

Rule #1: Solve a Customer Problem

Are you introducing a new product just because it is available? Often banks tend to roll out a new product because it is easy or trendy. Crypto is the latest example. Does your customer base have a problem storing cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, and do they want a checking account based on that? Maybe. However, any time you want to roll out a new product and THEN find a customer base, know that these are two significant efforts the increase your likelihood of failure. Starting with solving an existing problem your current customer base has is usually your best path towards new product success.

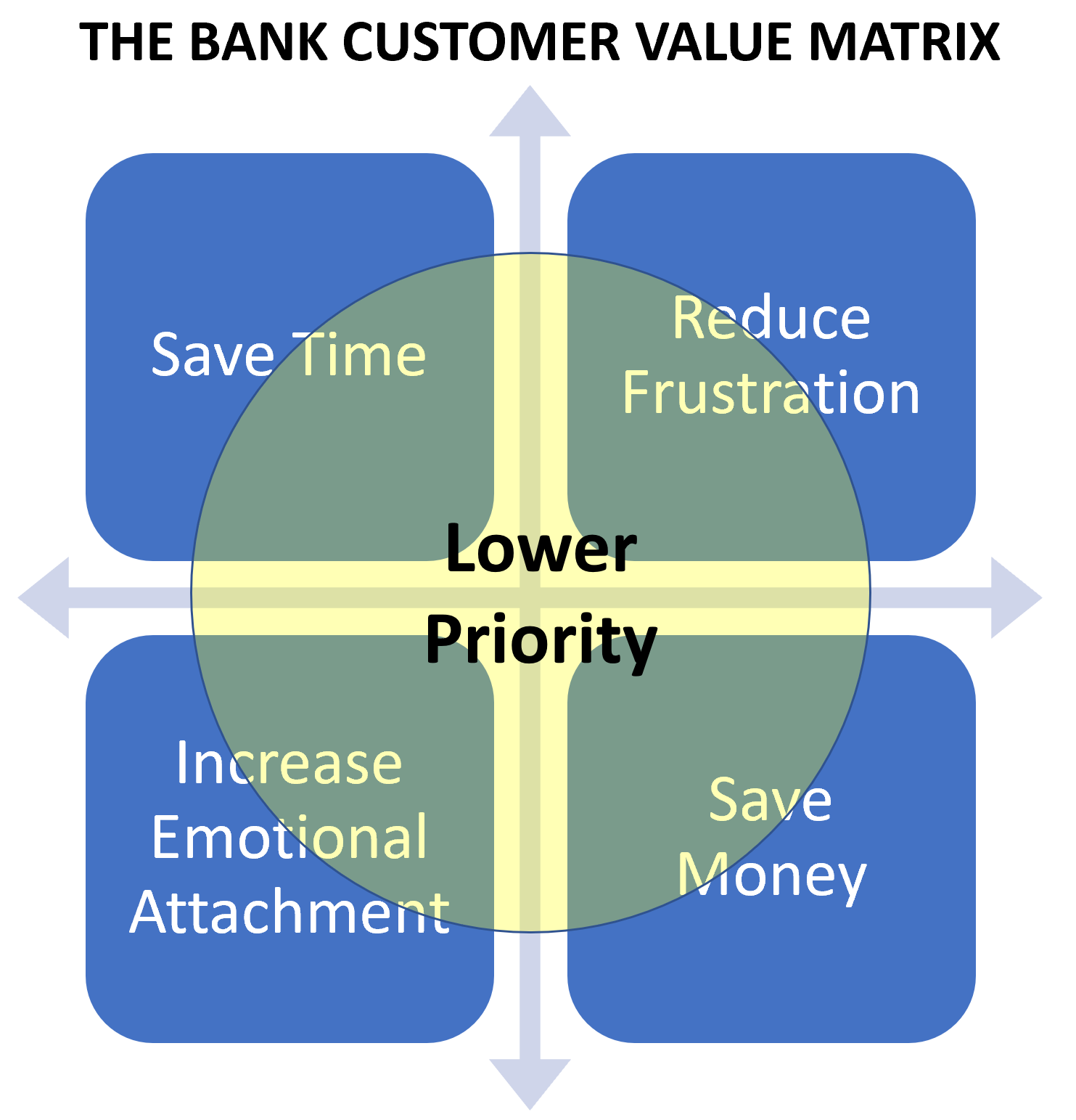

Using the “Customer Value Matrix” above, we try to quantify and chart the value of any potential new product to the customer along four dimensions: does it save the customer time; does it save the customer money, does it reduce some frustration that the customer is having; and, does it help the customer feel better about themselves while creating an emotional attachment with the bank’s brand.

The concept with the Matrix is that you want to move as many points within each quadrant outside of the Lower Priority circle. The more points outside the circle, the more important the product is to the customer, and therefore the bank.

Rule #2: How much cost does it take out of the system?

While understanding projected profit is often difficult, understanding the cost savings of a new project is usually easier. By prototyping a new product or seeing a similar product in action at another firm, product managers can understand the required resources for a new product and compare them to the process today. The larger the savings, the higher the priority of the new product should have.

Often, community banks will set a clear dollar threshold for new products letting everyone know the hurdle they should strive for before suggesting a new product. For example, the “$1mm Rule” says you need to produce $1mm per year in revenue or save $1mm a year over five years to get a green light on a project. While crude and needs to be size adjusted for your institution, a rule like this is extremely helpful to communicate initial expectations.

As a side note, it is instructive for bankers to not only know the new product’s contribution to overall revenue, profit, and cost savings but know this information on a unit cost level. Calculating unit cost forces bankers to think through the myriad of issues associated with funds transfer pricing certain allocations like risk, marketing, compliance, and oversight. For any given product, it is critical to be clear on what are the fixed costs and what are the variable costs. This will give product managers a better feel for scale and required resources in good times and bad.

Rule #3: Does it Further Your Bank’s Strategic Goals?

Every product should support at least one pillar of your institution’s strategic vision and hopefully multiple pillars. A bank’s purpose is supported by its strategy, which in turn is supported by its products, customers, and people. The bank’s board and management should constantly monitor how well the bank’s daily actions support the achievement of this strategy, and that essentially starts with the products it has.

A famous 2013 internal report at Barclays Bank revealed how its culture and products “favored transactions over relationships, the short-term over sustainability and financial gain over business purpose.” The conclusion was that it was the bank’s misalignment of strategy that helped contribute to the environment of “reckless and risky employee behavior” that contributed to the bank’s poor performance during the financial crisis. While the bank’s strategic purpose was to help their clients grow and achieve their dreams, their products were primarily only focused on making the bank money.

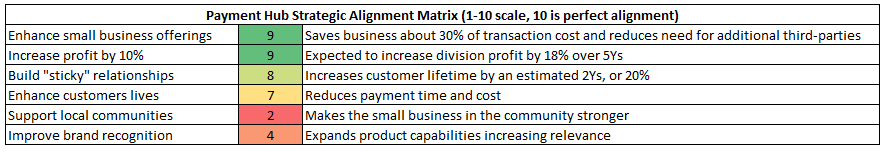

To help determine alignment, often an “alignment matrix” is helpful (below) that allows the semi-quantification along each strategic direction as either determined by a project committee, new products committee, or product manager (and then reviewed by executive management).

Rule #4: Is the product 3x better than the competition or 2x better than what you currently offer?

If you are a start-up in Silicon Valley, the mantra is that you must produce a product that is 10x better than what is on the market now before you launch a company around it. This is a little bit of hyperbole as you are never going to be 10x better than Amazon when it comes to e-commerce. Plus, a start-up contains a lot of risks as the entire company is often built around a single product. For a bank, the risk threshold is much less, so the improvement hurdle is lower.

That said, a bank product that is 25% better than what you have now may not be worth it. However, if the product is twice as good for both the bank and the customer, then it should be considered. Alternatively, if you don’t offer the product now, then the thought is it must be at least 3x better than the competition to motivate the customer to switch.

Rule #5: Does it push the bank into new technology or infrastructure so it can learn?

Certain products and business lines are “profit ready” from the start. They take time to figure it out. A new product may give the bank an entry point from which to learn and build. Cryptocurrency, for example, may prepare a bank to get ready for a central bank-issued U.S. Dollar. Offering identity-as-a-service to its commercial customers may push the bank into offering more products around banking-as-a-service. Other popular examples include voice banking, augmented reality, and internet-of-things banking,

Not every product is going to make a profit from the start, and not every product is going to save the bank a ton of money. For that matter, in the Steve Jobs tradition, sometimes the customer doesn’t know what they want, so Rule #1 may not apply.

Rule #6: Does the product take advantage of a new frontier?

This is a derivation of Rule #5 but goes beyond new banking technologies such as real-time payments and virtual reality. Here, as a result of technology or as a result of legal/regulatory changes, new markets may be opening up. A bank may want to launch a specialty group to finance robotic projects, legalized marijuana, or self-driving cars for fleets. There are certain “mega-trends” that are so big and so encompassing that innovative banks will find ways to put these tailwinds behind them to derisk any new project. Taking advantage of mega-trends such as 5G, AI, cyberthreats, sustainability, or biotechnology are all critical for consideration.

In addition to looking at products that fit first-order ideas, such as taking advantage of edge computing structures to help merchants process payment transactions in real-time, second-order ideas could also work. For example, remote work necessitated the rise of Zoom calls, but now Zoom-like calls are being used for e-commerce when it comes to industries like fashion and electronics. It is only a matter of time before a bank embeds its payment capabilities into these new video sales and event calls to facilitate real-time payments.

With the rise of digital banking, as geography becomes less important, many community banks will utilize the opening of new markets to pivot to a regional or national footprint and redefine “community” using industry, not geographical ties.

Whenever venturing into a new frontier, it is important for a bank to ask themselves if the customer base ready to accept the new product? Does the customer base have the needed technology such as bandwidth, and is the culture base willing to socially accept the product? Often a product is technically feasible but can’t happen until a more significant percentage of the customer base is prepared to get the product. This is currently the case with cryptocurrency, as more banks are waiting for wider social acceptance.

Rule #7: The new product must not have other constraints that limit the new product’s success.

This Rule stems from Eli Goldratt’s famous Theory of Constraints that basically says any new process is only as fast as its slowest constraint. Digitizing consumer lending may be a great idea, but it would be a total waste if you have not improved how quickly you can get new customers approved through compliance. Banks need to ensure that any new product is not going to be slowed down by risk, servicing, sales, marketing, or management.

Putting This Into Action

Developing a process for creating new products makes success more probable with each product launch and makes new products more feasible as it provides a roadmap to follow. To become a more innovative bank, it is important to have a successful process for new product development in place as banks rarely rise to the level of their key performance indicators but call to the level of their process. A good process makes for good products.

Hopefully, our seven rules provide a framework for helping your bank determine when to build or buy a new product to launch.